Rick Turner was a polymath: A professional musician, an inventor, a luthier, and an electronics wizard. And yet he was also one of the most approachable people in the world of music. For so many instrument fanatics and builders, he was a resource whom we could count on. His own instruments helped thousands of musicians – famous and obscure – sound as good as humanly possible. All the while, he helped innumerable builders (even his competition) become better at their craft with free advice and help. Obscure Vivi-Tone guitars from the ’30s, tooling, pickups, bass construction? He knew it all.

Turner passed away on April 17, 2022 at the age of 78. It seems unfathomable that someone who was always there for our little community – on the phone, at trade shows, in online forums and social media – is gone. Having outlived so many of his rock & roll peers, he almost seemed immortal. Thankfully, we still have his designs, guitars, basses and ukes to ponder.

Rick lived through so much music history and his memory was as sharp as his chisels. He was a fixture in the Cambridge music scene, playing for Ian & Sylvia. With his trusty D-28, Turner backed the duo at clubs around the country and at Newport in 1965 (the same year Dylan went electric!). That same year, he personally installed a 6 1/2 fret on Richard and Mimi Farina’s dulcimer. This is standard fare on many dulcimers built today, but he did it first.

Just a couple of years later, he went electric himself with the band Autosalvage. The NYC-based group was signed to RCA and put out a self-titled record in 1968 (give it a listen here on YouTube). Perhaps if they were based in California, they would have made in-roads, but their debut fell flat with the East Coast crowds (though they did get to open for Richard Pryor once at the Cafe Au Go Go). As with so many bands ahead of their time, today the album has a bit of a cult following. It’s since been reissued and original copies fetch good money on Discogs.

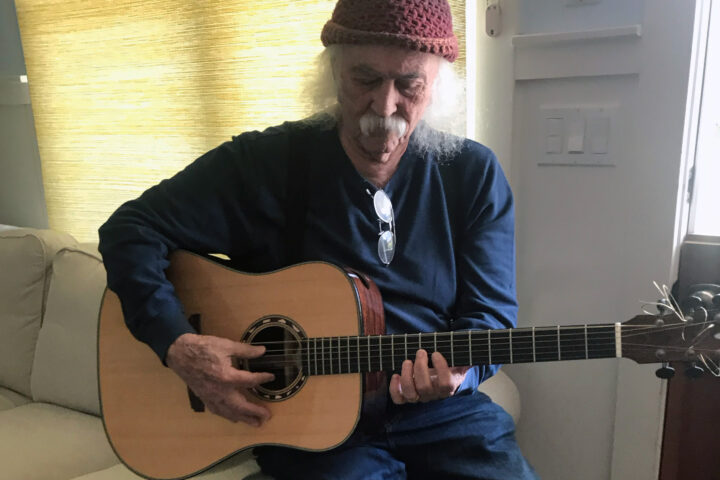

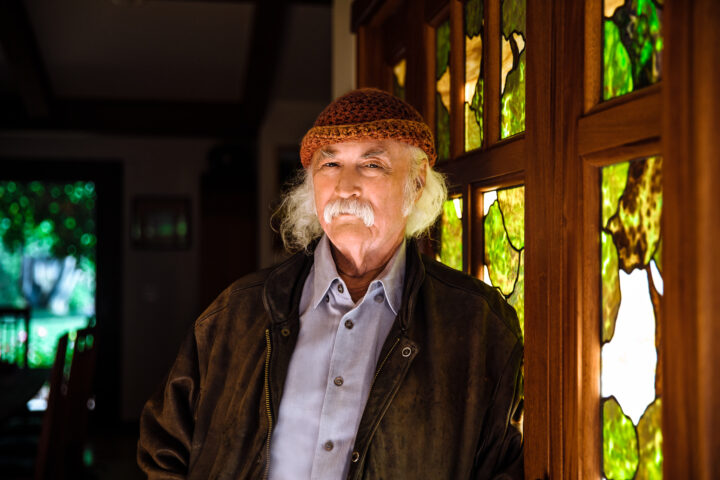

Leaving that group, Turner moved to California and, in 1970, found himself at Alembic alongside Owsley “Bear” Stanley, Ron Wickersham, and Bob Matthews. There, he handwound pickups, designed guitars and basses, and was on the frontlines for the Grateful Dead’s McIntosh-powered, 125,000-watt Wall of Sound experiment. You’ve undoubtedly seen or heard his creations or mods from this era: the Dead, the Youngbloods, Hot Tuna, the Mothers of Invention, and numerous other acts of the ’60s and ’70s had custom Alembics. Jack Casady still plays his Alembic, as does David Crosby. Rick and I were once emailing about amplification and pickups and he wrote: “I only wish Garcia and Owsley were still around to discuss this shit with. They understood this stuff. That’s why they took me into that circle in 1969. To both of them, I was a guitar player who took a left hand turn into lutherie; they knew exactly where I was coming from.”

