Guys like J.J. Cale (and Townes Van Zandt, Eric Von Schmidt and Mose Allison, to name a few) have always defined solid cool for me. They had something the likes of Eric Clapton, the Rolling Stones, Van Morrison and Bob Dylan all dug and brought to larger audiences. Yet those audiences still haven’t figured out that these “obscure artists” really deserve the kind of attention and accolades they reserve for big stars. Maybe someday…

Although I never quit listening to his records, the last time I saw J.J. Cale, he was playing a double bill with John Hammond at the sadly defunct Bottom Line in New York sometime in the mid-‘80s. He was touring the country from California to Maine, with a few dates in Canada, but not for the sake of promoting a new album. The man hadn’t recorded in over three years. His most recent LP at that point was 1983’s Number 8. So why at this point in his career did Cale suddenly decide to pop out of the woodwork? It turned out the hip hermit was “on vacation.” Following his soundcheck, I interviewed J.J. in his tour bus, which was parked around the corner from the club.

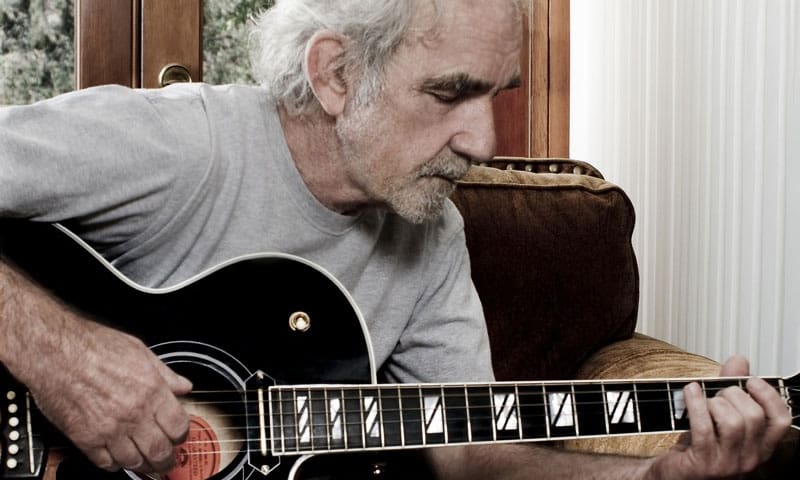

Cale began his set alone, strumming “After Midnight” on an Ovation acoustic. Singing in a snake-like whisper, Cale resembled a radical college professor for the 1960s in his crumpled cords, tortoise shell glasses and salt and pepper goatee.

“I live in a trailer park in L.A. And haven’t owned a phone for five years,” he said, with a devil may care grin. “That really shut my business off! I’ve been playin’ music for 35 years and I thought it was time to stop and smell the flowers. Taking a drag on a Marlboro, Cale continued, “What little hype I had was completely shut down for four years. I got tired of makin’ records. I decided to get up in the mornin’ and do nothin’ all day,” he chuckled. “Just watch the sun go up and down.”

Meanwhile, Cale paid the rent with songwriting royalties, with everyone from Eric Clapton, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Waylon Jennings, Jose Feliciano and Poco cutting his tunes. J.J. even made it to the AM charts himself with the unlikely swamp blues number “Crazy Mama” when his first album, Naturally, hit number 22 on the Billboard Hot 100.

“I’m a songwriter, not a performer,” Cale emphasized. “That’s not my thing, so I don’t tour that much. The only reason I sing is ‘cause I’m a songwriter. If you write songs and they have lyrics, you gotta do somethin’. I’ve made a pretty good livin’ mumblin’, y’know?” J.J. laughed. “About once a year, I play the West coast from L.A. to Vancouver for about thirty days. I’m amazed people come.”

After a couple of sparse renditions of old faves like “Clyde” and “Call the Doctor,” J.J. was joined by his band – the Everly Brothers’ drummer Jimmy Karstein, Christine Lakeland on keys and vocals and bassist Doug Belli, who provided the overly laid-back Cale with a much-needed, swift kick. What followed was a set of original slinky blues and Southern-fried shuffles, along with an occasional Muddy Waters and Ray Charles tune tossed in.

