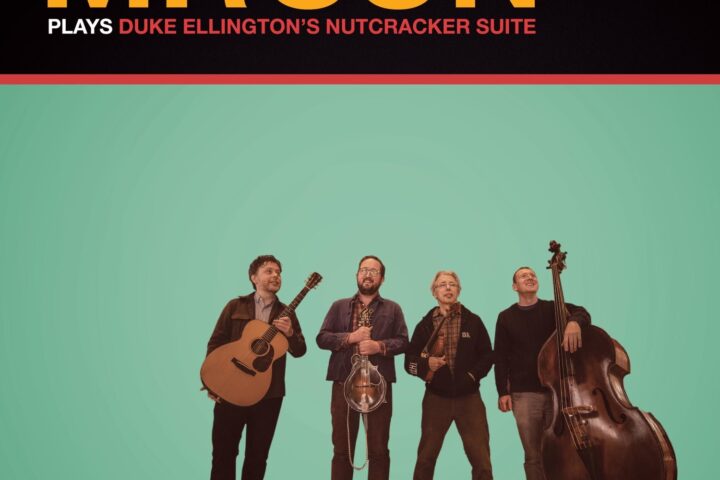

Guitarist Grant Gordy and mandolin virtuoso Joe K. Walsh first visited the Fretboard Journal five years ago. Ever since, we’ve been in awe of the varied acoustic projects (collectively and individually) this duo puts out, from their work in Mr.Sun and the Barnes, Gordy, Walsh Trio; to Walsh’s Borderland album; to Gordy’s collaborations with Ross Martin… and all points in-between. For their latest project, they roped in two more hotshot acoustic practitioners, bassist Greg Garrison and violinist Alex Hargreaves. Together, the quartet just released Bluegrass and the Abstract Truth, an utterly gorgeous album of instrumentals. Through the magic of Skype, we chatted with Gordy and Walsh about the unlikely making of this album (none of the band members are in the same town), the British bluegrass camp that brought them together and their new-ish instruments of choice.

Fretboard Journal: Where are you guys?

Joe Walsh: I just moved back to Portland, Maine, which is actually kind of blossoming with young musicians these days. A bunch of young mandolin ringers just moved here, so that’s great.

FJ: What is it about Portland, Maine? So many musicians are moving there.

JW: Just a little bit of momentum. It’s not a city, so, but it’s close enough that it feels like a good middle ground.

FJ: Grant, where are you?

GG: I’m in extremely south Portland… aka Brooklyn, New York! I’m in Windsor Terrace. We moved here right when the pandemic started, March 1 of 2020. It ended up being a very, very timely move.

Now that the weather’s starting to get nice again, it’s totally great. I’ve been trying to get on my bike and go around the park every day on this loop.

[Earlier today], I was coming around and some friends were playing at the park entrance. So I stopped and played “How Deep is The Ocean” with them before I rushed home. I’m still not really playing with people much. So it was nice.

FJ: Let’s talk about Bluegrass and the Abstract Truth. It’s incredibly beautiful. Tell me about how it came together.

JW: Well, there was just a sense of communal shared purpose. [The lineup] just happened to play about an hour-long concert in England a couple years ago. As I said to Grant, sometimes – if we’re lucky – it happens. And then we decided to try to take advantage of it.

FJ: What brought you together in England?

JW: There’s a camp called Sore Fingers, which is sort of the hub of the greater bluegrass community in England. We all happened to be on faculty there. They had this big stone hall that feels like it’s out of Hogwarts and they have various concerts every night. It was sort of really opportune.

GG: It’s a great scene. There’s a really good community of people in England of bluegrass enthusiasts and bluegrass / old-time enthusiasts. They’ve been doing this camp for years and years. They’ll have young upstart musicians from the States come over and teach. They’re just really good at fostering the community across the ocean. It’s a great scene.

We all have known each other for a long time. I’ve been working with Greg since I lived in Colorado, years and years ago. I’ve obviously known Joe for a really long time. Alex and I have known each other for a long time.

There’s been a lot of overlap over the years, but this group of four people never played together until in England. It was just a really nice chemistry. Greg might’ve started the text exchange … we should record!

FJ: So where are Greg and Alex normally based?

JW: Greg is in Denver and Alex is in Brooklyn.

I keep seeing Grant and I falling into bands really not based on convenience, at all. [laughs] There are always multiple time zones and thousands of miles making it harder to do a gig. But it’s nice to make music that doesn’t feel like it’s driven by filling a commercial need.

