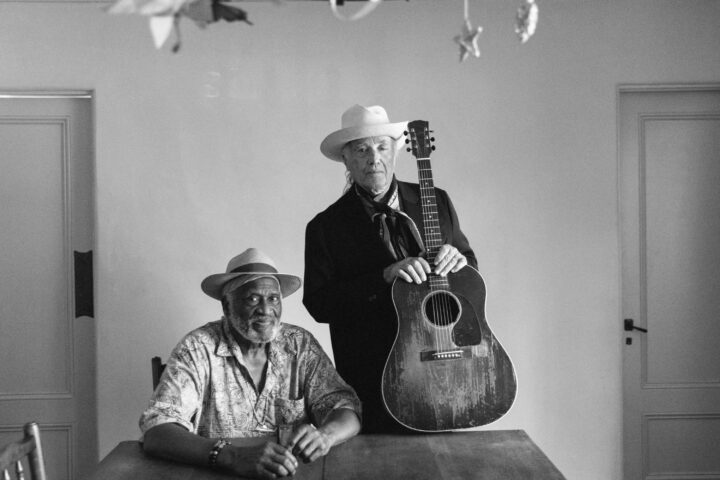

Like so many of us, Fretboard Journal reader Stewart Milne is a huge Ry Cooder fan. Unlike most of us, he’s also an accomplished visual artist.

