In Valley Hill, North Carolina, 20 miles outside of Asheville, Will and Wes Wienman have quietly but quickly carved out a niche as highly respected mandolin builders. Referring to their sound and process as “Vintage by Design,” the first mandolin to leave the confines of their home shop made it into the hands of Jarrod Walker, mandolinist for Billy Strings, and they’ve been off to the races ever since.

The Wienmans’ music history goes back to the 1970s, when Will Wienman’s fascination with violins got him started as a violin dealer and repairman after college. Annual trips to the largest violin auctions in the country introduced him to a wide variety of violins. At the same time, he was learning about and acquiring mandolins, mandocellos, pre-war guitars and all manner of history’s best offerings from Gibson and Martin, as well as then-new-on-the-scene builders like Gilchrist. In the early 1980s, when his son Wes was an infant, Will acquired a 1924 Gibson Loar F-5—an early version with the fern headstock inlay—that would make its way into George Gruhn and Walter Carter’s Acoustic Guitars and Other Fretted Instruments. Though he eventually sold the Loar, Will always maintained an interest in the voice and construction of mandolins.

The idea of building professional-level mandolins had been in the back of Will Wienman’s mind for decades, ever since building his first mandolin in the late 1970s. He knew he’d need help, because he doesn’t believe he has all the attributes he considers required to turn out the master-quality instruments he envisioned (almost infinite patience, steady hands, the ability to spend countless hours in the shop day in and day out). Regardless, he was bitten by the bug and continued studying and experimenting with instrument sound, primarily by re-graduating, voicing and fitting bass bars inside over 100 violins. He even built a mandolin that had an easily removable top so he could change one aspect of the instrument at a time and observe the results. He also started buying high-end spruce and maple in the early 2000s, knowing that one day he’d find the partner who could bring to life the sound and design Will envisioned. At the time, Wes was a teenager with little interest in building mandolins.

Fast-forward to 2014, and Will had relocated to western North Carolina, living on his own in a house with a workshop, lots of tools and lots of aged tonewoods. Wes was in his early 30s and living in Florida, but he was open to a change of scene. The two began exploring the idea of making mandolins, and soon Wes joined his dad in North Carolina.

Will and Wes have fairly different personalities yet complementary skills, which is apparent when they are interviewed together. It becomes clear that their partnership building mandolins is about more than familial convenience. Speaking to Wes, Will notes Wes was always “fascinated by sound.”

“Let’s be honest—you turn your own drum edges. You shape your own piano felts. You mod your own microphones.”

Wes began to think about his own skills and dispositions: “People have to do things for a living, but it turns out I was fired from every desk job I ever had.” He nonetheless realized that he has a deep capacity for focusing on one thing for long stretches of time—the kind of patience required for building carved instruments. “You can’t be in a hurry. You can’t get mad at inanimate objects.”

Will agrees. “His ears are really good. His hands are really steady. He’s really good with numbers, he can envision the geometry of 3-D shapes, and he’s really meticulous. And he’s absolutely relaxed about going slow and getting things right. And that’s what it takes to build a mandolin. If you’re going to build something really good, you just gotta be willing to stick with it.” Some of those things are likely natural gifts. And some are probably the product of osmosis from growing up in a household with a violin dealer and instrument repairman.

Regardless, with more than a hint of sarcasm, Wes responds, “So I figured, what better to do in my mid-30s than move up here and move in with my dad?”

Building Mandolins

The Wienmans’ workshop is full of the usual tools (many hand-made to accomplish specific tasks), dehumidifiers, jigs and raw materials that high-end luthiers are expected to have. But there is also a sizeable collection of files and pictures and historical materials about artisan-made instruments. Plaster casts of early 20th-century Gibsons. Graduation maps and technical drawings of several Loar mandolins. Tracings of various holy grail instruments. Files full of notes about world-class mandolins from the Loar era to the present. A perfect lab for Wes and Will to begin the inductive process of designing and building modern instruments inspired by vintage tone. There’s a reason the Wienmans call their mandolins “Vintage by Design.”

