UPDATED: When we spoke to Andrea and Alessio at the start of 2017 they were moving into their new workshop, but it was still too soon to share pictures or tell us much about it. Here at the end of 2017 it seems a perfect time to check back in to see how things are going and get a look at the new shop.

If there’s one thing the guitar community can build a consensus upon, it’s identifying the Salad Days of acoustic flattop guitar making. Be it Banner, pre-war or “Golden Era,” the instruments built by Gibson and Martin during the ’30s and ’40s are the standard to which all those who follow will be compared. Naturally, more than a few of those who’ve followed have decided to go to great lengths to recapture the magic of those guitars. Over their twenty-plus years in lutherie, Italy’s Andrea Bagnasco and Alessio Casati seem to have come as close as anyone, so it’s about time we subjected them to the Bench Press treatment…

Alessio Casati (left) and Andrea Bagnasco in their new workshop with a bit of inspiration.

Fretboard Journal: What’s on your bench right now?

Bagnasco & Casati: Right now we have some leftover guitars from the 2016 batch that need to be completed and shipped and some tops and backs for the 2017 batch. We ran a little late with the 2016 batch since we have long been in the painful process of moving the workshop. Hopefully we’ll be done with it by January 2017 and be able to get back to full speed (or even increase speed some). We have to finish lacquering the following guitars (we’ll finish spraying lacquer in the new spray booth):

- Two ‘910 model’ Southern Jumbos (i.e. with old stock East Indian RW back and sides);

- one J-45 with three-piece poplar neck;

- and one 12-fret ’34 style shade top D-18.

We’ve also started working on the following instruments:

- A couple of ’37 (i.e. forward shifted x brace, no popsicle, 1 3/4″ nut, etc..) D-28s (one natural, one shadetop) with Madagascar rosewood back and side;

- one ’37 style D-28 with Brazilian Rosewood back and sides;

- a couple of ’37 style D-18s;

- and one Advanced Jumbo with old stock East Indian RW back and sides.

Concerning repairs, we just finished three interesting guitars: a couple of Martins from the ’50s and an early ’60s Epiphone Troubadour. The latter is basically a 12 fret, square shouldered dreadnought with maple back and sides with a big boomy sound that retains a lot of clarity. It sounds quite peculiar and very musical. It doesn’t come from the Golden Era, but it’s built nicely and it has vintage character. Those guitars were made at the Gibson factory, sport ugly flamenco-like white pickguards and a nearly unplayable (for our own taste) wide and flat neck. They usually have a severely misplaced bridge plate, like if a 14-fret body was used for a 12-fret guitar, so the string balls rest on the spruce top instead of the maple plate. Anyhow, after we reset the neck, the guitar sounded great!

As for the Martin guitars, the first is a ’53 D-28 that was converted to style 45 in 1963 by the late mandolin maker Bob Givens. We straightened the neck by compression re-fretting. This technique has not only an impact on playability, but can change dramatically the way the guitar sounds, as it stiffens the neck where it’s most important (on the fretboard surface). As a result the guitar sounds more focused, has a stronger fundamental, better clarity and possibly a quicker note attack. We compression fret all of our B&C guitars.

The second is a ’55 Martin 000-18, that came in the shop for a (compression) refret and a neck reset. Often times, Martins from the ’50s will really benefit from a neck reset and a bridge re-glue. While they’re still well made and well designed guitars, workmanship isn’t quite the same as on earlier Martins, so a bit of TLC goes a long way in bringing them up to their full potential.

FJ: How did you get started?

B&C: That was long ago, back in 1995 when we decided that we had too refined of tastes for guitars than what our just-out-of-college-student pockets could afford. Alessio was already good with woodworking so we decided to buy a couple of books via mail order (there was no internet back then), scout for all the information on steel string guitar building that we could possibly collect (not an easy task in Italy in the mid ‘90s) and give it a try. I remember driving my old Fiat 500 up past Milan to a wood dealer to buy our first sets of everything. We got some Red spruce of average quality, African mahogany and ebony to get started on our first two guitars. We went for a slope shouldered dread sized design, although these had nothing to do with the Gibson replicas that we build today. It took us almost a year to finally put strings on these guitars – they must still be around somewhere.