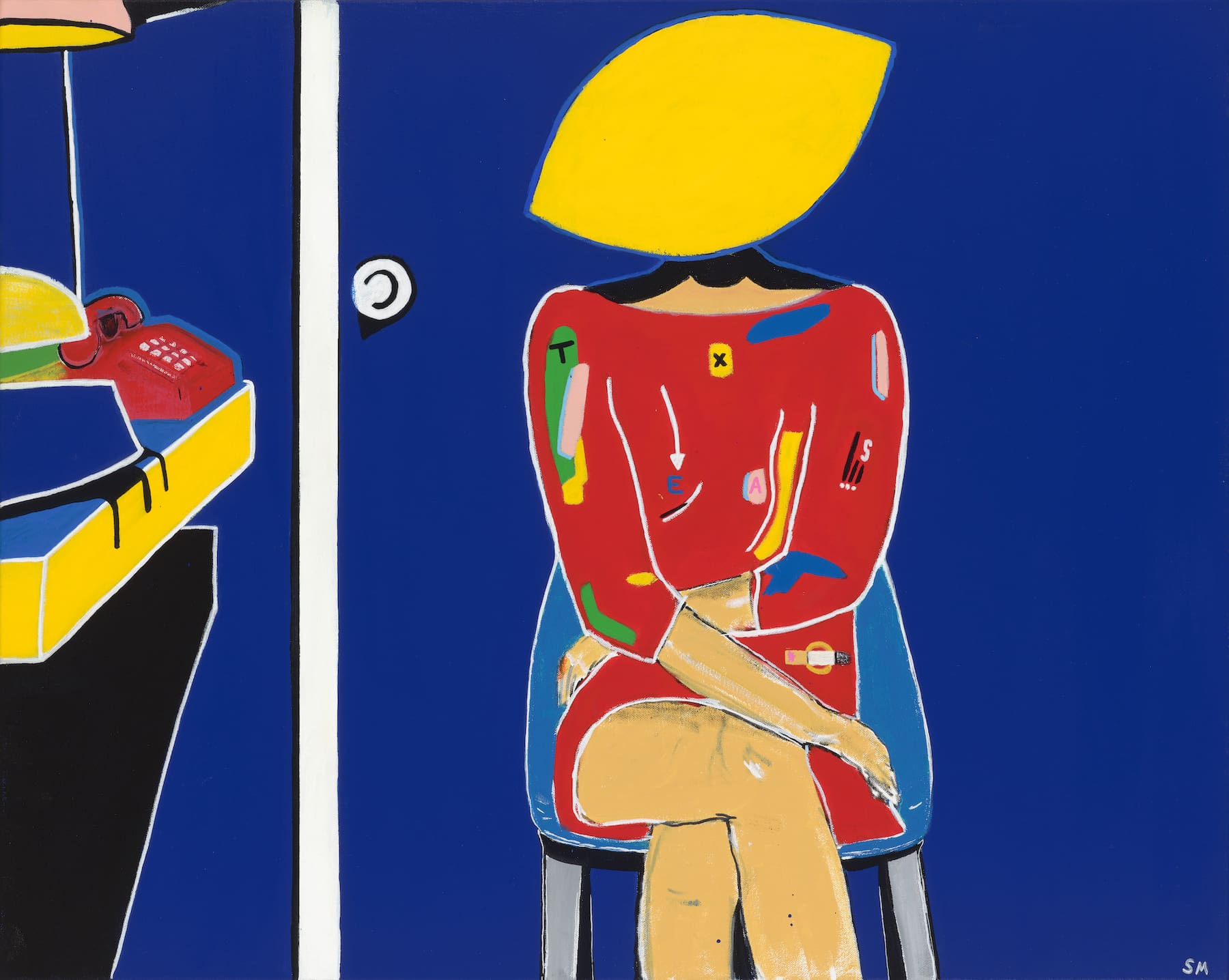

Thanks to Cooder’s soundtrack, Milne discovered Wim Wenders 1984 movie, Paris, Texas. He subsequently created a series of paintings inspired by the film. The art is now on display at Toronto’s Lyceum Gallery.

Milne’s show runs through July 25 and we wanted to hear more about it…and his love for Cooder.

Fretboard Journal: Tell us about your work as a visual artist.

Stewart Milne: Well, I’m almost entirely self-taught and only began painting a few years ago. It started out by just trying to paint a photo or my reflection and some cool things came from it. Each piece would teach me something and here we are.

My grandmother, mother and aunt all paint so it’s something that has been around since I was young, but I never thought it was something I could do. I think I believed that you needed to be great right away, otherwise you’re no good. Of course, that’s not the case with, well, anything.

I didn’t consciously create the style that I paint in, but looking at my work over the past few years there is definitely a great affinity for primary colors and saturation. Again, I’m not sure why that is, but each piece is almost like math and, by the end, it has to add up. Having no formal art training or education helped that along since mixing colors usually resulted in mud, so I would stick to the colors that I liked right out of the tube or the can. Where the rest of the influence comes from is hard to pinpoint and maybe not even necessary to do so, at least coming from me anyways.

Most pieces are not sketched out or worked out and they usually come from trial and maybe a loose concept that often leads someplace new. Two great pieces of advice I received early on were, “you have to try, to know” and the one that got me moving was “paint what you see.” I just try to do that.

It can feel scary trying stuff when you’re sort of loving it because you’re afraid of ruining what you have, but the luxury with paint say versus live music, is you can paint over it. That’s usually the time when things start to happen as well for me, when it’s a bit uncomfortable and I’m kind of up against myself a bit.

FJ: You’re also a guitarist?

SM: I guess I am. I can’t seem to get enough of the instrument. The more I play, the more I find out how big the universe is between just me and the guitar…it’s wild.

My mom started me on guitar when I was young. My sisters got the piano and violin and, for some reason, I got the guitar.

Fretboard Journal and my love for vintage guitars came to me by way of a few happenings that I think are worth sharing. I went on a fishing trip with my dad and his friends out off the coast of Vancouver Island a while back and that’s where the vintage guitar seed was planted. Up until then, I had the same guitar for a long time, an Alvarez 000-size all mahogany kind of thing. It was a pretty sounding guitar. And then on this particular trip my dad’s good friend, Paul, busted out a 1933 Kalamazoo KG 11 with the prettiest small burst. That guitar changed everything for me. It was like a different instrument altogether.

I came home from that trip dead set on finding its twin. I threw Kalamazoo into Google and Folkway Music popped up in the results. Little did I know that one of the world’s best shops was only an hour away. Off I went to Folkway and, while I didn’t land a ’33 KG 11, I did find an education and a place that is unlike any other I’ve found since. I realize I’m drifting here but it really was a life-changing experience. Mark Stutman and the guys there have something special. I could go on, but I think you know what I mean. I wouldn’t have the guitars I do now without their guidance and support. It wasn’t long after finding Folkway that I was tipped off to the Fretboard Journal and to be chatting with you now is quite the trip. As I mentioned to you before, I’m so glad someone (FJ) is keeping the nitty gritty alive and thriving. It’s all about the details.

FJ: How did the Paris, Texas project come about?