While Wes honed his artisanal skills, Will was involved in the big picture: “I knew how the tops should be graduated, how to get the tone bars to fit, what kinds of wood to use, how to tune the wood to itself…and the finish.” Basically “how to know when the wood wants to speak.” Wes likens those first years that he was in the shop to an anecdote in Ravi Shankar’s book about playing sitar: “He was recounting how he learned, and the first thing they would make you do is learn to sit in a lotus position for like a year, before they even put a sitar in your hands.” The first two years or so were dedicated to planning and design and good old trial and error. After a while, “we thought that, once we spent this much time doing it, we might as well spend even more time doing it, just to see it through. I knew it could be done. I knew we could do it. I just knew it.”

Spending time with the Wienmans, it is evident that this is much more than a business venture. Their partnership is fundamentally existential and based on intuition, rather than based on a business plan designed by an MBA. They didn’t start doing this to provide something no other builder was doing, or to take advantage of a market inefficiency or opportunity. Instead, Will says, “I know how it feels to have an instrument that just inspires you. I know what it is like to have an instrument in your hands that will do whatever you ask it to, whenever you ask it to—one that, when you play it, you find yourself doing things you didn’t even know you could do. That was my vision and my passion, and I knew we could do that.”

The Loar Mystique

One model of mandolin looms large over any builder of high-end mandolins primarily used for bluegrass: the F-5 model designed by Gibson, and more specifically, the 250 or so F-5 mandolins built under the oversight of Lloyd Loar in the early 1920s. Advertisements and forums and review videos are replete with strong opinions about how similar a particular modern mandolin may be to these mythic forebears. As for the Wienmans, while the majority of their mandolins built to date are heavily influenced by and in the Florentine F-5 style of the 1920s, there is a lot of nuance to how they think about the influence of Loar mandolins on their process.

“I’ve owned a ’24 Loar and have been studying them since about 1978,” says Will. And along the way he had friends with several Loars that he had the opportunity to measure and examine closely. Comparing these Loars side by side (and more since), Will was astounded how different they can be instrument to instrument—not only in voice, but also in construction. “I’m seeing these minor differences in the graduation of tops, side depth, break angle, neck shape and the arching of the back from Loar to Loar.” The real eye-opener for Will was when he had the opportunity to study six Loars at the same time: “They all had something special, but they were all a little different.” Accordingly, you’ll never hear the Wienmans say their mandolins are “built to Loar spec” (though that won’t keep you from finding the occasional aftermarket listing of a Wienman that describes it that way…).

“If you want to build an instrument that responds like a 100-year-old instrument within just a few years, you can’t build it like it was built 100 years ago,” says Will. This has led Will and Wes to slightly deviate from some of the most general Loar specs: The plane of the arching is different, the break angle and the way the neck attaches are different, the necks tend to be thicker and less v-shaped, and they tend to carve tops so that the symmetry of the graduations are different than those observed in many Loars.

“In general, I’d say that those early Florentine examples followed more of the German school of violin making, whereas our mandolins are influenced more by the Italian school. Regardless, what we really wanted was that response and that power and the ability to finesse” that the best Loars have, and they believe the trade-offs above help them find the sound that has made their F-5 Artist mandolin model so desired. Without a doubt, their admiration for the Loar era of mandolins is evident in every mandolin they have built, including recent mandolins modeled from the voices of some very specific Loars.

The First Wienman Sale

The story of how the Wienmans sold their first mandolin is one of those amazing quasi-mythical stories that seems possible only in Nashville, especially when told by Will Wienman, but it’s true.

“To our ear, we thought our first three mandolins were just incredibly responsive and balanced and powerful, but we’re not professional players. We thought the finish was good too, but you know…we were in a bubble. So we went to Nashville because we wanted to see how our mandolins stood up against all of the mandolins. We had no intention of going to Nashville to sell mandolins. As a matter of fact, none of those first mandolins even had labels in them.

