In 2009, while dutifully manning my post at The Fretboard Journal, I got a call from my friend Tay Strathairn. He frantically barked at me over choppy reception, demanding that I leave work early, cancel whatever plans I’d made for the night, to go grab my gear and report to Nectar, a venue in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood, and sit in with his band, Dawes. Though I’d known Tay through other bands, I’d never heard a single note of Dawes’ music. Quick to dash any concerns I had about playing music I didn’t know, he assured me everything would fall into place during soundcheck. I followed my orders, and headed to Fremont.

When I arrived, the band was well into soundcheck, troubleshooting and working out whatever the kinks they’d discovered within the previous night’s show. I stood in the middle of the floor and Immediately, a thought came to me: “I should really put my gear back in my car and sit this one out. There’s nothing for me to add here, these guys sound perfect.” I was shocked. The band, well-oiled from the inconceivable amount of touring they’d consigned themselves to, needed nothing in the way of extra help, and certainly not from me.

There was the sibling lock between Taylor and Griffin Goldsmith, the guitar sounded great, keys too, but it was the depth of the rhythm section that was blowing my mind. I remember the first full song I heard during that sound check was “My Girl to Me,” a song arranged so as to give bassist Wylie Gelber the stage to act as the steady and unlikely star of the show. His tone was spot on and his pocket incredibly deep. I thought, “Holy shit! This guy’s the whole thing. There’s no band without him.” Since that night, I’ve had the good fortune to play and tour with the band extensively, and in doing so to really see the extent to which Wylie inhabits that role of quiet co-star, and occasional hero.

After that show in Seattle, (in spite of what I played while sitting in) I was invited to hop in their navy blue Econoline and cross the border into Vancouver for their show at The Media Club. At that time, I was playing a slightly non-traditional Telecaster Deluxe that I’d put together from Warmoth parts. During the drive north, it was Wylie, not Taylor, who was most compelled to get into the weeds about my guitar. Why’d I go with Warmoth? Why’d I choose the neck profile? How did I decide to go with a fretboard with compound radius? Though happy to talk shop as long as the next guy, I had the thought, “Dude, you play bass. How are you this pumped to talk about guitars?”

It didn’t take much longer for Wylie’s ancillary roles in the band to be revealed. They are, but are not limited to: Chief Gear Scientist, Guitar Tech, Pedalboard Designer, Electrician, MacGyver, and Head of R&D.

Since those early days, Wylie’s expanded his focus from solely keeping the Dawes battery of gear running smoothly to the newly minted Gelber & Sons, an outfit that produces truly unique and unexpected one-off guitars and basses, and also serves as a repository for all Wylie’s future endeavors. He and I recently got together in his new space to talk about his musical beginnings, wild pickguard materials, and selling guitars in the COVID-era.

Fretboard Journal: So, we’ve known each other for years, but I’m not sure we’ve ever talked about how you got started with music. I know that before Dawes, there was a band called Simon Dawes with Blake [Mills], but was that how it all started?

Wylie Gelber: Well, there was my band before Simon Dawes. I guess I’ve only ever been in two bands now that I think about it. [laughing] I had a band that seems like it went from third grade till I was 15. It had maybe six or seven names, but it always was the same group of guys. We gave it different names: LMNOP, Toothpaste, The City, whatever we thought was better we went for. It was Robert Commagere [Robert Francis] and my buddy Damon. It was like a full little kid garage rock band, which was cool, but every six months the style of that band would completely change. One minute it was “We’re Faith No More” and then, “now we’re an ’80s synth pop rock band.” It was just nonsense, but it was super fun.

And then when I was around 15, I met Taylor [Goldsmith] and Blake, and I thought, “Oh, these guys kind of seem like maybe they’ve got an actual trajectory going on here and not just slamming back-and-forth between genres.

FJ: How did you meet them?

WG: They were starting up what became Simon Dawes, and were looking for bass players. They’d tried out multiple members of my other band before they tried me out, which was hilarious because I was the bass player! They tried the guitar player, our keys player, but when it was finally my turn to try out, it seemed to work. All the other guys in my band were Blake or Taylor from the get go, you know? They could all play anything, and all of them were kind of prodigies in their own way, whereas I could only play bass, and I can’t sing and play bass at the same time, so with me I think they liked that they’d just be getting a guy who’s only interested in one thing. I also think they realized that if they filled the band with people who were all hyper capable that it’d probably get pretty psychotic, pretty fast. We do what we started out doing: Griffin (Goldsmith) and I keep things relatively simple, so that whatever’s happening on top can be whatever it needs to be.