SM: I had a lot of blank canvases staring back at me. After doing my first big solo exhibition last summer, I wanted to try another. I didn’t have the idea for a whole show at this point, but Paris, Texas was screened at this local theatre (the Playhouse). I had known that Ry Cooder did the soundtrack and was familiar with the songs, but for some reason didn’t really put two and two together. I went and saw the film and was kind of stunned. It really sunk into my skin and I couldn’t stop thinking about certain aspects of it. It’s like an elephant sitting on your chest, you can’t escape it. It continued to hang around in my thoughts and I decided to try painting the iconic peep show scene from his view. I wondered if doing a whole series on the movie was possible or maybe it would be too tacky, but I just went one at a time and tried not to zoom too far out until they were all finished. Now that it’s complete I know I did the right thing that day, going to see the film.

FJ: What impact did this movie and music have on you?

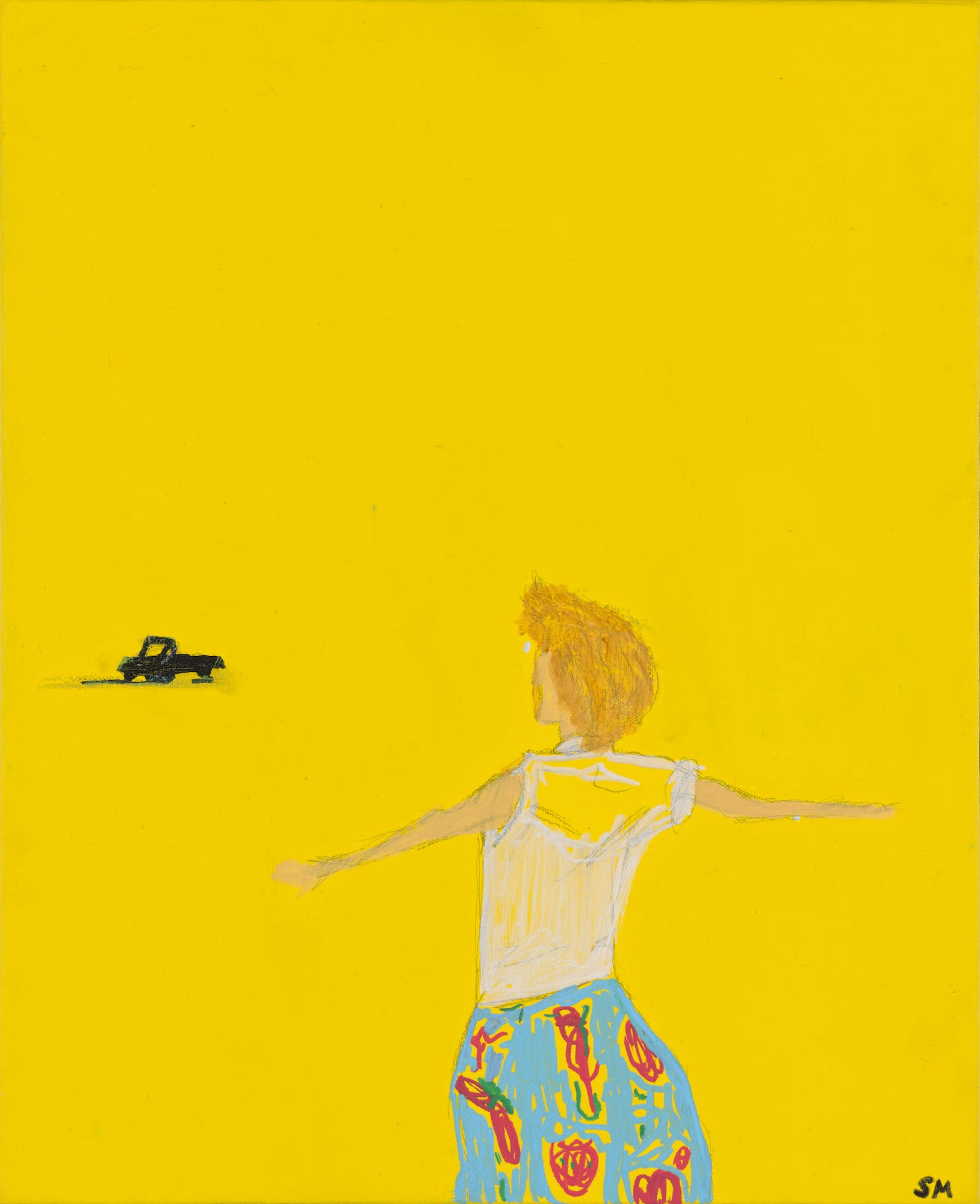

SM: The movie and the music in this piece are basically one thing. It’s quite unique, in my limited experience, anyway. Wim Wenders is admittedly a big fan of Ry Cooder and it makes sense watching it. I assume he did the music afterward but it’s almost like it was playing as they were shooting it–it’s that right. Some things were certainly reinforced after watching it. A big one is that you don’t need much to do beautiful things. I mean that. People have it in them–allow for space and things will bloom out of seemingly thin air. I try to honor some of that in my work, giving space to the subjects of my paintings. When I watch or listen to movies, music, whatever it may be, I like to daydream or wonder about this or that so I try to allow for that in my work, too–space.

FJ: Was there one Paris, Texas-inspired painting that started this whole project?

SM: The peep show scene near the end, which I recently found out was written basically overnight by Sam Shepard, who was remote to the movie by that time in the filming. They only had half the film written and then some delays caused Shepherd to move on to other projects. Wim pleaded with Shepherd to write the ending and that’s what he came up with. It’s brilliant. So that was the first image that I tried to do…and then I went where I had to go with it.