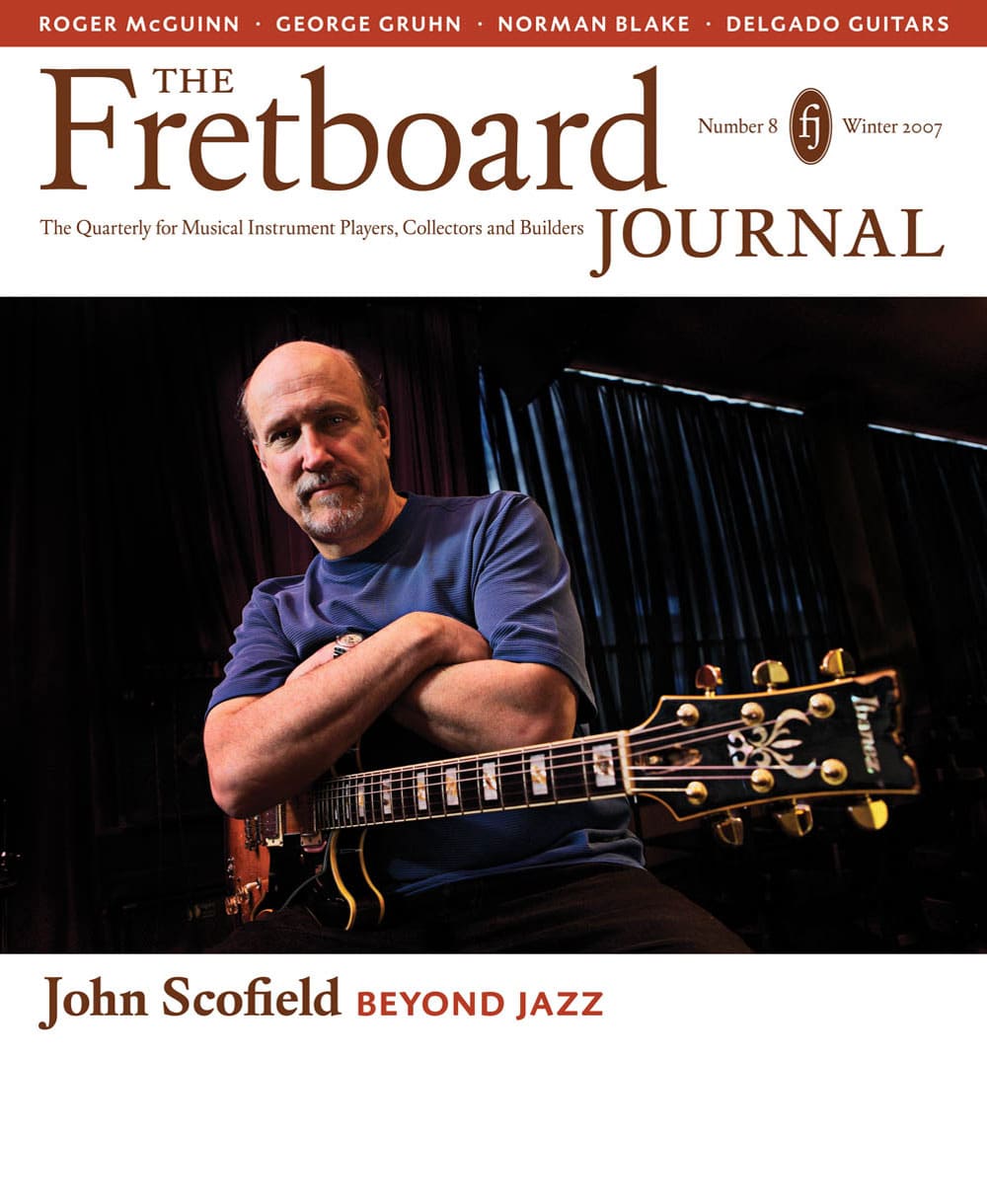

“We made an appointment with George Gruhn at Gruhn Guitars. When we got there, he sent Greg Voros, one of the managers at Gruhn, down to look at our mandolins. He looked at our F-5 mandolin, then he went away and he came back down and said, ‘George wants to see your mandolin. Come back after lunch.’”