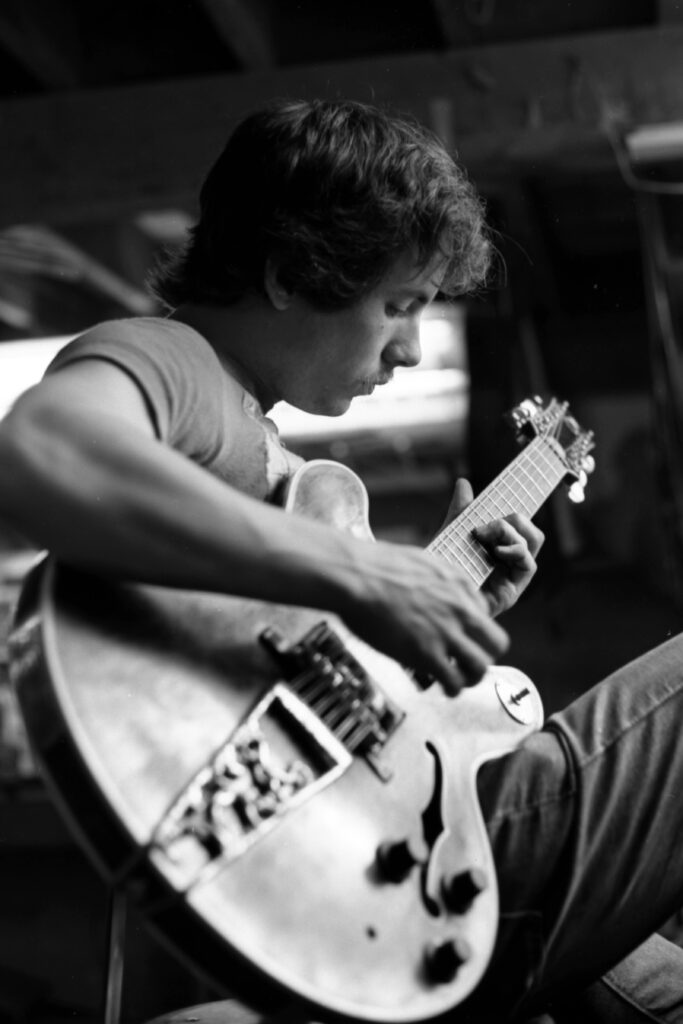

Turner playing David Crosby’s 12-string for the first time at Alembic. It’s a Gibson Crest thin hollowbody with a solid Brazilian rosewood neck made by luthier Mario Matello. Turner crafted the bronze tailpiece, the Alembic peghead inlay, and the true stereo humbucker pickups. LED position markers were inlaid in the fingerboard binding. David Crosby still uses this guitar today and everything still works, even the LED markers. Photo: Gary Somberg, reprinted from Fretboard Journal #25.

Turner worked at Alembic for nearly a decade until he set out on his own in 1978. One of his first creations was his Model 1, an electric guitar inspired by the shape of his 1820s Stauffer guitar. This is Turner in a nutshell: A guy who knew enough about the history of musical instruments to go back 160 years and find a design that, with a cutaway added, would be the ultimate electric guitar shape. (Later on, he’d often sing the praises of the architecture behind quirky Howe-Orme instruments, also from the 1800s.)

The Model 1 was quickly embraced by Fleetwood Mac’s Lindsey Buckingham, who bought the second prototype, took it on the Tusk tour, and tirelessly has used it ever since. If you want to rock your world and see just how involved hand-made guitarmaking is, check out the gorgeous drawings that former Turner apprentice Barry Price did (PDF link) on the assembly of a Model 1.