FJ: As a painter, how do you interpret a movie that is already visually stunning? What was your thought process like?

SM: Maybe it’s a luxury of being self-taught because I don’t have the same ability as some painters who could bang off perfect reproductions of scenes–so it does remove a lot in the way of options. Options can be momentum killers. That kind of allowed me to take the emotion of it all, then sit with it and try to reproduce it all on the canvas.

I would watch the movie a bunch of times and write down words or ideas as the film went along. Eventually, it was becoming too obvious, so I started doing some research on Wim Wenders and discovered his books on the American West. From my understanding, he would shoot a lot of photos on scouting trips and I found what I believed to be research that was done in preparation for Paris, Texas. In any event, they certainly gave me that same chill that the film does. I then used these as the back half of the project, and I really liked how it turned out.

FJ: What inspired you more, the music or the movie as a whole?

SM: I can say that without the Ry Cooder affiliation, I may have never watched this movie–certainly not with the same intention. My dad has been a huge influence on me, music-wise. He’s a legit audiophile and these songs and many like them have been played since I was a kid. So I guess I owe it to him for bringing me up on his (Ry Cooder) music and others like him. You can talk for hours about Ry Cooder and never get to the heart of it. The music is really what does that.

Once I watched the film, everything started to matter just as much as the next. The characters, the actors that played them, the cinematography (Robby Müller), the locations they shot in, and eventually Wim’s own research in the West.

I’m glad you asked this question because this is certainly an instance where everything works in absolute harmony and one can’t exist without the other.