FJ: Tell us about your shop…

B&C: We are just moving the workshop to a new, bigger, better place! Not far from where we spent the last four years–it’s still in Savona, Italy, on the Ligurian coast. The old workshop has become way too small to keep up with business. We are planning to involve our customers and aficionados in general in the move–we’ve been out of the social radar lately but we’ll catch up by sharing photos and videos (maybe some live events?) in the new place. The cool thing about the new workshop is that it’s facing the railroad–just a few yards away from the rails. The old Gibson factory in Kalamazoo used to be next to the railroad, so did the Fender factory in Fullerton. I’ve read that the first Fender employees actually had to cross the rails to go to the restrooms. Fortunately, we have a restroom in the new workshop so we won’t have to go out and cross the rails. Still, we’re hoping that some railroad mojo that made Gibson and Fender great will soak its way into our B&C guitars!

FJ: What’s your philosophy on wood and materials?

B&C: Great ingredients are the basis for any great dish. When you have great ingredients you can build on a great design and with great craftsmanship you can hope to end up with a great guitar. We try to source the best wood we can find–we’re particularly concerned with the spruce that we buy. We try to buy direct from the loggers as we look for moon-logged and air dried spruce only. The more middle men between the logger and the buyer, the less you can be sure of what you’re actually buying. Some wood has become a pain to source, being so hard to find and the bureaucracy involved heavier by the day. Some timbers have almost become impossible to buy and resell–this has gotten actually quite serious. We’re afraid a time will come soon when it will simply be unpractical if not downright impossible to build with certain rosewoods, for instance. We’ll all have to deal with it: both builders and players.

Going back to materials in general, we like to stick with the tradition–even if using real celluloid and nitrocellulose lacquer is a lot more inconvenient and time consuming than using modern plastics and water-based poly finishes. Concerning glue, we only use hot animal hide glue, but for once the old stuff is way better to use, more practical and pleasing to work with than modern glues. We feel these old materials make for better feeling and sounding guitars and are definitely worth the effort. Plus, most of our clients happen to be vintage guitar owners and collectors. They appreciate a new guitar built traditionally. And so we do, too.

FJ: What is it about those “Golden Era” Martins and Gibsons that you are drawn to?

B&C: Anyone familiar with these guitars will know exactly what we’re drawn to. These are the guitars that defined the way good guitars sound, they are the pinnacle of the steel string guitar design and craft. There was no such thing as industrial guitar production back in the ’20s to ’40s. Have a look at Martin’s shipping totals in the years from 1925 to 1975: it’s an exponential curve and it gets steep right about 1964, when the acoustic guitar demand grew like never before in history. We need to blame the Beatles for that, I’m afraid… but anyhow, the so-called “Golden Era” Martins spanning from 1929 to 1939 are just a handful of instruments, compared to any yearly production of more recent times.

These were times when good craftsmanship was commonly found. People had a natural dexterity in doing things–the majority of jobs involved practical intelligence and manual ability, something that has long been lost. Just think about the fact that some of the most highly regarded Gibson acoustic guitars were produced at a time when the Gibson factory was run almost entirely by women, during World War II. I think most of us here are familiar with our good friend John Thomas’ book Kalamazoo Gals about wartime Gibson production and the workforce of untrained women that manufactured the banner guitars.

Also, materials commonly available for guitar building were undoubtedly better. Some of the premium quality Brazilian rosewood that was used on Martin guitars during the Golden Era is simply no longer available. Right now, sourcing the right wood to build in true golden-era style and quality is a daunting task. So in the end take great raw materials, a great design and match it with old school guitar making techniques that could rely on the natural dexterity of the workforce and practical intelligence handed down from generation to generation–the end result is an outstanding product. This is in our opinion the true magic behind the Golden Era instruments.

FJ: In your opinion, how important is a guitar’s weight?

B&C: We like light guitars. There’s a right amount of lightness that needs to be achieved, where there’s nothing in excess of what is strictly necessary to make the best sounding guitar with the most volume and good structural stability. If you push it even further then the lightness gets overdone and the guitar might suffer in sound, where you might end up loosing the fundamental of notes, or stability. In the end, it’s also a matter of personal taste and playing style. Some ’20s Martins and Gibsons are, in my opinion, too light for steel strings and modern playing techniques. Put a light set of strings on a delicate early ’20s Martin and you’ll choke the guitar, regardless whether it will survive the tension in the long run.

