On July 25, 2015, President Barack Obama announced the publication of a proposed regulation that, if adopted, would ban “the sale of virtually all ivory across state lines,” with exemptions for antiques and items bearing only de Minimis amounts of the substance. The regulation would also maintain the existing ban on importing ivory for commercial purposes and, with an antiques exemption, extend that ban to exporting for commercial purposes.

For the legal and factual underpinnings of this new proposal, including the Obama Administration’s February 11, 2015 announcement of a National Strategy for Combating Wildlife Trafficking, see my previous missive on this subject. That epistle also addresses how to ascertain if your guitar contains the questionable white stuff. Do remember, though, that the African ivory that is the target of this proposal was, as John Frederick Walker observed in Ivory’s Ghosts: The White Gold of History and the Fate of Elephants, “the plastic of its time, used for everything from buttons to scientific instruments to billiard balls to geegaws.” Into the early twentieth century, it was also used in saddles, nuts, bridge pins and sometimes bridges and inlays on guitars.

OK, preliminaries completed, let’s get straight to the question of how the regulation will affect the movement and sale of musical instruments containing ivory.

Travel

This is a proposed federal regulation, so it only affects activities that cross state lines and the US international border. So, feel free to wander about your neighborhood, city, or state, regardless of the DNA content of the components of your guitar.

You can freely wander about the US, too. The proposed regulation does not affect interstate travel.

As for international travel, the proposal simply restates the existing policy of the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the agency charged with enforcing the nation’s domestic and international environmental laws and the agency that promulgated the proposed regulation. Chief among those laws is the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). A couple of years ago under the auspices of that treaty, USFWS created a procedure for acquiring a Musical Instrument Certificate, or passport, that makes it legal for you to carry across international borders musical instruments that bear endangered species like Brazilian rosewood, tortoise shell, and, of course, ivory. My how-to-obtain-a-passport article is here. In short, as regards ivory, your instrument must meet these requirements:

· The ivory was legally acquired before the date when ivory was added to Appendix I of CITES, the treaty’s most restrictive category, February 26, 1976;

· You’re carrying that Musical Instrument Certificate; and

· Authorities can match the instrument to the certificate by serial number or other identifying features.

Once you’ve got the passport, you can travel about to any of the nations that recognize a CITES passport. On your journey, you’re legally entitled to use your instrument for personal enjoyment, for the annoyance of those who hear you play, and for performing paid gigs. But, remember, you can’t legally sell it unless you comply with the US export requirements of the proposed regulation, which I address below.

Interstate Sale

This is the regulation’s biggest proposed change. Initially, USFWS intended to ban all interstate sale of objects bearing the illicit, white substance. But, after receiving “input from the public, including musicians and musical instrument manufacturers, museums, antique dealers, and others who may be impacted by these proposed changes,” the Service tempered the proposal by allowing for sale in two instances.

Antiques

First, you may sell your ivory-bearing guitar across state lines if it is an antique, as defined by section 10 of the Endangered Species Act. Accordingly:

· It’s at least 100 years old;

· It may not have had its ivory parts repaired or modified since December 27, 1973, the date of the enactment of the Endangered Species Act (ESA); and

· It if was imported, it arrived ashore through a designated endangered species “antique port.”

What’s an antique port? On September 22, 1982, the U.S. established 13 “antique ports” through which ESA-listed items must be imported: Boston, New York, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Miami, San Juan, New Orleans, Houston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Anchorage, Honolulu and Chicago.

Ah, you say, great, great, great, great, great, great grandpa brought the guitar ashore on the Mayflower in November 1620. If the item arrived before the antiques ports existed, any port, even Plymouth Rock, will do. The burden of proof, though, lies with the person claiming the exemption. You’d better hope that Captain Christopher Jones made a note of the guitar in the ship’s log.

So, go ahead and list for sale on eBay or Craig’s List that ivory-bound Civil War era Martin or the Renaissance-era, European lute. However, specify “for sale in the lower 48 only” because, as we’ll see, in most cases you won’t be able to transport them legally across international boundaries.

De Minimis

Your guitar is old, but not that old, you say, and it does contain bits of ivory, like the nut and saddle. Well, USFWS turned to its Latin-talking lawyers to create an exemption just for you. If the guitar contains but a de Minimis, or insignificant or trifling amount of ivory, you can sell it across state lines.

One person’s “trifling,” you think, may be another person’s “significant.” Those same lawyers helped you out here, too, by, apparently, dusting off their scales of justice and weighing the ivory veneers of piano keys. It turns out that “the approximate maximum weight of the ivory veneer on a piano with a full set of ivory keys” is 200 grams, or about 7 ounces, if you’re feeling imperial. That limit, the Service opines, should also cover the decorations on musical instruments and “insulators on old tea pots, decorative trim on baskets, and knife handles, for example.”