Cale’s sound, immediately identifiable and surprisingly consistent over his long career, has been a major influence on Mark Knopfler and Eric Clapton. Asked about their similarities in style, Cale shrugged his bony shoulders and said, “Hell I’ve tried to borrow from everybody. That’s how we all learn. You can imitate up to a point, then you gotta come up with your own thing. I always liked T-Bone Walker, B.B. King and Clarence ‘Gatemouth’ Brown. I finally met [Brown] after wearin’ out several copies of ‘Okie Dokie Stomp.’ He’s an original! He made some great records in the late ‘40s and ‘50s. I’m also a fan of Mose Allison and Bob Dylan. It’s hard to beat Dylan as a songwriter, whether you like him or not.”

Cale, born in Oklahoma City on December 5, 1938, started playing guitar at age eight. Growing up in Tulsa, he played high school dances and local clubs with boyhood pal Leon Russell until forming his own group, Johnnie Cale and the Valentines. They covered popular country numbers and played loose renditions of the R&B tunes which Cale learned off radio broadcasts out of Mississippi and Louisiana.

“Little Walter and Muddy Waters were really cracklin’ around ’48,” he said. “That stuff was really happenin’ with high school kids before Chuck Berry got big and rock ‘n’ roll took off. I started playing electric guitar around ’52… I was washin’ dishes in a drive-in and makin’ payments on a Les Paul.”

Eventually, Cale hit the road with the Valentines in tow and headed for Nashville where he tried his hand as a country singer for a hot minute before winding up back on the road again in the support band for Grand Ole Opry singer Little Jimmy Dickens.

By 1964, Cale, who considers himself “a drifter or carny at heart” was ready for a change. Breaking up the Valentines, he headed for Los Angeles with Tulsa friend/bassist Carl Radle. Upon his arrival, Leon Russell hired Cale as a recording engineer at his studio.

“I made my livin’ twistin’ knobs,” he laughed. “I was the guy with the beer cans and cigarette butts after the band left. I used to sit there, tryin’ to please everybody while six people told me how to mix the tune.”

Looking back at his scuffling days in L.A., Cale lit another smoke and grinned. “I lived out there through the peace and love deal. We – Leon, Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett, Jim Gordon, Carl Radle and Bobby Whitlock – lived in the same part of L.A. It was kinda like Greenwich Village with its folk movement. I tried writing songs, was the engineer for several studios and played guitar in lots of bad bar bands. I did anything to stay in the music scene.”

“Anything” included writing songs for and co-producing an album called A Trip Down the Sunset Strip, credited to a group called the Leathercoated Minds and released on the Viva/Fontana label in 1967. According to the Illustrated Encyclopedia of Rock, the album was “an atrocious piece of psychedelic opportunism.”

Cale remained in California for six years but “couldn’t get nothin’ goin’ on. I figured I’d had it. It was time to be a regular guy and get a job sellin’ shoes or somethin’.”

Disillusioned, he left the West coast and headed back to Tulsa, “only to wind up playin’ guitar in a hillbilly band.” While in California, between sessions for the Surfaris (“long after their hits”) and playing guitar for Delaney & Bonnie (“before they got big”), Cale cut some demos of a couple instrumental numbers he’d written, including “After Midnight,” with a few short, devious verses tacked on to it. He softly whispered the lyrics in his best James Dean mumble: “We’re gonna cause talk and suspicion… ” Cut as a single in 1965, Cale “couldn’t give it away. It didn’t impress my friends or nothin’. My mother didn’t even like it!”

Back in Tulsa in 1970, Cale was “driving to a gig one night and there was Eric Clapton singin’ ‘After Midnight’ on the radio! Somebody, either J.I. [Jerry Allison, Buddy Holly’s former drummer] or Carl Radle had a copy of that thing and laid it on him. The original was real fast and animated. Real Walt Disney soundin’. That’s what Eric copied and had a hit with.”

Cale’s life began to pick up as the song ascended the charts. “All kinds of people were suddenly callin’ me, sayin’ ‘Come to New York!’ ‘Come to Nashville!’ ‘Come to L.A.!’ It really opened some doors for me. I still have bread comin’ in from it.”

