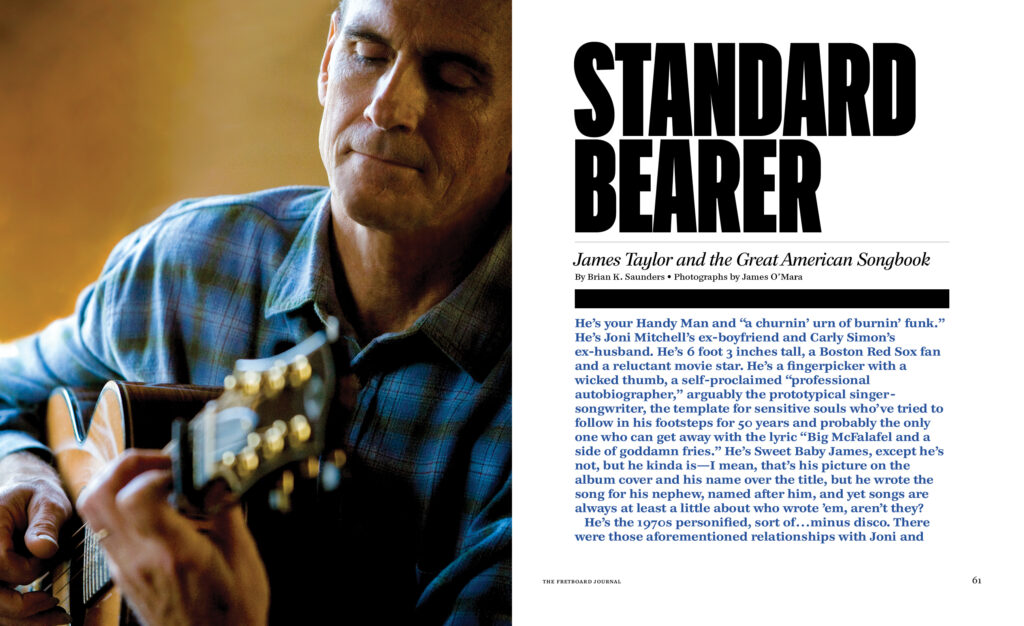

James Taylor is a folk singer. He’s a troubador, a balladeer and a soul man. He’s a rock star. He’s your Handy Man and “a churnin’ urn of burnin’ funk.’ He’s Joni Mitchell’s ex-boyfriend and Carly Simon’s ex-husband. He’s 6’3” tall, a Boston Red Sox fan and a reluctant movie star. He’s a fingerpicker with a wicked thumb, a self-proclaimed “professional autobiographer,” arguably the prototypical Singer/Songwriter, the template for sensitive souls who’ve tried to follow in his footsteps for 50 years, and probably the only one who can get away with the lyric, “Big McFalafel [sic] and a side of goddamn fries.” He’s Sweet Baby James, except he’s not, but he kinda is — I mean, that’s his picture on the album cover and his name over the title, but he wrote the song for his nephew, named after him, and yet songs are always at least a little about who wrote ‘em, aren’t they?

…

[In the midst of a pandemic] James is apparently busier than he would have been had his tour not been postponed, but somehow he found time to talk with me on the phone. I’ve calmed down a bit, my expectations tempered. I’ll take what I can get here. We talk over each other as we extend our greetings, then I take a deep breath, both to calm myself and to leave some space for James. He asks where I’m calling from and, after I tell him I’m in Seattle, he lowers his voice ever so slightly, sliding gently into Storyteller Mode:

I’m in Rhode Island, on the Narragansett Bay. We’re looking across at Fort Adams, where the Newport Folk Festival was held, and where I’ve performed a number of times…

And then we got to talking.

FJ: Can we start by talking about how you first picked up the guitar? Who were your earliest influences?