Turner’s career was not without its twists and turns. The early ’80s were lean and he got into cabinet and furniture making. On the side, he did some consulting work for larger guitar brands. In 1988, he took a full-time job at Gibson as their West Coast Artist Relations Manager. It’s hard to imagine this arrangement lasting long; Gibson’s turnover was pretty notorious back then and Turner was never one to compromise. He once told me a hilarious story from this era about the time he pitched Chris Thile to the Gibson corporate brass for an endorsement deal. Chris was a mere eight years old at the time. “I thought he was the future of the mandolin,” Turner said. “Hey, what the fuck did I know? Well, the boss men thought I was out of my fucking mind to propose signing an eight year old kid. No, I needed to study the Billboard ‘Top 100′ charts and go for them.”

Though he did sign Guns N’ Roses and various other acts who weren’t still in elementary school as Gibson artists, Turner always considered himself a guitar designer first and foremost. He’d spend hours working on piezo pickup designs and acoustic amplification. When Gibson ignored many of his design pitches, he struck a deal so that he could keep the designs they didn’t want to produce (his Electroline bass was one such model). He’d eventually move on and do repair work at Fred Walecki’s Westwood Music, fixing the guitars of many of his old Alembic clients, as well as guys like Jackson Browne and David Lindley. He went even deeper down the piezo pickup rabbit hole.

Inspired by his connections with Browne and former Alembic client David Crosby, he helped develop the Highlander pickup. Around this time, there was a renewed interest in his Model 1 guitar and he started building those again, too. Bill Asher of Asher Guitars worked alongside Turner for a while, honing his chops doing repair work while Turner built new instruments. In the mid-’90s, Turner would move to Santa Cruz and become a fixture of that area’s thriving lutherie scene.

Turner was truly a jack-of-all-trades: Restoration work, new electrics, new acoustics, amplification, basses and guitars. His Renaissance series of instruments combined his passion for both acoustic and electric instruments. He got into digital signal processing and even had a side business with Seymour Duncan, D-TAR (short for “Duncan-Turner Acoustic Research”), where he helped design acoustic pickups and pre-amps. “What I learned about guitar making and pickup design was driven by my own frustrations as a pro player,” he once told me. “Another subject that keenly interests me is how much I learned about acoustic guitar design from the D-TAR Mama Bear project, where I had to think incredibly deeply about just what an acoustic guitar body does to the string signal to create a signature sound. I may have learned more from the thought process of figuring out how to create a digital model of the signal transform than I had in close to 50 years of tapping on tops… and that has now affected how I view making fully acoustic guitars.”

Turner continued, “What is the signature sound of an acoustic guitar? It’s a fucked up mess… which we find utterly compelling. Why? Because the physical limitations of wood and air transform a relatively simple audio signal into something vastly more complex. It’s 3-D EQ. Frequencies, levels, and time smear.” (In the spirit of full disclosure, I think at this point I knew my email conversation with Rick was going way over my head and I didn’t dig much deeper. I regret that now.)

When ukuleles boomed in the 2000s, Rick Turner was there, too. You’d see this rock and guitar legend – one of the last keepers of the Grateful Dead’s Wall of Sound secrets – at uke festivals and club gatherings selling his new Compass Rose line of ukuleles. He truly did it all.

I suppose the one constant with all of Turner’s output – the legendary Alembic Pretzel, the Model One, his Renaissance Steel, and even his ukuleles – was his dedication to sound. Turner made unconventional looking instruments, shaped by sound. They weren’t designed to look trendy or cool or sell at the big box stores, they were designed for working musicians who wanted to sound as great as possible. And, as the technology evolved, so did his creations.

Last, but definitely not least, one can’t overstate Turner’s contribution to the rest of the guitar community. All the knowledge he had – whether it was about under saddle pickups, bracing, Jack Casady’s Alembic, Jerry Garcia, or anything else – was open source. You merely had to ask. Luthier Jason Kostal wrote, “He loved to make people laugh and was great at helping people realize their mistakes were not as catastrophic as we usually believe…. most of all he was always there for a late night phone call when I needed help.” That sentiment was echoed by dozens of other great builders today on social media. He never viewed fellow luthiers as competition; he was always there.

More than a few of us civilians also experienced this, too. You’d start a thread on Facebook or a guitar or bass forum only to find the subject of the post (Rick) chiming in with his own color commentary. “Is that the Rick Turner … responding to my little Facebook question?” Yep, and it happened a lot. It was one of the many things that made our little universe, and Rick, so unique.

RIP, Rick. We’re going to miss you.

Below: Turner with Jack Casady at the 2016 Fretboard Summit. Photo: Tim Whitehouse