J.J. claimed he didn’t meet Clapton “until five or six years later, on my first tour of England. He came to the gig and we hung out. Then, we went down to the studio where he was cutting a new album. He played me a rough mix of [Cale’s song] ‘Cocaine.’ He had just cut it!”

“Cocaine,” which appeared on Clapton’s 1977 album Slowhand, (along with the Cale-inspired shuffle “Lay Down Sally”) was the second Cale original that Clapton scored a hit with. Both Eric and J.J. sang the tune in concert, even through the Reagan age of urine tests and anti-drug commercials.

“It’s not a pro-cocaine song,” Cale insisted. “It’s what I observed. It’s what a songwriter does… observes. What amazes me is that at this point in time, they finally come out and say we have a drug problem. We had a drug problem twenty years ago!”

Cale didn’t record his first album, Naturally, until he was thirty-two. “Eric helped me out a lot. Leon did, too. I guess the reason I made it was that people helped me out when they didn’t have to,” Cale said, not taking a lick of credit for his success. “Nobody would go for the record. We shopped it around to several labels until Leon and his friends at Shelter Records put it out. They were surprised it went anywhere.”

Many of Cale’s records were recorded at his Crazy Mama studio in Nashville and drew heavily from Delta Blues and Appalachian mountain music for its inspiration. “The South has strong roots,” he said. “The musicians on most of my albums are from the South. I’m basically a frustrated banjo picker.”

His guitar style was rather unorthodox. While his right hand half-picked/half-frailed, Cale’s left hand danced on the strings like Chico Marx learning to type. His Kramer Ripley Stratocaster seemed oddly out of place in his hands. After all, this is the man who played one of the funkiest guitars on Earth. “It was an old Harmony round hole with five pickups in it. I used it on all my early records. When I started playing bigger gigs, I took the back off ‘cause it would feedback. I put one pickup in,” he said with a laugh. “And when that didn’t work, I put in another, and another and pretty soon I had five! I finally retired it.

“The Kramer is a strange guitar, but it fascinates me,” Cale continued. “Steve Ripley from Oklahoma designed it and Kramer put it out. It’s got a single pickup and I play it with the strings that came with it. It’s a stereo guitar, though I just play it in mono. Each string has its own pickup, so I can turn the G-string off if I want to. I just set it up for my touch. I’ve got a Marshall amp with four 12-inch speakers in it, but I don’t play it too damn loud! Sometimes, I use a Fender or a Cry Baby wah-wah, but the one I’m using lately is a no-name that sometimes squawks and squeals and makes a hideous noise. I think that’s why I like it,” Cale said with a laugh. “It makes the band mad. Every once in a while they start fallin’ asleep, so I turn that thing on and make it growl. I don’t use no rack of effects.”

Cale’s arsenal also included a nylon string Ovation acoustic, a Les Paul and a Fender Elite Stratocaster. “It’s one of the last American-made Fenders before Fender sorta went outta business,” Cale said. [Elite Stratocasters were built between 1983 and 1984, during a low point of Fender’s CBS-era ownership.]

Though he tried to deny it, Cale was something of a multi-instrumentalist, writing songs on the banjo, piano, guitar and sometimes the drums. He played dobro, too, although mostly at home and also played bass on a number of his albums.

Asked about how he felt recording his first album in his thirties, in an industry that is dominated by younger musicians, Cale shrugged and replied, “There was a famous banjo player in Nashville called Uncle Dave Macon. He was an astonishing songwriter and banjo player. He didn’t make his first album till he was nearly fifty. Wes Montgomery didn’t get any recognition until he was older. There’s hope! Don’t quit early, man! There’s nothin’ like bein’ young, but a lotta guys don’t even come into their own until they’re forty or fifty. So many guys give up because of economics. It’s hard to play music and pay your rent, too. If you can pull anything off, it’s almost luck.”

J.J. Cale died of a heart attack on July 26, 2013.

Author John Kruth is a singer-songwriter-multi-instrumentalist and educator based out of New York City. His latest book is Rhapsody in Black: The Life and Music of Roy Orbison (BackBeat Books/Hal Leonard). This previously-unpublished interview with J.J. Cale took place in October 1986. In light of Cale’s passing, we thought it was worth sharing. Cale was also the subject of a lengthy profile in the Fretboard Journal #16.