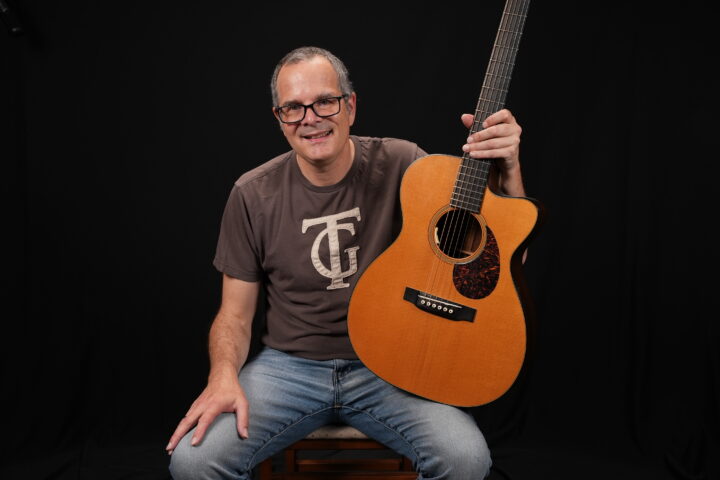

“Grand plans are often accidents,” Bob Taylor tells me over the phone. He’s not kidding. Though he helms one of the most successful guitar companies of all time, for nearly a decade, he’s largely been focused on one thing: Making sure that the world’s usage of West African ebony – one of the most prized woods in the guitar industry – becomes sustainable.

Why ebony? “This ebony mill became for sale,” Taylor explains. “It was first offered to [supplier] Madinter in Spain; it was really too big of a project for them. But since we were a client of theirs and they’re a supplier of ours, they asked if I would be interested in buying it with them.

“We went in there and found out how many laws and rules and Lacey Act things were broken in this business,” Taylor continues. “My partner called me on the eleventh hour and said, ‘There are so many things wrong with this business, I can’t go through with it. I’m not signing papers.’”

“I said, ‘I understand how you feel, I feel the same way but we can’t un-know what we already know… and we can’t un-see what we’ve already seen. If I don’t buy [this mill], I have to promise myself that I’ll never use ebony again. Because we’ll just be buying illegal ebony from somebody. So the only way to have ebony is to do it ourselves and make it legal.’”

Taylor and Madinter ended up buying that sawmill eight years ago. Since then, it’s been Bob Taylor’s main focus. “We’re completely dedicated to it but it takes all of our energy,” he admits. “We didn’t chose ebony, we fell into ebony.” Dubbed The Ebony Project, Taylor now has invested nearly a million dollars into researching the history, science and sustainability of these trees. And earlier this month, the collective had their biggest success yet. Thanks to their efforts, 1,500 ebony trees and 1,500 fruit trees were planted by members of five different communities in the Cameroon. It’s the largest single planting of West African ebony trees ever in the Congo Basin. And their plans for next year are even more ambitious.

A guitarmaker actually investing in trees? It’s a seldom-heard story so we decided to talk to Bob and Scott Paul, Taylor’s Director of Natural Resource Sustainability, all about it.

Fretboard Journal: You’ve been working on the Ebony Project for several years now. What happened this year that you were actually able to plant so many trees?

Bob Taylor: We finally had trees, which took us a long time to learn how to grow.

Scott Paul: Last year, we planted around 800 trees.

BT: We’re starting our fourth year in August. In that time, we learned how to make plants. The first two years were sort of non-fruiting years for the ebony tree, for the whole country. This last year, the whole country just sprang to life. We have 30,000 trees in the nursery right now for next year.

This year and the year before, we were hobbling along on the few plants we could make through vegetation propagation and also through seeds. We also have about a dozen plants now that we’ve successfully made through tissue culture in the laboratory. And they’re surviving. We’re probably a couple of years away at the soonest of really having that figured out. There will be five years of genetic, PhD-level work of figuring out the tissue culture secrets of this tree. But then we’ll really be able to make clean, disease-free trees from the elites that we find.

So this year it was a combination of getting enough mass in trees, and also having some fruit trees to plant. Also, about five villages have advanced to a point where they know what they’re doing and they’re eager to do it. They start out like, “You want us to plant a tree? You’re nuts!” But now they’re turned on.

Scott and I have a skip in our step. It’s been three years and I’ve spent $750,000 dollars to get us to this third year.

FJ: Obviously, you can’t buy an ebony tree at the local Home Depot. Describe the nursery environment for us.

SP: Our largest nursery is in Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon. We have a lot of plants that were produced from seed. Last year was a prolific seeding year and we were ready for it. We have about 30,000 plants at that nursery. Some of the plants were big enough and hardy enough that the decision was made to transplant them to the villages. The majority will fatten up for a year [before getting transplanted].

Meanwhile, in three of the village, starting a year ago, we started teaching them how to build what is called a non-mist propagator – it’s a simple technology made out of wood and thick plastic. You fill it up with rock or river sand and you produce plants from a cutting, just like my mom does in her garden.