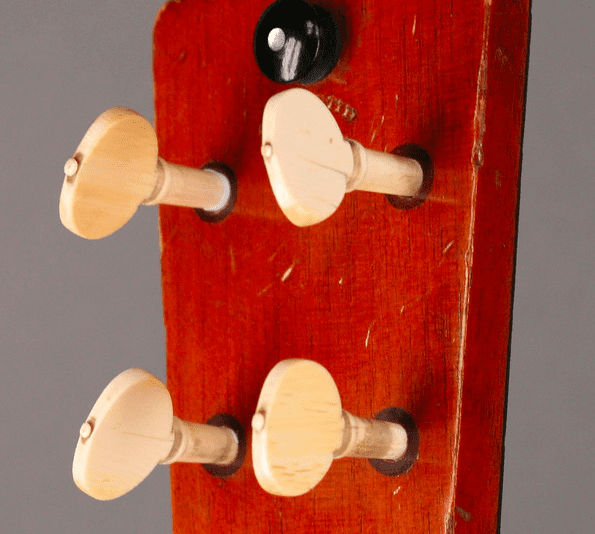

So, because I suspect that even an ivory binding, nut, and saddle, won’t weigh more than 200 grams, you’re free to sell your post-1915 Martin across state lines. But, what if you have a guitar that doesn’t qualify for the 100-year-old antique status, but it has those ivory components plus ivory bridge and friction tuning pegs? You’d probably better get out that scale and figure out how to weight the ivory components.

Oh, and those ivory components need to be, well, pretty old. The ivory must have made its way into the US before the date when the CITES members voted to list African elephant on the treaty’s list of endangered species in its Appendix I, or January 18, 1990. As always, the burden of proof lies with he or she who is claiming the exemption.

Finally, despite the many-great grandpa’s role in this tale, the de Minimis rule does not contain a grandfather provision. The item you’re selling must have been manufactured before the regulation’s effective date, which will likely occur around this time in 2016.

Other considerations

So, you can sell your ivory-bearing guitar or violin bow or teapot across state lines if it’s a 100-year-old antique or it bears only a de Minimis amount of ivory. Imagine a post-1915 ivory-encrusted guitar with more than 200 grams of the white stuff or grandma’s Deco-era Erté ivory statue. Should the rule go into effect, you won’t be able to sell them to someone in another state (or, as we’ll see, in another country). What if you only want to get your treasure spruced-up at Greg’s Guitar Repair or Ivan’s Ivory Restoration? No worries. The rule applies only to “trade,” which involves change of ownership. Shipping for repairs is not covered. But, you won’t be able to allow Greg or Ivan to sell your treasures to admiring customers who happen to walk into their shops.

Finally, USFWS also addressed “Foreign Commerce.” This is a sale that involves an object in a foreign country, but the resulting transfer involves neither import into nor export out of the US. Huh? Well, suppose that you inherit an old Martin from uncle Willi, who lived in Tübingen,Germany. Given the legal hassles you’ve now discovered are involved in getting the thing to your home country, you instead sell it to a picker named Andrea in Savona, Italy. Because you’re domiciled in the US, US law applies to the transaction. This new regulation has a provision just for you. Both the antique and de Minimis exemptions apply here, too. However, the ivory must have been removed from the wild before the African elephant was first listed under any provision of CITES, or February 26, 1976. And remember, legalities under German or Italian law are another matter.

Importation

All right. We’ve covered the globetrotting, gigging musician and sales within the US. What about commercial importation across the US border? It cannot happen legally. The proposed regulation prohibits commercial import of ivory, period. Neither the antiques nor the de Minimis exemptions apply. One simply cannot purchase anything outside the US that contains ivory and have it shipped into the US. That old, ivory clad Martin, once sold outside the US, cannot return home, at least while bearing its ivory bits.

Non-commercial transportation, like that peripatetic musician, a museum exhibit, or a household move that includes grandma’s ivory trinkets is OK. However, you can’t then sell the stuff you’ve brought in under the exemption.

Exportation

The proposed regulation also dramatically limits export of ivory. As with importation, the de Minimis exemption is not available for exportation. So, in most cases, neither you nor that vintage guitar shop can sell and ship that ivory-bearing Martin to a purchaser in Europe. If the guitar merely has an ivory nut or saddle, the seller will be replacing those items with bone or plastic before shipping.

The antiques exemption, though, does apply. So, you and the dealer can sell that ivory-bound, Civil War-era Martin, or any object that’s at least 100 years old, to the buyer in another country.

The non-commercial musician, household, and museum exemptions do apply in exportation, just as they apply in importation.

Effective Date and Comment Period

Ah, but this new chunk of legalese is but a proposal. How will it become law? you ask. Following typical administrative law procedure, USFWS will publish the proposed regulation in the Federal Register on July 29, 2015. The Service will then allow public comment through September 28, 2015. After considering the comments and making whatever modifications is chooses to make, the Service will publish the final rule. The time lapse from end of commenting to final rule typically takes between six months and a year.

So, read the rule, chat with your favorite guitar-playing lawyers and administrative law judges, and send those cards and letters (and email comments) to the USFWS.