When they returned, after a few hours of George Gruhn and the Wienmans comparing their mandolin to a few Loar-era F-5s kept in the famed upstairs of the shop, and George giving them some good-hearted grief about their unrecognizable name on the headstock and a few differences in arching and F-hole shapes, George continued with his obvious interest in the Wienman mandolin. Before they knew it, it was closing time at Gruhn and George asked if he could take one of their mandolins backstage to the Opry that night to show it to some friends. Not wanting to miss the opportunity for their mandolin to get in the hands of seasoned players, the Wienmans quickly filled out a consignment sheet with George, left one mandolin with him and drove themselves and their other two mandolins back to North Carolina.

Legend has it a number of luminary players enjoyed the mandolin left behind in the care of Gruhn. But ultimately, about a month later, Jarrod Walker walked into the upstairs of Gruhn Guitars and made a connection with that Wienman F-5. This was after Jarrod’s stint touring with Claire Lynch and just before he got fully underway as the mandolinist for Billy Strings. Jarrod promptly shot off a message to the Wienmans: “I’m excited to say that I bought your mandolin from George Gruhn today! George took me upstairs and we A-B’d yours with three Loars, a Monteleone, and a handful of Gilchrists. I can honestly say that I preferred the tone of the Wienman over all of them with the exception of one Loar. Even that was a close call. Unfortunately I was short $160,000. I took the instrument home on loan last night, and in the several hours that I played it, it dramatically opened up. The mid-range is out of this world. Balanced, responsive and immediate…I know a good mandolin when I play one, and this one has something special.”

It’s certain that none of the Wienmans or George Gruhn or Jarrod Walker knew that this same mandolin—the Wienmans’ first F-5 (still without a label!)—would, within a few years, be played in arenas and stadiums for hundreds of thousands of fans a year, given the meteoric rise of Billy Strings. Regardless, they all knew that mandolin—and the way the Wienmans were building—was something special.

The Wienman Process: Then and Now

Talking with the Wienmans makes it evident that the combination of Will’s eye for design and Wes’ hands have worked in concert to build mandolins that are consistent from instrument to instrument, both in terms of aesthetics and sound.

Will’s experience in the vintage instrument world over decades has given him an intuitive sense of all manner of instrument design features. And while Will focuses on design ideals, Wes focuses on the slow manual labor required to execute the vision: “It boils down to the pressure of imagining what it’s like to spend so much on an instrument and what [the buyer] expects from it, because I’ve never spent that much on an instrument.”

This combination of the ideal and the practical go hand in hand for Will and Wes. For example, when it comes to knowing when a mandolin is finished, Will says, “When that carved top gets to the point where it wants to speak, then that’s where we slow down…when it really wants to speak, we set it aside and we make tone bars for it. And then we work the tone bars until they really want to speak with the top…and then you get the tone bars talking with each other in this real harmonious, nice sound.”

Wes saw things pretty differently, especially early on: When it comes to carving those last thousandths of an inch from a mandolin top, “you’re inside a cloud of anxiety, and at some point you just have to trust your ears and take it right to the edge but not go over.”

However, in building mandolins full-time since 2017, their process has brought about a consistent product and tone, coupled with those initial aesthetic ideals and meticulous focus. Since those early days, they’ve found efficiencies, built jigs and acquired specialized tools, but it’s still a highly manual process that is a lot more art than science.

At the end of the day, a Wienman mandolin is about Will and Wes’ collective experience, applied to pieces of wood that are by their nature unique, until the point when the wood speaks to them.