In a sense, it’s more of a pure reason to make a record than almost any other record.

GG: When we really got the momentum going with editing and mastering and starting to think about how we were going to release it, we were really in the deep throws of the pandemic. And there’s something about that that was a release in some ways. We’re doing this thing and it doesn’t feel like there’s all this pressure to get some undefined ball rolling, necessarily. If something develops in the future, that’s totally great, but it’s nice to just be able to focus on the record and just put that out. I feel pretty good about it.

FJ: When you first played together in England, was it just a jam session at a camp?

JW: I think it was a set. What was the name of the band, Grant?

GG: The Intergalactic Shrimpers! Every instructor at this camp gets their own set over the course of the week. You end up playing a ton. There’s all these people and there’s all this overlap, so everybody ends up working a lot during the instructor concerts. But everyone has their own featured set where they can do whatever or put a band together.

I think it was for Alex’s set. He led us as a quartet. And I remember he picked the name… “shrimp” has become sort of a shorthand for free improvisation. I don’t know why… and frankly I don’t want to know why!

FJ: Were there plans to get together in a real recording studio immediately after that live experience?

GG: Pretty much. We went to Dimension in Jamaica Plains, Boston. It’s like the go-to place for a lot of the Northeast acoustic stuff.

In fact, the first Mr. Sun record was done at Dimension, The People Need Light. That was done there.

JW: I think I’ve done like eight or nine records there.

FJ: And how did you decide on the material? You’ve got some covers. You’ve got some originals…

GG: It started as a big email pile… everybody tossed in ideas.

I had some tunes lying around that I had written, that weren’t really committed to any one context, and so I thought this could be a good opportunity to get those tunes recorded. And Joe is always writing a lot. At one point, Greg had floated a vocal song and then, for whatever reason, it ended up just naturally falling into all-instrumental category.

Strangely, there are two Grisman tunes, which we did not set out to do. It just ended up that way.

FJ: Before you recorded, was there much in the way of rehearsals?

JW: A day?

GG: I was thinking about that. I can’t even remember rehearsing.

JW: It wasn’t very much. Some of my favorite records that I’ve been involved in were made on a stressfully limiting amount of time. In this case, it wasn’t stressful, but it was very live. I think with the right combination of people, that works.

FJ: What instruments did you use on this album?

GG: I played my 1944 Martin 000-18. It was a month-and-a-half before I got my Suda [built by Japanese luthier Hiroshi Suda].

FJ: Is your new Suda a dreadnought or a 000?

GG: It’s actually kind of based on the Martin 000.

FJ: How does it compare?

GG: It’s totally different and it feels really comfortable, because it’s the same kind of guitar. The neck feels good; it’s a little bit easier to play. [On] the Martin, you have to wrangle a little bit more. But they’re just so different. The Suda’s brand new and the Martin is 75 or whatever.

FJ: Can you describe why folks like yourself and Critter are drawn to a luthier all the way over in Japan as opposed to all the other makers closer to home? What makes them special?

GG: Well, basically, I played one of Critter’s [Suda] dreadnoughts years ago, and it was really nice. I knew he was touring with it and it was a great guitar. I think he loaned it to me for a gig or something… I maybe had it for like a week or two.

I don’t know if we got in touch through email or something, but he said, “I’d really love for you to play one of my guitars.”

So he ended up giving me two different dreadnoughts. I had both of them for a year or two and realized that I was just kind of moving away from dreadnoughts. I was beginning to feel really sorry because I had these great guitars, but I just wasn’t really resonating with them.

He emailed me out of the blue a little while later and said, “I’m building you a 000!” I think it’s just a totally wonderful guitar. I’m perfectly happy playing it and will trumpet its virtues all over the world. It’s just a great instrument. So that’s my story.

[The vintage Martin] has been needing some work. I think it maybe needs a neck reset, and I’m kinda putting that off. In the meantime, I’ve had this brand new guitar to get used to.

FJ: Joe, what mandolin did you play on the record?

JW: Andrew Marlin had a Gilchrist that he liked that we both really liked and I kept encouraging him not to sell it. Then he got a hot idea to buy a Loar and then he called me up and sold it to me. That’s the mandolin I’ve been playing for the last two years now.

All us folks playing mandolins made in Australia… [laughs]

Far away. It’s strange.

GG: Something about that Pacific Rim…

JW: What an unpatriotic band we are!

Bluegrass and the Abstract Truth is available for digital purchase now and will soon be released as a vinyl LP.