A percentage of the plants are being produced in the villages through cutting. I’m going to say 600-800 of the plants were produced at the village through cutting and the remainder were produced from seed grown in the capital and then transported out to the villages where they were slowly carried out into different settings.

BT: One of the most exciting things is that the trees we planted last year and the year before are thriving.

SP: That was the most rewarding part of this. We knew this was going to be our biggest planting. We learned a lot from our first planting. We decided we wanted the trees to grow a bit fatter and bigger in the nursery before we put them out in the wild. But I have to say that it was incredibly heartening to see the survival rate of the plants from two years ago and last year. The survival rate is above expectations. We’re talking 70-80% survival rate. And the plants we’re putting in now are only bigger and hardier than the ones we planted one or two years ago.

FJ: How long until an ebony tree is mature enough that you don’t have to worry about it getting hurt, trampled or dying?

BT: I think that probably 15 years is the time where you think that nothing will trample it. The nice thing is that people have planted these trees with effort. They’re not going to trample them and they’ll keep an eye on them because they have some sweat equity into it.

But the truth is that none of us know how old an ebony tree is that we’re cutting. My thinking is 100 years minimum. And it may be 200.

FJ: How can you not know the age? No one has been able to carbon date a tree?

BT: No one has. Maybe you can. But you can’t count ring lines on a tropical tree like you can on a temperate tree.

SP: There’s also a period of time where we don’t know when the tree has become the perfect tree for wood. It may live for another 75 years and start to rot from the inside. What triggers that? We could have a tree that’s 200 years old, but maybe the perfect time [to cut that tree] was 80 years or 120 years… nobody knows!

BT: When trees get old, before they die, we call that “standing mulch.” They look like this huge, giant mega tree but they’ve passed their age of viability. They’re at their end of life and it’s just a big rotten hollow tube in there.

FJ: It’s great to hear that the local villages are behind this. You earlier mentioned that they also planted fruit trees? Is that why they’re so excited about this project?

SP: One of the things that is special about this project and has captured a lot of attention from folks at the World Bank and elsewhere is that marriage of planting a tropical hardwood that could take generations to be of economic value and fruit trees, which would literally be bearing fruit in three to five years. There’s definitely a great appreciation for the fruit trees that are going in.

BT: It’s more than we hoped for. Let’s just reel back in for a minute and pretend that we didn’t get this wonderful, emotional connection that these people have. It’s an emotional connection that is taking them out a century out into the future and getting them thinking about their great grandchildren.

The initial proposal was simple: We want to bring you fruit and medicine trees you can use, maybe a cash crop that you can sell. You can grow food that you like to eat and then you can plant some high-value hardwood trees. We’re actually paying them a fee every year for the first five years to keep those ebony trees alive. Imagine there’s a farmer out there who hasn’t started any of this. He’s loathe to plant an ebony tree on day one because it’s just a bunch of work and he’s going to have to take care of it. It’s going to be his great grandchildren who get the benefit of it. But if we give them fruit trees, he’ll say, “Yeah, but it’ll be five years before I get fruit.” If we give them grafted fruit trees, that will give you fruit in two or three years…

But then they get some money. They don’t need much. It gives them income. Then, when that five year payment falls off, they’re harvesting fruit. And maybe even a cash crop. And the world is eating more chocolate every day. That’s the [crop] that people tend to go to. That’s the program. But we’re getting more than that, an actual emotional buy-in. And that buy-in didn’t come on year one.

SP: It’s just beginning to crest. We’ve been doing it, we’ve been believing it and arguing for it, but we’re starting to see that it’s going to work.

FJ: What caused the breakthrough seeding year? The climate?

SP: We don’t really know. The project that Bob is paying for supports a PhD who is considered the leading expert on this species of ebony. His theory is that every three years or so, it’s just a cycle. There’s an off-year and the trees are exerting energy towards other purposes – roots or leaves – but every third year the female trees are ready to go and produce a prolific amount of fruit. It kind of surprised us. Vincent Deblauwe is the biologist, that’s his working theory.

BT: Vincent will be publishing scientific papers soon. We’ve got to get him out of Africa for a few months to really write them. We need those papers. Nobody ever knew anything about this tree and we’re writing the bibliography on it now. For example, we now have the exports of ebony from Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, all the way back to 1890. What’s amazing is that it turns out they weren’t taking more ebony back then than they are now. It’s almost equal to what we take. But, at the turn of the century, Cameroon made a law that if anyone brought ebony to the port that wasn’t pure black they would not only get that wood rejected but they would also receive a fine for it!

I’m driven to convince people that you can’t use only the black ebony trees, especially now. And guitar builders around the world are the problem, not the consumers. The consumers are ready for a fingerboard that isn’t black, they just don’t know they have a choice. It’s the guitar builder who is so afraid that he might have to answer that question or lose a sale or take an hour longer for a sale… it’s the guitar builder that is stuck in the mud. We’re finding that more and more people are sticking their feet in, planting them deeper, and saying, “I like what you’re doing but I need black wood.” And they’re able to get black wood is simply because there’s black wood on the market.