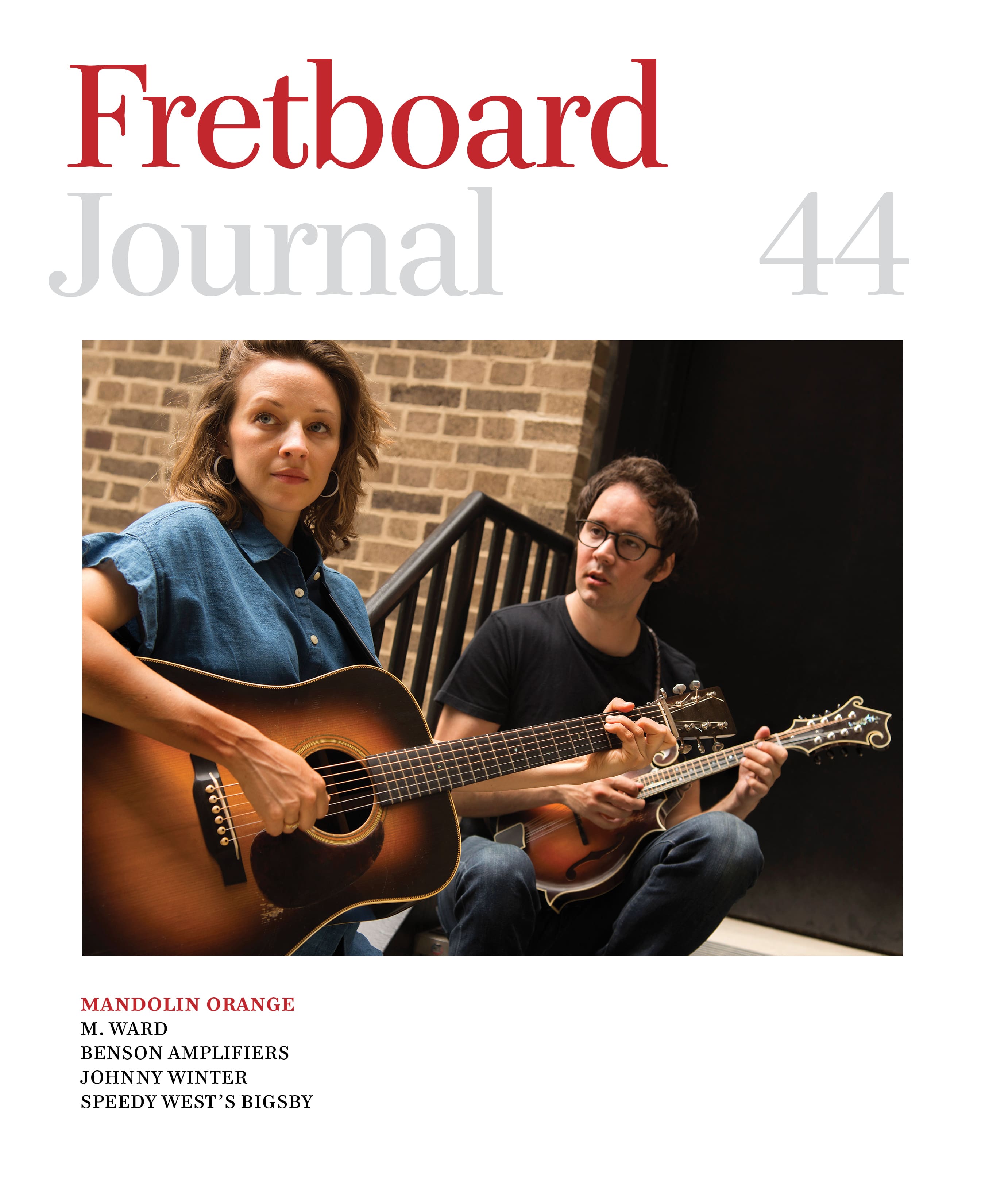