JT: Well, it was during what my friend Waddy Wachtel used to call “The Great Folk Scare of the early-1960s,” which was a great thing for me and for all guitar players, really, guitar singer-songwriters. It was a return to a very basic kind of music that could be played with just guitar and voice. It was accessible. That’s what “folk music” basically means to me: It doesn’t have a formal component, a formal training component like classical music, and it’s accessible to people. It was a great time to be learning to play and to be performing live, beginning a sort of performance style, finding your way. I was influenced by people like Tom Rush, the Kweskin Jug Band — I don’t know if you know about Jim Kweskin’s Jug Band, you gotta check them out, you gotta listen to them — the Charles River Valley Boys, you know, typical Dylan and Baez, Ian and Sylvia, early on the Kingston Trio — my brother brought those records into the house. I sort of lived in that musical world for a while, but [he?] my older brother also brought home rhythm & blues and chitlin circuit music from when we lived in North Carolina — you know, Don Covay and Joe Tex, the Coasters and the Drifters and Ray Charles. I got a very strong soul component early on, and that entered into it. And when I met my friend Danny Kortchmar, he was fifteen and I was thirteen, and he loved the blues and he taught me what he knew and really sort of got me infected with it — Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Lightning Hopkins, Little Walter, Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters, but also what we think of as “country blues,” in the Robert Johnson kind of tradition. That was in my early teens.

…

FJ: You developed a very singular and identifiable style, and it extends even to the way you play your [first position] D and A chords, with your index finger…

JT: …playing the third. Well, that allows me to hammer on and hammer off more, like in “Country Road.” I always play in G, E… D and A. Those are my favorite, very rarely in C fingering, although that was the first one I learned. G, E, A and D are my go-to keys, and in order to make whatever I’m playing comfortable I’ll use the capo on the first, second or third fret, and very rarely on the fourth fret. The reason I play those sort of inverted-sounding As, Ds and Es with [index] finger playing the third and hammering off like that is because when I was learning the chords I didn’t have any instruction, so I’d be playing along in C and I knew I needed a IV chord and I realized what the bass of it was, just an F, so I’d play an F and I’d find whatever on the next highest string harmonized with that bass note. So, I heard the chords first and then I found them on the guitar, but nobody told me where to put my fingers so I just made that A chord and the D chord turned around like they are, and that really made a huge difference in how I play.

I think the other thing is that, from the beginning I finger-picked and I was always playing a bass line with my thumb, which kinda drives my bass players crazy, because they have to either stay away from that or play it exactly.

…

Taylor’s Olson #1 (left) and #2 (right), both SJ (Small Jumbo) models with cedar tops and Indian rosewood backs and sides. Photo: Jim Olson

FJ: When I think of how you sound on guitar, I don’t think of old guitars. I think of these very present, brighter instruments that James Olson builds for you.

JT: I have a pretty clear and simple history of my playing. There was that first, cheap acoustic nylon string guitar, followed by a Gibson that a family friend lent to me, and then I bought my own J-50, and I used that for my first three albums. Then I went to a handmade guitar by a guy named Mark Whitebook and I lost that guitar in a divorce so I wandered around for a while — I played a Takamine, I played a Yamaha custom — but eventually I went to do a benefit in Minneapolis and a guy named James Olson got a guitar into my hotel room, and as soon as I played it I’ve never looked back.

FJ: He makes wonderful instruments…

JT: He really does, and part of it is that he invented a system for building them, they’re definitely handmade guitars but they’re so consistent. They’re so reliably good.

…

FJ: John [Pizzarelli, who played guitar on and co-produced Taylor’s latest record, American Standard, with Dave O’Donnell] told me he just couldn’t play your guitar, he couldn’t keep it from buzzing with the action that low…

JT: Huh. That’s right. You know, playing that 7-string guitar, he’s definitely got Popeye the Sailor’s left hand.

FJ: Because you like such low action, when you’re touring does JP [Jonathan Prince, Taylor’s guitar tech] have to tweak your guitars daily to keep them in that spot where you like ‘em?

