There are precious few luthiers who can be trusted to rehabilitate a classic vintage guitar. It’s a grueling, time consuming task that requires endless repetition and equal parts imagination, elbow grease and art. When some of the best in that small circle are moved by the work of another, you can be sure that something pretty special has happened.

The Guitar

The centerpiece of this tale is a 12-fret Martin 000-28. Martin stamped the neck block on September 21, 1927. Most aficionados agree that the late ‘20s 000s Martin turned out were among the best guitars they ever built—and rival any vintage guitar for sound. The subject guitar was worked on by skilled (and some not so skilled) people in its lifetime. I first made its acquaintance at Norm’s Rare Guitar shop in the San Fernando Valley. A period correct Harptone case opened to reveal a generally good looking 000-28 sporting a huge, “moustache” bridge along with significant shadows from an old pickguard.

The Luthier

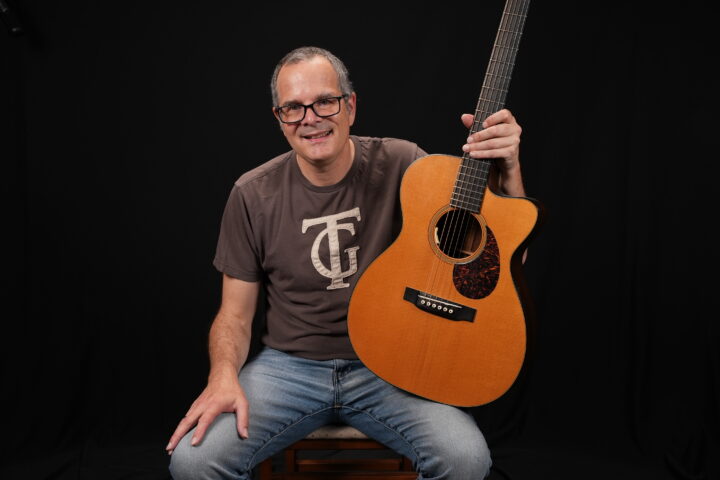

David Eichelbaum has been building and restoring guitars for close to 30 of his 50 years.

After initially building Telecaster clones and repairing all types of guitars including vintage acoustics, he began building acoustic guitars in the early 1990s. He gradually added his own unique interpretations of classic Martin and Gibson designs. For the last few years, he has focused on restoration of vintage instruments and a limited number of custom builds.

David is a slim, athletic fellow who is consistently mistaken for someone 10 years younger. His shop in Ojai, California is a small, meticulously organized work place reflecting its owner. On the sliding scale of great luthier workplaces, it is the polar opposite of Wayne Henderson’s free-for-all arrangement and more like (although smaller than) TJ Thompson’s beautiful new digs. One thing that differentiates David’s shop from any of them is the painstakingly, nearly re-assembled 1973 Kenworth K123 truck cab living in the garage which adjoins the guitar shop workspace. Guitars are David’s work and primary focus all week every week but old trucks are his weekend passion. He actually went through the crazy tough process of obtaining a commercial truck driver’s license so he can pilot this baby when finished. 1930s Martin and Gibson body parts often lie cheek to jowl on his work bench with truck door panels.

In the spirit of full disclosure, I presently own two Eichelbaum guitars. The first is a lovely, feather-light 00-18 built as an homage to a 1931 00-21 of mine that David worked on and fell in love with. I was so taken with his replica that I sold the 00-21 and persuaded him to part with the new 00-18. David also built me an “Eichelcaster,” a beautiful 1952/53-ish telecaster with pick ups he hand wound exactly to the Fender ’52 factory specs. A Eichelbaum OM is also due soon.

How He Did It

“It had seen better days,” David remembers. The guitar’s neck, back and sides were original but the top “had been poorly refinished after being sanded thinner than original. In particular, the treble side of the upper bout had been sanded quite thin to compensate for a loose upper transverse brace which had been re-glued with an ‘extra’ support piece but was now cracked again.”

