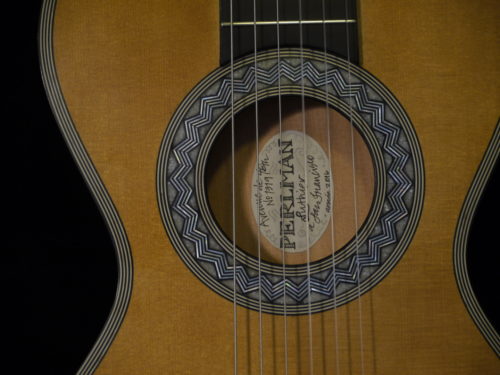

Not long ago, our friend Jim Brown of Jet City Guitars brought to our attention a fantastic Roy Smeck conversion performed by the Bay Area builder Alan Perlman of Perlman Guitars. Alan’s managed to set himself up with an impressively balanced portfolio of work doing repairs and full-on restorations as well as building his own steel-string and classical guitars, including some stunning recreations of historical instruments, not to mention the occasional harp guitar.

Fretboard Journal: What’s on your bench right now?

Alan Perlman: Right now, there is an 1865 Antonio Torres–what appears to be a very interesting experiment by the old master–a full but not extreme restoration. There is also a 1931 Martin OM-45 undergoing extensive repair for old water damage and a 1936 Gibson Roy Smeck; it’s had a difficult life, major bad modifications. I’m trying to return it to its original condition, as much as one can.

FJ: How did you get started?

AP: I’ve always enjoyed building and repairing things, from a very young age. I’ve played guitar since the age of 12. I moved to Vermont in my late teens and was surrounded by woodworkers and a few instrument builders; I was also a close drive to Michael Gurian’s Hinsdale, New Hampshire shop. He had a full line of luthier supplies, wood and tools. And extremely helpful advice. I had a much older friend, Clark Voorhees, who was an incredible woodcarver and dulcimer builder. Much inspiration and knowledge came from him. The story of my time in Vermont and the people I worked with could fill a book, a rich and, formative time.

Irving Sloane’s books, beginning with Classic Guitar Construction were incredibly helpful. I was a sponge for any information I could run across and seemed to have an innate understanding of how things work, be it guitar acoustics or rebuilding the sawmill and diesel engine, always willing to learn and, as I became older, realizing how much I didn’t know and how a life of immersion in luthiery would slowly bring me to a place where I could accomplish what I had hoped for in my work.

FJ: Can you tell us about your shop?

AP: My shop is in a small room in our home in the Outer Sunset in San Francisco. Large power tools and storage are in the lower level. I’ve been in this location since 1997, in San Francisco since 1983, and Vermont for 12 years before that. Proximity to Golden Gate Park and the ocean makes it a lovely place to work, and also gives me the dubious opportunity to keep dehumidifier companies in business.

A rare peak at an interior side view of an 1867 Antonio Torres guitar (FE24) on Alan’s bench for extensive repairs.

FJ: Do you have a particular philosophy about wood/materials?

AP: I’ll use recycled/salvaged materials when I can; they can be of wonderful quality, and also have the benefits of age and of course are environmentally preferable. Rosewood beams from the 1940s, all sorts of stuff. Otherwise, I look for the highest quality materials I can find. Spruce soundboards come directly from the cutters in the Alpine regions of Switzerland and Italy. Excellent Adirondack spruce is available, very expensive but worth it since it is graded from both a cosmetic and acoustic viewpoint.

There are excellent alternatives to Brazilian rosewood, though this remains perhaps my favorite back and side material. I purchased some Ceylon satinwood that was cut in 1981; this has proven to be a wonderful back and side wood. Swiss pearwood and birdseye maple have proven to be excellent choices for the 19th century-style instruments I frequently build.

I most frequently purchased wood from non-luthier sources–often better selections and quality if you’re willing to spend time and dig deep.

FJ: What’s the balance of steel string vs. classical builds in your work? Are there any particular challenges that come up, working in the two styles?

AP: It depends. For building commissioned instruments, it’s roughly 50-50. Repairs run more heavily towards steel strings on an everyday basis, but a large historical classical restoration could tip the scale heavily. The challenges, in a way, are similar; extreme care, appropriate materials and glues and good communications with the owner. Some of the older, high-value guitars may require more of a museum conservation approach. A guitar like a Torres poses additional challenges due to its extremely light construction, super-thin sides and top and awful repair history. I am a big fan of hot hide glue; it’s a superior adhesive, does not creep and is reversible.

The greatest challenges are frequently posed by whoever has worked on the instrument previously. Poor techniques, damage, wrong glues and incorrect replacement parts are common.

FJ: Are there any upcoming projects that you’re particularly excited about?

AP: I’m about to build a guitar for a wonderful guitarist, Jon Mendle. It will be very similar to an early 1800s Lacôte “heptachorde,” a seven string guitar. It will be built of spruce from Switzerland and figured Swiss pearwood. Tuning machines in the style of the original are being made by Rob Rodgers.

Also, the Torres mentioned above. The guitar is currently not playable. Torres omitted the cross brace between the sound hole and bridge, using the tornavoz and four posts between the tornavoz and back to support the soundboard. As far as I know, this is his unique approach and I’m excited to hear how this guitar will sound.

