Reno, Nevada, may be “The Biggest Little City in the World”—as an arching LED-lit sign across its main drag proclaims. The city is not, however, known as a hotbed of multiculturalism. One local musician is seeking to change that. Since moving to Reno just over two years ago, Chakrapani Singh has slowly been building awareness and appreciation there for the music and dance traditions from of home country, India. Singh founded TACH—the Traditional Association for Cultural Harmony—shortly after arriving in the Silver State, and he has been organizing events under the TACH umbrella since.

It would be a mistake, though, to consider Singh merely a cultural ambassador. He is, first and foremost, a compelling performer in the North Indian classical music (sometimes called Hindustani classical music) tradition. His instrument is a custom-made kacchapi veena. “In India,” says Singh, “the veena is known as the mother of stringed musical instruments, and there are different kinds of instruments whose common name is veena, including the vichitra veena and the gottuvadhyam. These are from ancient times. They are similar to my kacchapi veena, but not very portable.” If you look on Wikipedia, you’ll find even more veena variations. What they have in common is that they are plucked stringed instruments with a complement of sympathetic strings that enhance the sound of the primary strings. Veenas usually have hollow necks and include a gourd or two behind the neck to increase the instrument’s resonance. Singh plays his kacchapi veena with thumb- and finger-picks on his right hand and a bullet-shaped bar in his left hand. These are the same tools-of-the-trade that a lap-steel guitarist would use. Singh actually played lap steel for a short while early in his musical journey, 30 years ago.

According to Singh, the ancient veena is the great-great-grandfather of today’s guitar. “Many attribute the guitar as a Western instrument,” he says, “but the guitar-like veena was played in ancient days in India during the Vedic period [about 1750–500 BC]. The kacchapi veena was a well-known instrument of that period—used for solo performances and also as an accompanying instrument. It is believed to have migrated, later on, to different parts of the world and acquired different names while it vanished from India. The mystery of the origin of the guitar is probably is hidden in its name. The word geet is an Indian word for song. In Sanskrit, tar means string. Geet plus tar means an instrument with strings that can be played for any song.”

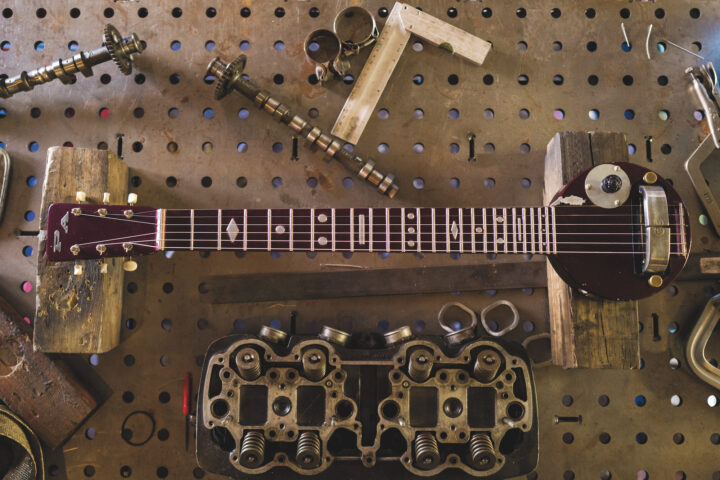

Although Singh’s instrument is not a guitar, many people who see it can’t help but call it by that name—especially those in Western countries. “The name kacchapi veena,” he says, “is just too big, so it’s easier for people to say guitar.” His instrument was built by Bhabasindhu Biswas, according to the Singh’s personal requirements. Other than its pine top and rosewood fingerboard, Singh’s veena is made entirely from one piece of tun wood, which is in the mahogany family. “I designed it,” Singh says, “to get the purity, perfection and clarity of the sound. There are primary strings and lots of sympathetic strings—35 strings in all—because in Indian classical music we use lots of microtones. The microtonal sounds connect with the sympathetic strings so the music comes out more melodious.” For his veena’s primary strings, says Singh, the tunings are usually based on C# major or C# minor. D# major and D# minor are used as well. “In Indian classical music,” he says, “each raga uses different notes. Sometimes the scale is major, sometimes minor, or it can even be mixed. Sometimes it’s five notes ascending and five descending, sometimes seven ascending with seven descending, sometimes six ascending and seven descending, and so on. You have to stick with those—you can not use any other notes. Whatever notes are used in the raga, the instrument’s tuning depends on that.”

Singh first became interested in music as a young boy in Darbhanga, in the Indian state of Bihar. He was inspired in part, he says, by his mother’s musicality. She wasn’t a professional, but loved to sing and gave him his first lessons in music. “I learned the vocal tradition of Indian classical music,” he says. “I got lots of things through my mother. But I didn’t like singing too much. I was most inspired by stringed instruments. I tried lots of other instruments first. Harmonium, sitar, tabla, and a little bit of piano too. Then I finally got the veena and started to play it. I find that you can do everything on this instrument—Indian classical music, Western classical music, and more.” Besides his familial inspiration, Singh says that he got to hear lots of great musicians when he was growing up, as Darbhanga was a popular destination for touring Indian musicians at that time.

When Singh performs, he is most always accompanied by two fellow musicians—on tabla and tanpura—as is the tradition in Indian classical music. The tabla is a pair of Indian drums, which you’ve probably seen or heard. (These are a staple of virtually all Indian classical music.) The tanpura is a stringed instrument that provides a constant drone note, over which the lead ensemble member improvises on a melodic instrument, such as the veena or the bansuri—a type of Indian flute. For some performances, Singh instead uses electronic instruments that simulate the musical functions of the tabla and the tanpura.

“There are two parts to the music,” Singh explains. “You have melody, and you have rhythm. This is nature—like man and woman. Melody without rhythm is not very impressive. If you play rhythm without melody, it can get monotonous. We need both, together. Then you will hear real music.”