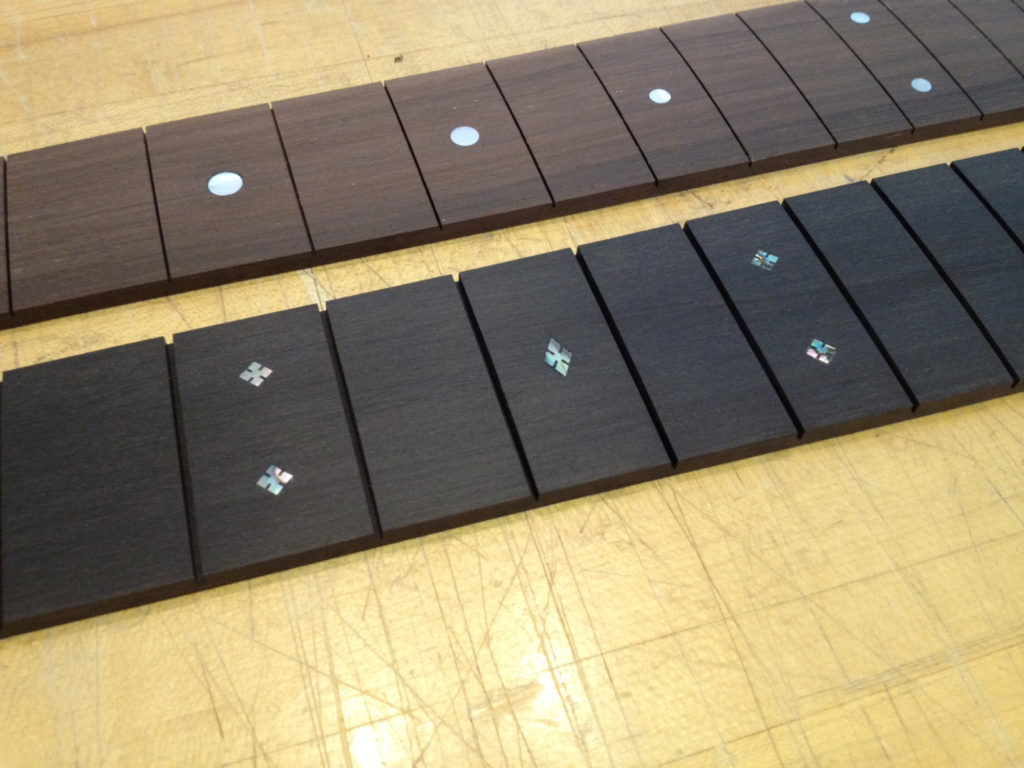

David noted the gonzo bridge and saw that the bridge plate was warped and split through the pin holes. It looked to have been subject to two or three aftermarket bridges each with the accompanying punches. The fingerboard wasn’t original and sported dot fret markers instead of the original style-28 “diamonds and squares.” Bridge pins, nut and saddle all appeared to be replacements, too.

Once a guitar’s top is sanded too thin, installing a new top can be the only recourse. But David thought otherwise here. “I never really considered replacing the top, it had been sanded, but mostly in the upper bout on the treble side,” he says. “The rest of it had maybe lost 10 or 15 thousandths off of its thickness but was holding up just fine. The guitar had been strung up for years in this condition and didn’t seem to be suffering. It sounded pretty damn good. The biggest structural issue in my mind was how to flatten that area in the upper bout and then put some arch back in it with a new upper transverse brace.”

Another common decision for vintage repairmen is how to deal with an original, but compromised bridge plate. Do you add a “helper,” use the Erlewine fill plugs or mix maple sawdust and glue to fill worn out pin holes a la John Arnold?

“In most cases I do all I can to save an original bridge plate,” Eichelbaum says, “but I recommended replacing this one. It was a judgment call based on the overall condition of this particular guitar. The original plate had very worn pinholes and several lengthwise splits so it was not doing much to support the top. Remember that the bridge plate is also a brace. Given that we were not dealing with a museum piece in terms of pure originality I decided that simply replacing the plate was the more sound solution and would provide better support for the thinned top. I made a new plate to original thickness and size out of hard rock maple. Making something oversized was not necessary and in the end the new plate is fairly transparent visually.”

On top, of course, was that crazy bridge. Would David make a new pyramid or belly bridge or even a new moustache? The current bridge had been heavily shaved and would need to be replaced. Ultimately, David opted for what would have been original to the guitar, a classic Martin-style pyramid bridge.