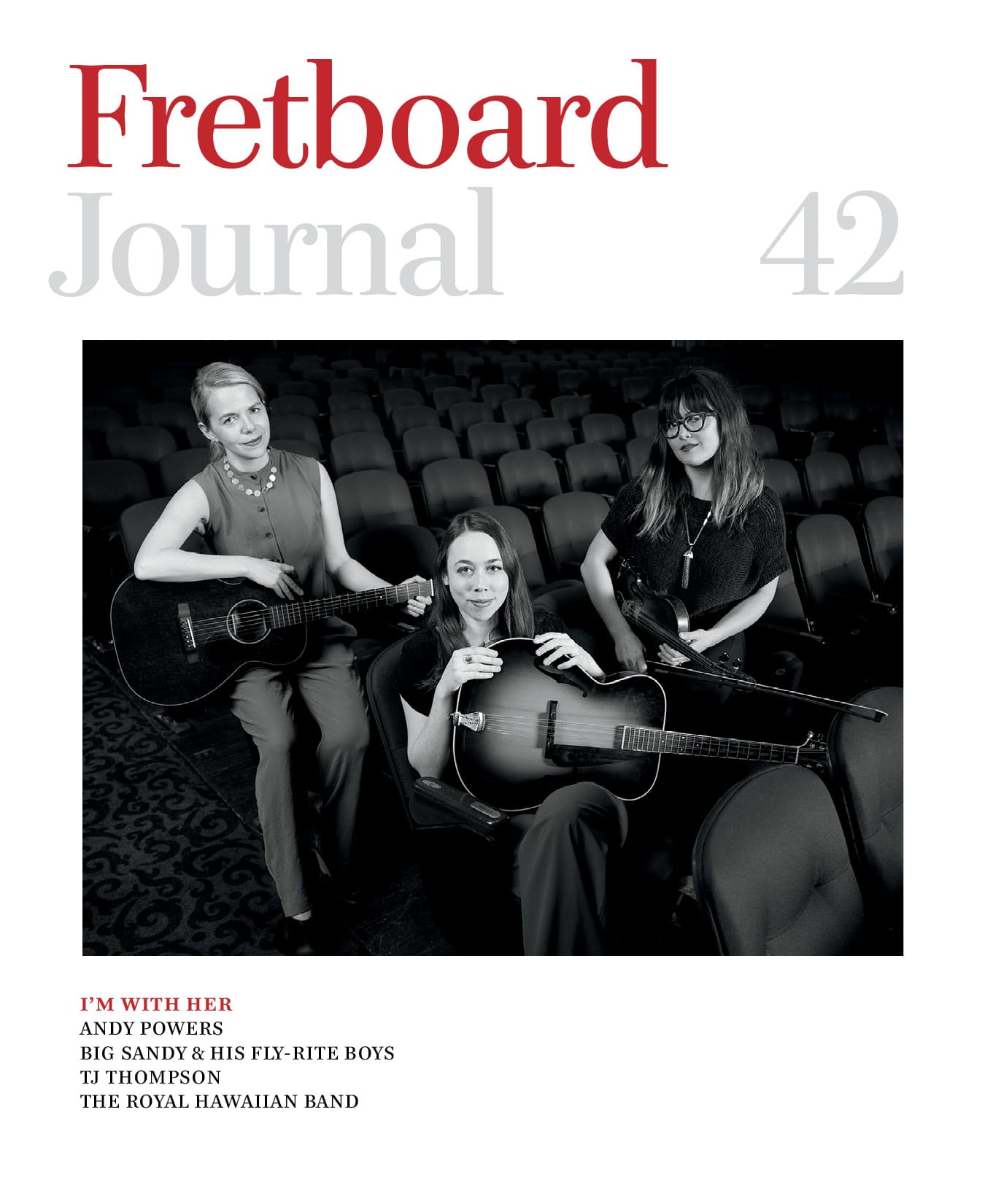

