A little history lesson: Back in 1965, Ry Cooder and Taj Mahal had a band called Rising Sons. It lasted just a year, during which they recorded one Terry Melcher-produced album. The project stalled, got bootlegged, and wouldn’t see an official release until 1992. By that time, Cooder was already a guitar hero for his years of legendary session work, his stint with Captain Beefheart, his solo albums and scores. Meanwhile, Taj was already a blues music hero, a world music pioneer and a soundtrack composer.

As the decades passed, it seemed more and more unlikely that these two old bandmates – both masters of their respective genres, both with a penchant for amazing collaborations – would ever perform together again. But Taj and Ry continue to surprise and – a mere 57 years after those Rising Sons sessions – they’ve released an album featuring the music of Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee. Get On Board: The Songs of Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee (Nonesuch) is a laid-back affair: Two old friends cherry picking songs from one of their shared early influences in the living room of Ry’s son, Joachim Cooder.

On separate phone calls, I spoke with both Ry and Taj about the project, the complicated working relationship that Sonny and Brownie had, the gear they employed, and more. Of course, I also had to ask Ry about his recently-sold Coodercaster, too.

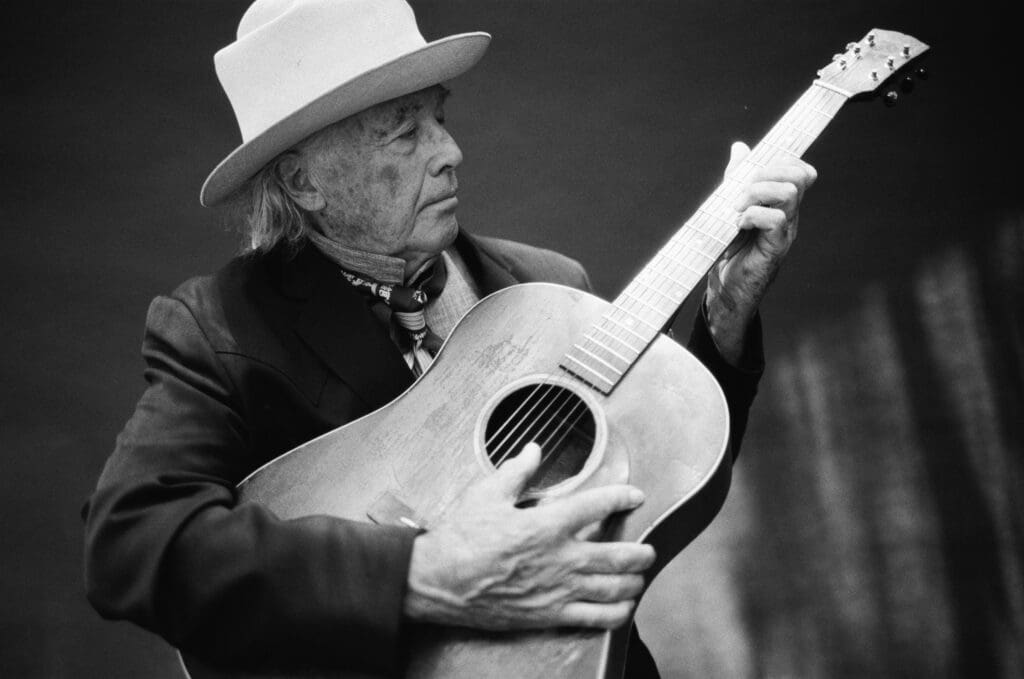

Ry Cooder

Fretboard Journal: A couple of years ago, your son, Joachim, created what I consider a truly great record paying tribute to Uncle Dave Macon (Over that Road I’m Bound). I’m wondering if hearing him re-interpret those old Macon songs in a new way influenced you and Taj to re-interpret these tunes?

Ry Cooder: I wouldn’t exactly say that. Taj and I started speaking together on either email or by phone a couple years ago, before COVID. He was an honoree at one of those Americana [Music Awards] tribute shows that they do at the Ryman, when me and Joachim were in the house band. Taj was there and I hadn’t seen him in years and years because I don’t get out much. He travels all the time, but I don’t. That night, he said, “What should we do?” I said, “Man, just get up there and let’s do ‘Statesboro [Blues]’ and we’ll just stomp it on down to the bricks.” It’s not hard to play.