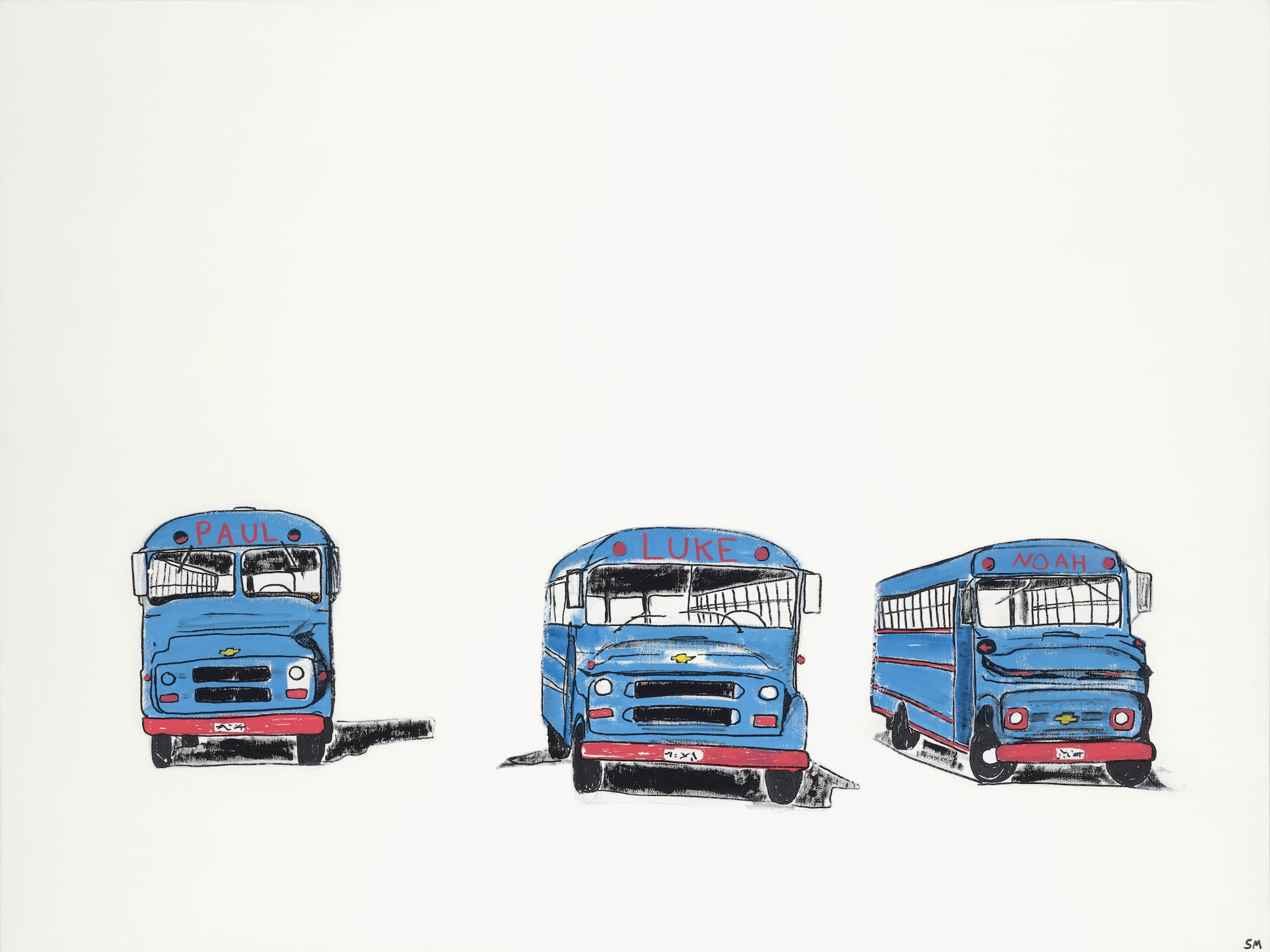

FJ: For those who can’t make it, walk us through the gallery and the collection of paintings you’ve assembled.