FJ: When did you start thinking about gear? Were there any instruments that sent you on your way?

WG: When Simon Dawes made our record with Tony Berg, we started spending a lot of time at his home studio. He has unimaginable amounts of gear and there were obviously tons of things anyone could obsess about over there, but I’d already found my Gibson Ripper and never really got hit with the big to horde gear. I was 16 or 17, and my main thought about it at the time was basically, “I have this, it works, why would I ever need another bass?” It didn’t occur to me yet that having multiples of anything would be a good idea, as a player or even as a collector.

FJ: That’s obviously changed now. [laughs] When did that happen and what did it start with?

WG: For as long as I’ve been playing music and playing with these guys, I’ve been totally obsessed with tools and machinery. When we started touring a lot, things would break and, because I was out there with tools, I’d be the guy to fix things… even if I didn’t totally know what I was doing.

Once I got comfortable doing that, I started to look at our gear and realize that basically everything could be better. Whenever there was time, I’d start tinkering and working on things. I started with Taylor’s pedalboards, then my own rig, then Tay’s keyboard gear. It never really stopped. It was all just a big project I could learn from. It’s still that way, but we’ve mostly got our stuff dialed in now.

FJ: I know your dad’s been a big part of your journey with tools and getting comfortable with working on things. Can you tell me a little about him and his background?

WG: He’s a production designer for commercials and TV shows. In order to become a production designer, you generally have worked through every position in the art department. You’ve worn all the hats. So you’re a makeup artist, then you’re a prop master, then you become a person who knows everything… and that’s him. He knows how to do almost anything; there’s almost nothing that I’ve ever called him for wondering how to do or fix that he can’t just make sense out of it over the phone with me, and if can’t he immediately throws himself into researching the issue until he’s got it figured out.

FJ: Was he involved when you started building your first batch of instruments? I imagine if nothing else, it was a challenge for you guys to take on together.

WG: Yeah, all the first basses I made were all built with him in his garage. We just completely winged it. We’d pull out one of my Rippers, measure as many parts of it we could think of, and then we’d attempt to emulate it, but always with a slightly different take in mind. We did it with a very limited amount of tools: A router, a bandsaw, and a shit ton of sandpaper. Somehow we just made it work.

The first bass we made, our minds were kind of blown by how good it turned out. We were thinking: This doesn’t make any sense. Are we sure we made that? It’s got to be a fluke, let’s do it again!And it happened again. Oh, this one also sounds really cool. It actually sounds better than the last one!It was a really great way to start, because they definitely could’ve been terrible, but somehow they were great.

When I started getting my own chops and was more comfortable with the process, he wasn’t on the scene as often, but I’m on the phone with him three hours a day almost every day of my life. Either just walking through something I’m building or asking him how to do god-knows-what. He’s very much kind of like the CEO of Gelber & Sons.

FJ: How many guitars have you made so far?

WG: I think guitars there are 44 Radocasters out there now. Probably 36 or so of those went to people from Instagram or Dawes fans. The leftovers are either with Taylor or our lead guitar player, Trevor Menear. As far as basses go, I think the last bass I just made for myself was my ninth personal, which is a little nuts, but it is what it is. I’ve probably made five or six Radocaster-style basses. The only other person that has one of the basses that’s set up exactly the same way that I’ve got mine is Flea.