After we did it – and it was really good! – I remembered how we used to play together. Right along, Joachim has been saying that if Taj and me did a record, people were really going to like it.

I usually try to do what [Joachim] says to do. I usually agree with him. Then, it’s a matter of what would you do if Taj and I were to sit down. He likes all that blues stuff, a lot of which is very esoteric or antique or obscure in terms of making a record now. What would the two of us do?

It suddenly was obvious to me… Brownie and Sonny. It’s a template, you see? We could take off on that: He plays harmonica and I can be Brownie, to some extent. We know enough about music at this point in life that we ought to be able to pull this off and the songs are good. That’s the key to it.

You can you sing Sleepy John Estes tunes, but nobody’s going to know what you’re saying, because that kind of life and that kind of thinking is long gone. It’s over the hills and far away, unless you’re a devotee.

But Brownie had cracked the code. I figured, let’s do the same thing. We’ll sing these songs. They’re good songs, they’re simple and fun to play. We know this stuff, so why not?

Taj said it was a good idea; he thought it was worthwhile. So we agreed to get together and the three of us, in Joachim’s living room, which I knew was good because it’s acoustically perfect. We had done a lot of work in there, me and Joachim.

It wouldn’t be [in] a studio and it won’t be so formalistic. We can just relax and sing and play like we used to do in the old days. And that’s exactly how it went.

FJ: On some of these songs you guys stayed pretty true to the template laid out by Sonny & Brownie. But then on some, you’re playing mandolin, or you’ve got your electric guitar. And then there’s Joachim’s percussion. Did it take some convincing for Taj to agree to these variations or did it just happen naturally?

RC: I think he just thought it was good. You sit there and you have your earphones on. Engineer Martin Pradler is going to move mics around until he gets the room focus. That’s what they used to do for Phil Spector, the same thing. Get that room going, get the saturation going, get the vibe going. You sit there with earphones on, you like it. And Taj liked it. We went ahead and there was no mastermind. You just sit down and play. One take, maybe two? Hardly more than two. I wouldn’t like to think we went to three takes. Then you start overthinking!

Keep it fresh and then just respond to the thing itself. The tune takes you somewhere and you just go there. And then listen back. If it seemed good, go to the next one.

We had a list of the tunes we thought would work together. Get variety in there, get a little different. Of course, I changed to mandolin a little bit, just to vary it, just to have something else to do: Gives you another focus or some more inspiration… to somehow catch a groove differently.

FJ: Did Taj play guitar on this record?

RC: He played a little guitar, a little piano. The piano was a surprise. There was a beautiful old Steinway in the room. We were on a break, I suppose, and he sat down and started to play it really well. I thought, “Wait a minute, let me go in and sing something!” By the time I got to my chair and put my earphones on, I figured out that “Deep Sea Diver” will work. And I hoped that he wouldn’t stop, get bored, and get up. He kept playing and I just started to sing it. You can hear it fade in, because there was no start. So, that was just strictly off the top of your head, that thing. He did play guitar on “Pawn Shop.”

FJ: When it came to selecting the songs, did you even need to re-listen to these or are these songs just in your DNA from growing up?

RC: Some of them are. I had to poke around on YouTube and look for some things. I forgot about “Hooray, Hooray” … that’s a knockout, that song. I’d forgotten about that. “What a Beautiful City” I remember they used to do. “Packing Up, Getting Ready to Go” was an improv thing. That was just sort of out there, somewhere. But some of the songs were on the original Get On Board and then some of them aren’t.

They had a huge repertoire. They must have made fifty albums or more. Up to a certain point in time, they’re really good and then after that point in time, they’re not so great anymore. It gets to be awfully rehashed just by rote. You don’t want those; the early records are the thing.

FJ: They weren’t the first to record “Drinkin’ Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee.” It was a Stick [McGhee] song, right?

RC: Stick did it. I think they recorded it after the fact, but brother Stick had the jukebox hit. That’s a whole other story. They did do it, though.

FJ: What is the story there?