FJ: How has your repair work influenced your own builds?

B&C: Direct experience on vintage guitars has been something that we could never have done without. You can’t build a vintage replica if you don’t have direct experience with the real thing, no matter how many books you read on the subject or the blueprints and measures that you follow. There’s nothing like putting your hands on the real guitars, sticking your nose in the soundhole, feel the instrument, spend time with it. Every old guitar that ends up on your bench for repair is a terrific opportunity to learn something new.

FJ: Do you have a favorite guitar that’s crossed your bench? Or a repair that you are most proud of?

B&C: There were many favorites. Not a specific model or vintage or brand: sometimes vintage guitars have a magic factor. There’s no way to predict it, but our experience is that unmolested guitars, those that were never modified, even the heavily played and beat ones, when properly taken care of usually sound the best. They can sound anything from great to incredible. The incredible ones are few and far between but when you stumble upon one of those, you notice immediately. Bringing these guitars back to perfection is the most rewarding experience in guitar repair.

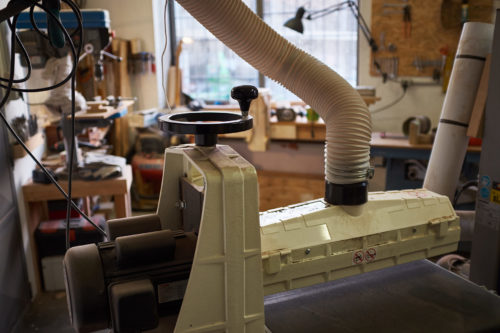

The New Shop

FJ: How’s the new shop working out?

B&C: The new shop is working out really well so far. The move took longer than we were originally hoping for, but in the end it was well worth the effort. For one thing, it’s much larger and with better natural light than the old one. Then, we were able to finally have separate, segregated areas, which is of utter importance.

Now there’s a clean room that is also climate-controlled all year round, which allows us to keep RH [Relative Humidity] where we need it pretty much regardless of the season. Here we do all the repair work and all the activities done by hand, which is still the vast majority of what goes into the making of one of our guitars: glueing, chiseling, planing, jointing, sanding, etc. Wood is also stored in this room because of the climate control.

Then we have a “dirty” area where we keep all the heavy machinery (table saw, routers, thickness sander, drill presses, etc.) and the related dust that escapes the suction system. Opposite to the dirt room, on the other side of the building, we have our spray booth. This is probably the single most important upgrade vs our old workshop. It’s large, well-lit, with good ventilation and a suction system that works. We have long been needing something like this. Finally we have a fourth room where we keep all guitar cases and the buffing wheels. It’s such a pleasure to work in the new place and it’s also a place where we can finally welcome our clients in a clean, tidy environment, sit back a while while we discuss things, enjoy guitar talk and the wood and hide glue scent that’s in the room. It’s just a place that speaks love for guitars…

FJ: Has it changed how you work?

B&C: Yes, it has. For one thing, having a nicely equipped spray booth in house allows us to work on smaller batches with the aim of keeping the booth busy all year round. There are certain things that we still like to do during the wintertime, despite the climate control, such as top and back bracing, but for the later steps of the building process, being able to spray all year round allows us to break the ‘old’ yearly batches down into smaller batches of just a few guitars that we can work on at the same time, from lacquer spraying to final assembly. This makes things easier to handle as we can chew our way forward in smaller bites, so to speak, vs the old way of working that wanted us to push forward all the guitars due in one specific year at the same time, because we had to target specific times of the year to do certain tasks, spraying lacquer in particular.

Also, speaking of finishes, we’re finally in the position of working on continuous improvement of this specific part of guitar building, which is also probably the most delicate in our opinion. We are fine with a well-applied, pure nitrocellulose, modern-looking glossy lacquer finish, but we’re very familiar with the finish of fine vintage guitars, early 30s Martin especially, and those are the finishes we love and that we aspire to.

Then of course, working in a better-equipped, larger, better-lit and more welcoming environment just makes life better.