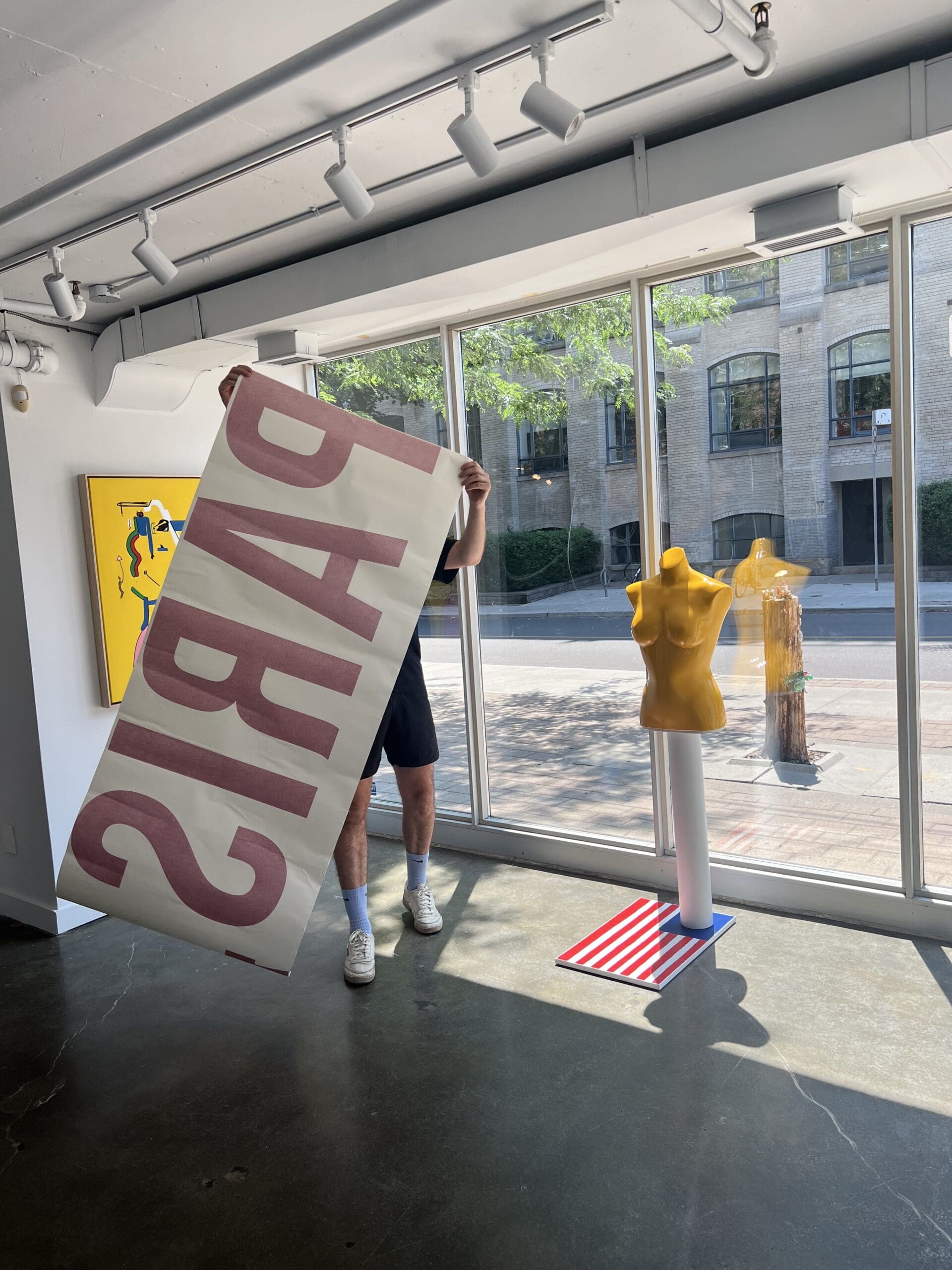

SM: The gallery is located on Queen St. West in Toronto and has floor-to-ceiling glass windows that allow the light in, as well as the pedestrian traffic to see exactly what’s living inside. It’s a busy area and has a strong history of creatives living and working nearby so it feels like a welcoming place to display such an exhibition. I used the large glass windows to display the title of the show, Paris and Texas each having their own 8-foot-high window. An outline of the “Blue Face” (the lone ceramic piece in the show) also occupies a large window area. Big and bold was the idea for the windows, almost billboardesque.

From the street you see an old yellow Toshiba TV on a white homemade plinth with a hidden VCR inside that plays the movie throughout the day and night (rewinds are needed, of course). From the window on the other side of the gallery you find a yellow mannequin bust perched atop a white (painted) PVC pipe on a piece of wood adorned with a painted American flag, albeit without the stars. Inside the gallery you’ll find the ten paintings, one ceramic piece, and the two installations mentioned above that constitute the exhibition. Sandwiched between two pieces is the statement below:

Paris, Texas is not so much a place but a way of remembering the past. Moving through frames rich in colour, light, and intent, cradled by the hollowed-out sounds offered up by Ry Cooder, Wenders and Shepherd gave us a lasting record of what time looks like. These paintings come from the endearing impression left behind by the images themselves and perhaps more, the emotion that accompanies the visual and auditory memories we keep. As the line between dreams and our subjective reality becomes less clear, we are well advised to stop counting time by the clock and instead do what Wenders did, let the story become time.

FJ: What’s next for you after this?

SM: That’s hard to say because right now I still feel like I’m smack dab in the middle of this one, with it just being installed. I’ve been working on a couple of projects related to it like clothing and some fine prints so maybe once it’s all settled down, I’d like to get back to recording music, namely an instrumental record I’ve been writing. I also recently bought a fiddle, and my brain is trying to make sense of the fretless world, but I’m really excited about it.

There’s been some talk of collaborations with other painters which would be a first, so we’ll see what happens.

Learn more about Milne’s exhibition: The Lyceum Gallery Paris Texas. You can also follow the artist on Instagram.