RC: Well, I don’t know too much, except it has something to do with Atlantic Records because they did Stick McGee. Who was he, after all? He was Brownie’s brother. He recorded it and then Atlantic got their hands on it and issued it. It became a hit, because they had the distribution, of course, and the jukebox machines. They had that deal with the mafia, I think, who controlled the jukebox machines. That would be an interesting chapter in a book of unlikely songs that got to be hits.

FJ: I’m assuming you saw Sonny & Brownie when they were around at the Ash Grove?

RC: That’s right. They opened the Ash Grove. They were the first.

FJ: Listening to Sonny & Brownie – and maybe most of the old blues duos these days – seems almost quaint. It’s not the cool thing; everybody wants to hear Charlie Patton or Son House or some other raw-sounding solo artist. It was great to hear you breathe life into these tunes, just like Joachim did with his Uncle Dave Macon project.

RC: Well, you’re right. That’s kind of the job at hand, I’d say. That’s the mandate. You know what I mean? You have to be able to pull it off. It’s no good having a concept that’s a bad concept.

FJ: What are you playing these days when you’re just at home?

RC: Well, I play guitar … and banjo is good for your coordination. Banjo, especially what they call a round peak banjo, that frailing style. That’s really good for your brain when you get older, to keep your hand to eye coordination right.

Keep your chops really up. I do that. That’s my physical exercise. Getting ready to do this, I practiced a lot because I hadn’t played that stuff in years. So, I did get myself in gear.

We’re doing two nights at The Great American Music Hall up there [the San Francisco show takes place May 19-20, 2022]. We can do other songs, too. It’s an hour-and-a-half show.

[We’ll] see what it’s like and see if we like doing it. I’m practicing, I’m looking at different instruments that I’m going to want to use because the stage is very different from the living room. You can’t say that it’s the same and so you can’t approach it quite the same way. We’re going to do things slightly differently, but keep that good groove… the three of us going. Joachim can play his mbira as a bass and play… He’s got three arms, I don’t know how he does it! I really don’t. It’s amazing to see. Taj has never seen anything like it.

FJ: I watched the making-of video that Nonesuch Records put out and there are a couple moments where you’re playing with a thumbpick. I thought you hated thumbpicks?

RC: I do hate thumbpicks, but you have to play it that way. To play Brownie McGee, you have to have thumb and fingerpicks, which I hate.

It’s so clumsy and painful to me. You’ve got to clamp them down so hard, it hurts my fingers. I don’t like it. When we were playing though, you have to get that sound that he got, which is very forceful on the D-18, which is a bluegrass instrument, really.

Ry Cooder’s 1946 Martin D-18.

But you, if you’re going to a fingerpick it for God Almighty’s sake, you have to have those surfaces on your hands to make that stuff really work, to really speak, to really bark. I kept losing the fingerpicks, they kept falling off. I had a terrible time.

I’m playing Mike Seeger’s picks that came with one of his banjos that I bought after he died. They sound really nice because they’re soft metal. New fingerpicks are no good. They sound terrible.

It’s not the way I like to play, at all. But you have to do it. Then, I thought, “Onstage, I’m going to play one of these archtops with the old, DeArmond microphonic pickups in it. Then I don’t have to play so hard and I can play with just the thumbpick and fingers. I won’t need the fingerpicks so much.

FJ: Did you experiment with any guitars besides your D-18? Back in the day, did Brownie use a Gibson or something cheaper?

RC: Well, he had one of those “Banner” J-45s, I think, at first… when he was trying to be an R&B guy. Then, somewhere, probably in the early ‘60s, he got ahold of his D-18 and he made it work. If your action is low enough, you didn’t get some of that string flapping effect that he got, that’s nice. It gives it another quality.

On one of these songs, I think it’s “Beautiful City,” I’m playing an Adams Brothers. It’s big, the size of a guitarrón. It’s huge. I can barely wrap my arm around it, it’s so big. Deep. It must be a foot deep and a little bitty neck on it. God, it’s the weirdest thing. The scale length is strange.

FJ: Adams Brothers?