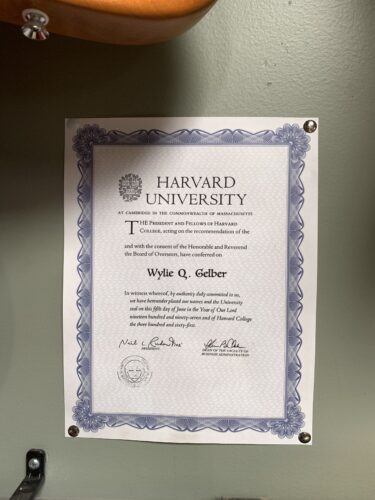

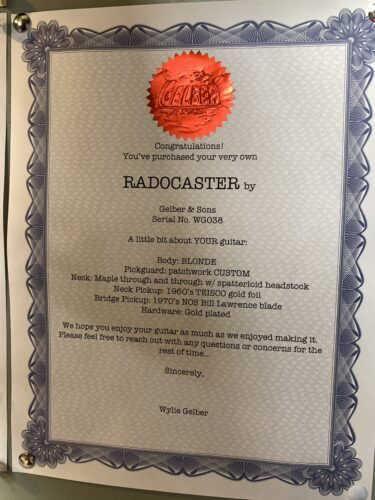

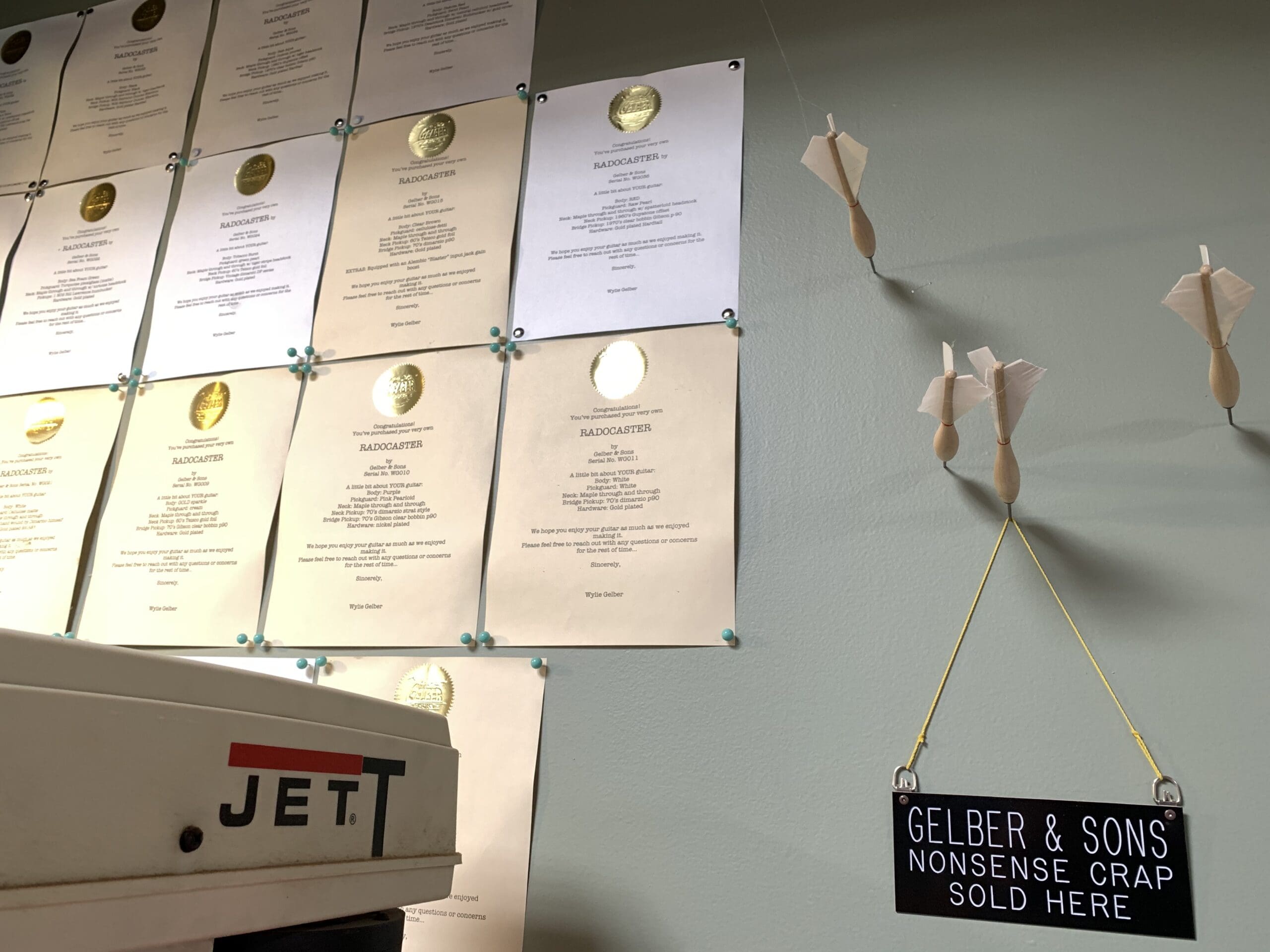

FJ: What can you tell me about these… diplomas? Obviously they’re certificates, I just never seen any like this.