I’ve spent the last eight years of my life doing this one project. Taylor guitars runs by itself. This is almost all I do. When suppliers are delivering a high percentage of black wood, it’s because they’re getting it in illegal places and via illegal methods. I know how our permits work. Black wood comes from the center of the country; in the rest of the country, it’s very sporadic. Out of our 1,400 tons we’re able to cut this year, only 150 of it can even come from the area where the black wood grows. And not every tree in that area is black.

So there are some people who gather their wood by taking a 20-ton truck and drive around Cameroon. Villagers cut down a tree and they pick out the black wood and pay cash. Those trees aren’t geo-tagged, they’re not from a legal place, they’re not following permits… it makes me cranky. We are doing all of those [legal] things.

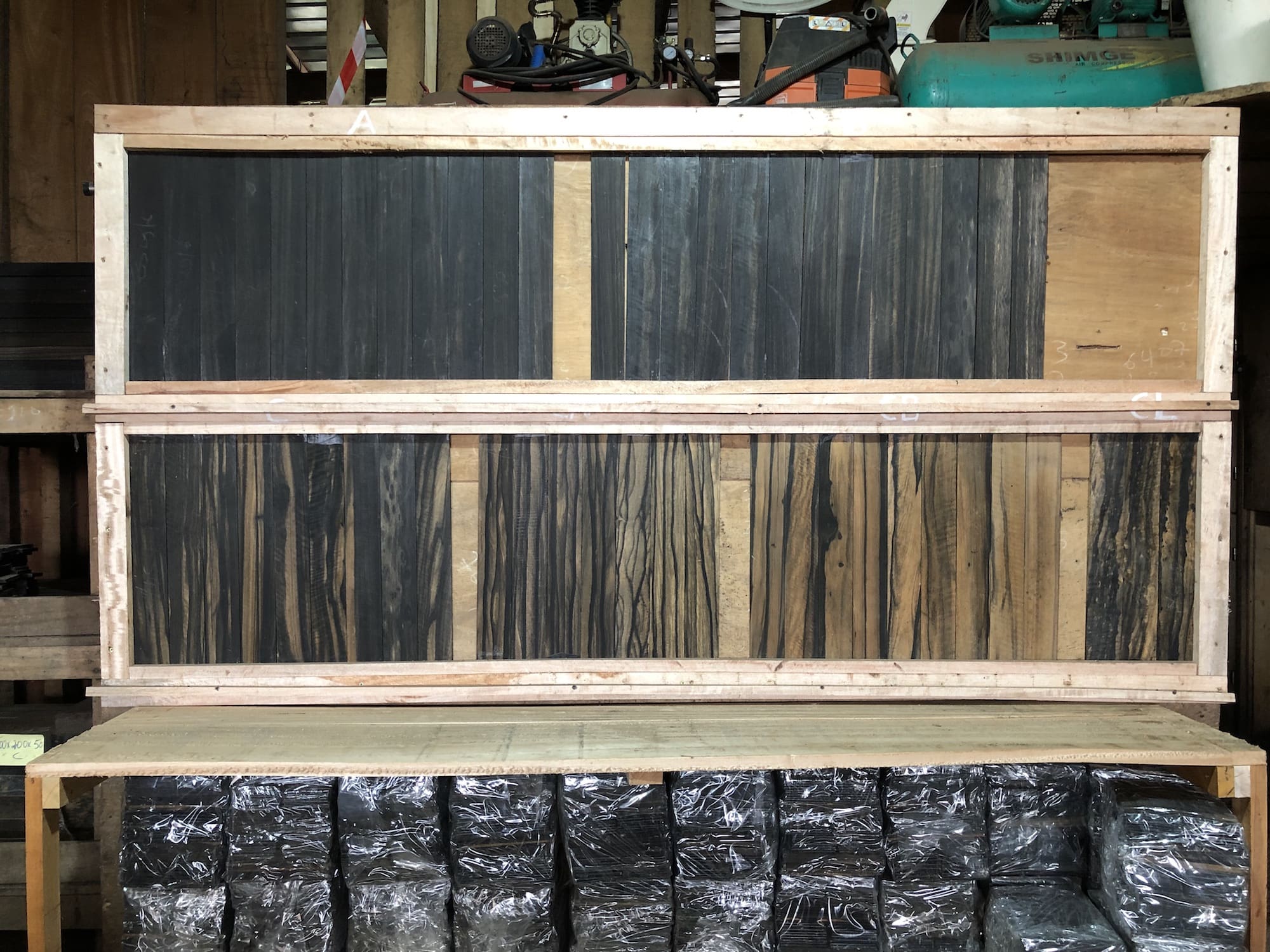

I’ll show you a picture that I call the ebony Pantone scale. All the colors that ebony comes in. [Colors] A, B, C, C Natural, Rose Ebony and the last two, we call Leopard. Ten percent of the trees yield A.

My hat goes off to Fender guitars right now. They’re using the super highly-colored ebony from our mill on their Acoustasonic. You look at those guitars and it’s just every color under the rainbow. They make them proudly. And their customers snap them up. That guitar was the highest selling acoustic guitar model for the last month!

It’s amazing to think that back in 1910, customs decided to write citations for wood that wasn’t jet black. And you wonder how we got to where we are today!