RC: Yeah. Check that out. It was built in 1904 or 1905. It’s like nothing you’ve ever seen, but it has this huge sound. Sounds like Leadbelly, but it’s only six strings. It’s very resonant and very beautiful, but you can only play in the position of G. It’s crappy in other keys; it’s no good. It doesn’t fret in tune at all, but in G, you feel good. D, G, maybe C…

You don’t tune it in A440; you have to tune it low. But listen to the track “Beautiful City.” You’ll see what I mean. It’s got a real amazing sound and that was fun to try. I got that from Bernunzio Instruments in Rochester, New York.

Cooder’s Adams Brothers guitar.

FJ: Is that a recent acquisition?

RC: Yeah, I’ve only had it about two years. It’s almost unplayable. Except in the position of G. But it’s amazing. I’m working on it all the time. You can flatpick it and then you get a little more sound out of it.

You feel like a marathon runner when you play that thing. It’s tiring, but it’s good. It’s amazing.

FJ: What’s the electric on the album?

RC: On the first track, it’s an overdub bottleneck, so it’s the Stratocaster, the one with the pickups. It sounds okay on that song. I’ve got this weird Japanese solidbody that’s the goofiest electric that’s ever been made, but it sounds like Elmore James. It’s incredible.

FJ: Your Guyatone?

RC: It’s called a Stella. It’s very beautiful.

I mean, it is so primitive and it’s an absolute piece of shit, but it sounds amazing. There again, almost unplayable, but when you do, if you get the key right for bottleneck, it’s great. It’s always sensational. If you have the right amps, of course. You have to have that. That’s what people just don’t realize. These things are only as good as the amps you play them on.

For this kind of music, you have tiny little amps. You don’t want to be loud. You want to sound big, but you don’t want to be loud, right? I mean, it’s not about that.

FJ: Do you know what you will take on the road?

RC: I’ve got a good combination. It’s a tiny little Standel. It was a special order so it’s got an 8″ speaker. Little… about the size of a Princeton. The other one is the mate to it, a TV-front Fender Deluxe, really old. Beautiful. That’s just great. It’s pristine condition. The third thing is one of these Harmony’s, made for Sears.

That’s just absolute junk, but, god, it sounds good. It sounds like blues. Those blues guys, they didn’t play loud. I don’t know why people think blues is loud. It’s not loud. Besides, they didn’t have any money. Look at what Howlin’ Wolf played!

They played cheap amps, like Luther Perkins did when he was with Johnny Cash. He played one of these Harmony’s. That’s how I found out about it.

It’s terrible. And the question is: Is it going to last two nights? I don’t know if it will. I’m not sure. It’s so fragile. If you look at it cross-eyed, you break it.

FJ: Not long ago you sold one of your Coodercasters through Retrofet. Do you miss it?

RC: No, no, no. That’s a nice guitar, but if you can get $150,000 for a guitar, you should get $150,000.

I mean, you really should. That’s good money! I wouldn’t sell the one that I kept, the brown one. That’s the one that’s got the sound you can’t replicate. Nobody can make that again. I tried, but it can’t be done. I don’t know why that one’s as good as it is, but it is. It’s just really good.

I think it’s the springs in the body. The springs are there. You shouldn’t take the springs out. But anyways, I’ll keep that. I’ll be buried with that. Hopefully not soon.

I’ve been selling guitars. I have too many. I can use the money. I’ve got these old cars and they need work all the time, so I use the money from the guitars to fix the cars.

Taj Mahal

Fretboard Journal: How did the idea for this album come about?

Taj Mahal: Well, Ry and I hadn’t played together since the late ’60s, probably ’66 or ’67, right around there. I [recently] got a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Americana [Music Awards] people, and I was presented the award by Keb’ Mo’ at the Ryman Auditorium. Ry was involved in the band that was there and Don Was, Ry’s son Joachim, and Buddy Miller.

Before the award came out, they said that Ry wanted to talk to me about material. So I thought “Ryman Auditorium might be the place to sing a little more Georgia country style. I sent my choice in, and Ry got right back to me and said, “That sounds really great and all. Let’s really stomp ‘em down.” I was all for that. We went there and played, and I think that was good.

Little by little, we started communicating with one another and eventually, I said, “Hey, what do you think about playing together? Maybe we should try to do something.” So he said, “Well, come on down and we’ll see what happens.” So I came down and visited him at his home, brought my instruments over, and we played and talked. Did this, that, and the other thing for two or three days and that satisfied the situation for a while.