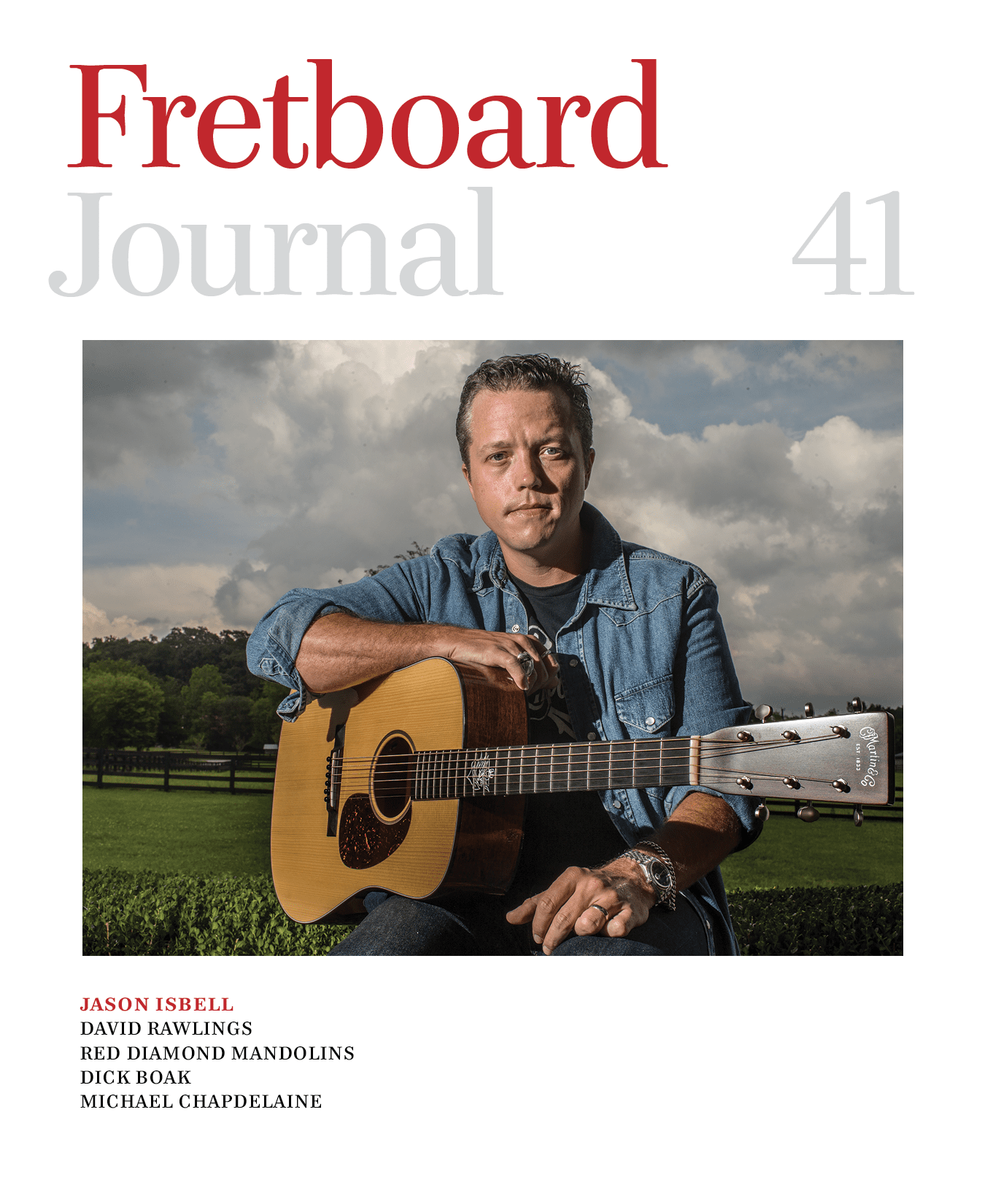

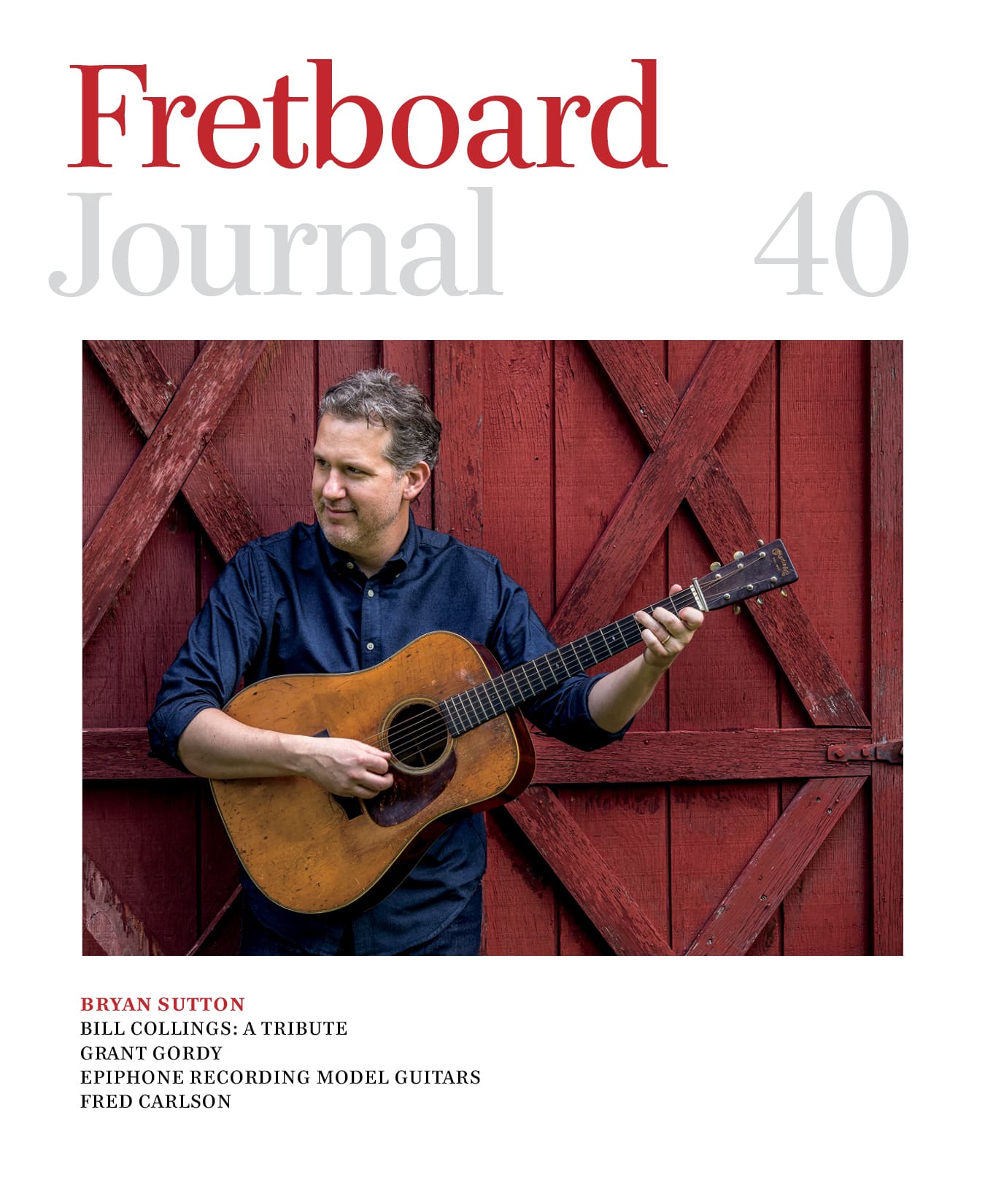

Photographs by Trevor Anthony