WG: Yeah, I went for it with these. Customers get one that gets signed, and I keep one, and that’s what’s going on here with all of these [on the shop wall]. I was going for the birth certificate vibe, but they read more as a diploma. It’s cool now to see how they went through the different levels.

FJ: Looking at the shop, the obvious thing that comes to mind is that even though you’re a bass player, the bulk of the instruments you’re making are guitars. What’s up with that?

WG: It just happened this way. I’ve been playing with incredible guitar players for as long as I’ve been playing, guys like Blake, Taylor, and Trevor, and I’ve seen the kind of things that they’ve chased down over the years. I just decided to make sense out of all that in my own instruments.

One of the easiest things about making guitars is that there’s so much a crazy amount of obscure guitar gear that’s been made over the years, and it’s all just waiting on eBay. Old Bartolinis and DiMarzios that people have forgotten about and written off years ago… that’s where it’s at. I buy as much of it as I can when it pops up. [There are] so many dudes that have played thousands of bar gigs with these pickups, then swapped them out for whatever reason. Now, they’re just sitting in junk drawers, but they’re the coolest. Most everyone that plays one of my guitars are hearing pickups like these for the first time and everyone always freaks out about them. It’s cool.

FJ: And what about bodies? I can see that you’re using a bunch of different kinds. Is there an era you’re pulling from when you’re searching for them?

WG: I really like ‘90s Squiers a lot! I think they’re really good. I’ve got a soft spot for them because the first guitar I built, Taylor’s, was out of one. My brother’s high school guitar was a Squier, too. There’s something about them. At this point, a ’90s body has the advantage of having been aged. Like the pickups, I really like the element of people having written them off as sub-par, but they’re really not. They’re just out there waiting and they’ve got a real vibe.

FJ: How has business been since COVID hit? Have you been selling guitars?

WG: Yeah I have, which has been great. I generally tend to move as many guitars as I make. Since COVID, I think I’ve probably moved 25 guitars or so. It seems like people are seemingly dying to buy a guitar these days.

No doubt a lot of people are finally taking themselves up on the hypothetical, “If I ever had the time, I’d learn guitar”, and that’s awesome. I felt like a lot of the guitars I’ve sold recently are to new players and that’s really great to see.

FJ: One of my favorite aspects about the instruments you’re making is that, from the get-go, they all have a way of forcing people to reconsider their own taste. All of these combinations would never happen in the regular consumer market. Personally, I never thought about myself as being predisposed to buying a red guitar, but now when looking around the shop, all of a sudden I am.

WG: Yeah! That’s what I feel, too! I’m just trying to go for it with crazy combos. I really like that moment where people latch onto what I’m going for. So many people are out there, gravitating to a new Fender or whatever, that’s like, black with a white pickguard?! It’s like, Come on, man… just go for it! It’s a guitar, have some fun with it!

The guitars I’m making may not be what a lot of guys have been envisioning, but who cares? Literally everyone has those guitars, you know what I mean?

FJ: I do. And, because there’s no shortage of old Squier bodies out there waiting to be reborn, it seems like you and your customers will be set for a long time to come.

WG: For sure! That’s the name of the game! [laughs]

Sidebar: Stoned & Lonesome

“Stewart-MacDonald had a sale on their mini kits during quarantine. You and your dad could build a guitar. $120 or something. I got them and threw out all the parts that came with it… the hardware and the pickup and all this stuff. I cut custom pickguards for them and will put actual vintage pickups in them. They’re just octave up guitars.

“This is from my buddy Nick Gelormino, who’s this sick hand woodcarver. He’s super into the [mini guitars]. He borrowed that for a while, carved that, and the whole headstock is all scalloped, which is rad. I want to do an entire, full-sized guitar with him and just have him go full-on Grateful Dead… deeper than anyone’s ever gone… carve Jerry’s thumbprint into the back of it, etc.” -Wylie Gelber

Bottom portrait of Wylie Gelber courtesy Clara Balazary. All other photos: Ryan Richter.