And then we passed some music back and forth, things that we like. It wasn’t like every day we’re on the phone talking or anything. It just happened when it did. And then, Ry shot back to me and said, “Hey, I’ve got this concept. What if we took the music Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee and we created that thing with the two of us?” It sounded absolutely fabulous to me. I was in from the first inception.

Then we set the thing up, gave a listen to the tunes, and got the lyrics out. He set it up at his son’s house. And we just went at it, it’s like here it is… here’s the tree, here’s the axe, let’s start chopping them down.

FJ: Did you even need to re-listen to these songs? Or are they just in your blood?

TM: Well, they’re in the blood, but it was nice to listen to them again, just to see if there’s any specific things you want to get across. If you go back and listen to those guys, they had been doing it professionally and it got real tight and pretty well-polished up. Our stuff sounds raw – front porch-y, back porch-y, living room-y – fun, ragged, but soulful. I’m really glad that we could create something like this, you know?

FJ: Before this project, how often would you listen to the music of Sonny and Brownie?

TM: Anytime I want to. I’m listening all the time to the musicians that I really like. I’m always acquiring new stuff: I was listening to Teddy Edwards the other day, I listen to Art Tatum, Tiny Grimes, the banjo player… Elmer Snowden, I’m listening to different things. Ry will shoot me of something he’s heard that’s really incredible and I’ll shoot something back.

As much as we know, there’s a lot of blues stuff that never got produced, that you’ve never heard. Fortunately, there have been some people who’ve been smart enough to put some good stuff out. And if you’re a music buff like Ry is and I am, we’re in it.

FJ: Did you only play harmonica? Or did you pull out the banjo or the guitar?

TM: I played harmonica, guitar and piano.

FJ: What guitar did you bring?

TM: I brought a Gibson Keb’ Mo’ gave to me. This is his signature guitar that they had made for him. It has a great sound and then I brought various harmonicas to play.

FJ: I know that you got to see Sonny & Brownie perform a bunch back in the day. How well did you know them?

TM: They knew me by name. We used to go over the Europe a lot and they knew us pretty good. We talked all the time, because to me, they were like my older uncles… not so much like my granddad, but mostly like my older uncles.

There are elders in a village here in Africa. There are elders in a village in the south, you know? I was raised to be respectful of those people. Plus, they were about the music.

FJ: What was their dynamic like? I know they’d split apart, come back together… it was a business for them.

TM: The music was what they were there for. Some people know a lot more about their animosity with one another. I know a few little stories and I was present, during a couple of minor incidents. But that wasn’t really what it was about to me. It was always about the music. I didn’t go down that rabbit hole.

FJ: Did they show you any tunes or teach you in any way?

TM: No, only by watching how good they did what they did. That’s the only way they taught me.

I think the thing that’s most important when you’re a musician: You realize that it’s not because somebody wants you to do something…. you do it because you love it. They loved the music. It’s their show and their language.

FJ: You and Ry get a little wild on some of these songs. Did you guys have any artistic differences about how to interpret these tunes or did it just kind of flow naturally?

TM: Not one. All naturally.

FJ: It’s a great record.

TM: Yeah. That’s why I say it’s like raw, front porch-y, back porch-y, living room-y, ragged-but-right soulful. I enjoy it.

FJ: Are there any other artists from back in the day that you could see you and Ry revisiting like this?

TM: Oh, lots. There’s more music than most people have time to listen to. Thank goodness for that.

It’s just that popular music has derailed people. It’s snared them off the path of discovery and said, “No, you don’t have to go over there. We have it right here. Go put it in a little package for you… now there’s only two degrees on either side of this that you can look at. Don’t go anywhere else, stay right here and we’ll just make sure that you get what we want you to have.”

I’m serious. It’s so narrow. It’s like… that’s just not how the world is, you know?

You’ll never ever hear all the music that’s here to hear on planet Earth in a hundred lifetimes. It’s not possible.

FJ: Too true. Thank you, Taj.

TM: It’s my pleasure that you guys really enjoy it and you get it. When Ry and I were in Rising Sons, they did not get us. So it’s really kind of nice that 57 years later everybody gets us. Here we are, almost 60 years later…

Artist Photos: Abby Ross