JT: Yep. I mean, it’s not daily. He’s checking on them daily, and very aware of what they’re going through, in terms of humidity and heat. And he’ll say to me, “I think the #2 guitar is beginning to buzz just a little bit, how do you feel about me releasing the neck a little bit?” There’s a constant discussion about it, but he isn’t changing it that often. He’s always got it in mind. It is difficult for a guitar tech — and JP delivers that, he changes strings daily. When we’re on the road, every night we play we’ll need a new set of strings. I sort of like that “new string sound,” those overtones on the bass strings. I have a tuning — I think there’s a tutorial about it on my website — sort of a tuning philosophy that basically tempers the guitar. The high strings are relatively sharp (only by a couple of cents, obviously) and the bass strings are flat, partially because the bass strings ring high when you hit ‘em, partially because I use a capo, and that tends to pull things sharp, particularly the bass strings. The other thing is that, if you have a wide-spread tempering — in my case the low E string will be nine cents lower than the high E string — that also forgives out-of-tuneness, the same reason it works on the piano. It opens it up and is much more forgiving in terms of playing different things in different keys.

FJ: You got to play with Ry Cooder on [October Road]…

JT: Yeah. Ry played on the title track of the album. That was a brilliant session; I’ll never forget it: He brought his Standel amplifier and a few guitars with him. What he put on that track… it was an overdub session and we just ran the track and said, “Play whatever you feel.” It was just a wealth of stuff for us to pick and choose from. That was my one time actually working with Ry.

FJ: Did you first meet John during those October Road sessions?

JT: I went to hear him play a number of times. I knew him through other friends. I guess the first time I ever worked with him was on the album October Road; he played on a song called “Mean Old Man,” which is really like a standard. It’s like from a different time.

…

[When] it came time to make this standards album, to do these songs that I had all these arrangements of, I just wanted to run them by John — I wanted his input, I wanted his take on the tunes. So, just in the process of showing him my arrangements of these songs we fell into a thing where he, with his 7-string — that bass aspect, that bass dimension to his guitar playing — he just supported my arrangements so well, and broadened them, and filled them in. I couldn’t have worked with a better person for a guitar standards album.

Taylor and co-producers Dave O’Donnell and John Pizzarelli working in Taylor’s studio. Photo: Ellyn Kusmin

We cut all the basic tracks in about two weeks, with just two guitars and vocal. Then we spent a lot of time working on the vocal performances themselves, and then I went around to my usual musical community, which is my band plus a couple of players in Nashville: Stuart Duncan and Jerry Douglas and Victor Krauss, playing fiddle and dobro and bass. I went to my band and those guys in Nashville and my singers and, just added things to it. I added some percussion from Luis Conte; Steve Gadd heard drum parts on a couple of the tunes and he has that ability to play to a track and sound like he was not only there at the beginning but driving it, you know?

I didn’t put any keyboard on the album, because I wanted it to be about the guitar and the guitar arrangements. I just wanted it to be me and John.

FJ: It’s surprising to realize that your albums have been so built around piano-based arrangements, when you’re an iconic “guy with a guitar” singer-songwriter.

JT: That’s right. You know, as soon as you go to a piano player, and particularly an excellent one, a master like Larry Goldings or Don Grolnick or Jeff Babko or Jim Cox…once you go to a piano player like this and teach him the changes, it’s almost like the guitar disappears, because there is a guitar at the center of all of my songs, because they’re written on the guitar and the arrangement is first iterated on the guitar, but when you run it through the band, basically it becomes invisible. I really wanted to keep the guitar at the center of all these arrangements, and I feel like we did.

Editor’s note: These are selected excerpts from our lengthy cover story in the Fretboard Journal #47. Order a digital or print edition and you can read the feature in its entirety, plus conversations with luthier Jim Olson and engineer/co-producer Dave O’Donnell.