“The first order of business was pretty much the same as for any project,” David says. “Do an overall evaluation and then discuss with the client how far and how deep they want to get into it.

“I started by removing the neck and bridge and stripped the non-original top finish,” David says. “I used chemicals to remove as much of the shadow left by that bridge (and the shadow of the old guard) as possible and even out the color of the top in general. I refinished the soundboard using a combination of shellac [French polish] and a very thin nitrocellulose lacquer top coat to a dull sheen, not high gloss. I used a variety of chemicals to both lighten and darken the wood as needed. Almost no additional sanding was done.”

David then removed the cracked original upper transverse brace (and it’s “helper”) and constructed a new brace to restore some of the arch to the guitar’s top. “I then pulled the non-original fingerboard and fashioned period-correct replacement with diamonds & squares inlays,” he says. “Later, I installed the bar frets.”

During this process, David uncovered some earlier, less than stellar work. Underneath the fingerboard he found a mahogany shim that was installed to change the neck set angle without actually resetting the neck.

He then dealt with that pesky bridge and its bridge plate. “I removed the damaged bridge plate and replaced it with new one of appropriate thickness and ‘aged’ the color to match the overall patina of the bracing,” he explains. “I then fashioned a period-correct pyramid bridge with slightly compensated [slanted] saddle.”

After all this – and many odds and ends such as fashioning a new bone nut and saddle, replacing a missing section of purfling, crowing the frets, and adding Antique Acoustic bridge pins – he was ready to reset the neck at the proper angle “and tie everything back together.”

The Finished Guitar

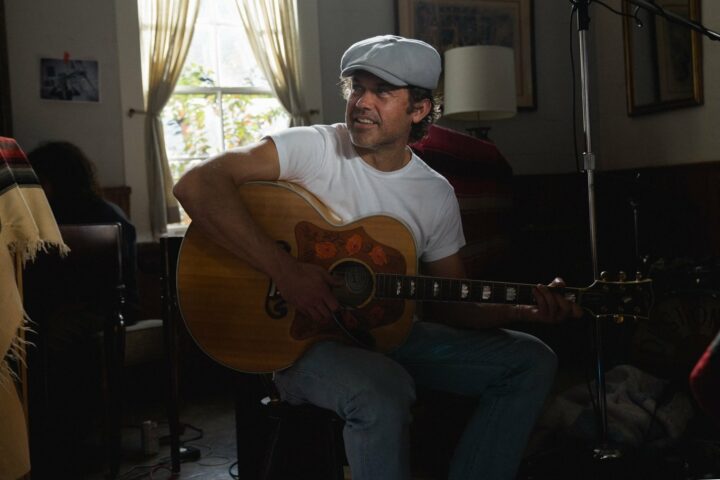

Needless to say, the guitar’s new owner, accomplished professional musician and studio owner Eric Garcia, is delighted. He recently took the finished 000 to Rugby, Virginia and pulled it out at the pre-Wayne Henderson Festival jam. Wayne examined the “before” photos alongside the guitar and called together all the “general loafers” (many of whom are fine builders themselves: Don Wilson, Herb Key and John Arnold). Shaking his head as he passed the guitar around, Wayne said over and over, “I couldn’t do that!”

“Much of the work I do is of a ‘restorative’ nature,” David says. “My two goals are always the same with every job: First, to return the guitar to as close to ‘as original’ physical condition as possible. Second, I want to ensure that the guitar plays and feels as it originally did. It all comes down to does the guitar look, feel and strike you the way it should? I feel like that’s something we achieved with 33098. It just happens to sound pretty darn good, too.”

As exciting as this transformation was to watch, what I’m really waiting for (along with several of David’s regular clients) is the day the Kenworth cab comes out of the garage. You see, as the restoration over the last couple years came close to completion, it became apparent that the vertical dimension of the cab was about half an inch higher than the measurement from the cement floor of the garage to the top of the garage door opening.

Talking among ourselves at a recent gathering, no one could see how he’s going to pull that off (actually, pull that out)—but the general feeling was, it looked impossible but David Eichelbaum would figure out a way to get it done.