Really though, I’m pretty excited about most projects I work on. A neck reset on an old Martin or Gibson, seeing the improvement in sound and playability always jazzes me, as does any difficult repair completed. And of course there are the nightmares…

FJ: Nightmares? Anything you need to get off your chest?

AP: A few stories…

Torres FE 24. I was ready to remove the back of this guitar, a task necessitated by the large scope of work needed in the interior and the presence of the tornavoz blocking all access to the inside. After removing the binding, much of which was missing/sanded through already, I began to use carefully applied heat and moisture, using thin spatulas to loosen the glue line. This should have taken two to four hours, roughly. Nothing. Wouldn’t budge. The back was glued on with a white glue, the sort that was used in Spain and Latin America, at times. It takes a lot of heat to cut through this. I fashioned a thin tapered chisel that fit on the end of a rheostat controlled soldering iron. I used this to slice through the glue line, really slow going–it took several days, and I think my right arm fell off in the process. I can’t remember, luckily.

Another was a 1936 Martin 00-18. This was a neck reset for a touring musician. I could keep the guitar for just under two days, just enough time to reset and refret. I began injecting steam into the dovetail and after a reasonable time realized that nothing was happening, the neck was not loosening. Through a tiny hole in the fret slot, I drew out a small piece of glue on the end of a drill bit. I dropped the glue bit into boiling water, watched it dance around for a while and found that it had not softened at all. It was epoxy! Using a very thin Japanese saw and an ultrathin stainless steel sheet protecting the guitar side, I cut the neck (not the fretboard) off, flush with the body; because the saw was so thin, barely .010 inch was lost. I then fabricated and installed a new dovetail in the neck and from that point on, it was a conventional neck reset. I was able to return it just in time, no visible indication that there was a problem and the next person will be able to remove the neck by conventional means.

I have sort of a philosophy about repairs. I know I’ll get in trouble for this: They’re like bad relationships. You meet someone. Seems good, take them home. You’re sure (bad idea) you can fix them up . But then you find out that somebody’s been there first and made a total mess of things.

FJ: Do you draw a line between “repair” work and “restoration” work?

AP: I don’t know that it’s a line so much as a continuum. It can be a question of scope; re-gluing a bridge is a repair while reconstructing a severely damaged instrument can be seen as a restoration. Historical instruments pose additional issues. If a two-year old Martin needs to have a side replaced, I’ll find a matching piece of wood and replace the side. On older valuable instruments, I’ll go to great lengths to preserve what is there, adding new wood (actually old wood) only if absolutely necessary.

Again, the conversation with the owner is extremely important. Are we just trying to arrest deterioration or will this guitar be restored to a fully playable instrument with finish work that will bring out the beauty of the wood and inlays? I will usually go with a knowledgeable owner/collector’s wishes, guiding them to a more gentle, less invasive approach if that is appropriate. Any decision made will invariably incur the wrath of some. I like to imagine that the builder of these guitars would like them to be placed in caring, skilled hands, reversing the ravages of time, abuse and poor repair work. I certainly feel that way about my instruments.

FJ: You recently built a replica of an 1830 Lacôte; how’d that come about, and what can you tell us about the guitar?

AP: The original belongs to the Harris Guitar Foundation, the collection of John Harris. I’ve had the opportunity to work on that guitar (I’ve worked on a number of John’s guitars, I’m eternally grateful to him for this) and when it was in my shop I took extensive photos, dimensions and tracings of it. I also used a boroscope–a tiny camera surrounded by LED lights mounted on a long flexible shaft–to photograph the inaccessible interior of the guitar. John would meet with the students at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music weekly and give them the opportunity to play and talk about instruments in the collection. Kyle Sampson, a guitarist who until recently lived in San Francisco, fell in love with this guitar and commissioned an exact replica.

The Lacôte has a number of unique features. One is a complex rosette, built of mother-of-pearl, ebony and holly. There is a second soundboard, about 30mm below the top. It is a 2 mm-thick piece of spruce, unbraced, does not touch the sides and is supported only at the neck block and tail block. The back has an oval shaped sound hole near the center, lined with a thin piece of ebony. The only departure from the original was replacing the ebony friction pegs with Wittner planetary geared flamenco pegs. These look like ebony pegs but function like a fine guitar tuning machine.

This all resulted in a guitar that had far more volume than its small size would suggest and a beautifully complex voice. The second top seems to add a great deal to the tone and volume; I intend to experiment with this on other instruments, both steel string and classical.

FJ: Do you have a favorite guitar that’s crossed your bench?

AP: Tough question. I’ll pick a few.

One of my all-time favorites is the Stahl #6, built in the 1920s by the Larson brothers. This was the higher end Brazilian rosewood and spruce X-braced model. These were unique in their doming of the soundboard, bracing layout and profile, and body dimensions. I think they’re near the very top for fingerstyle instruments. I’ve built six replicas and love the results. Stevie Coyle owns one and speaks about it and plays it on the Peghead Nation website.

There was an 1867 Antonio Torres (FE24), from the collection Sheldon Urlik. It was a beautifully made, elegant guitar, exquisite rosette and purfling, incredible European birdseye maple and a voice that was just magical. It was a severely compromised guitar, requiring extensive restoration.

Perhaps most significant of all was the Antonio Torres guitar, SE49, that was built for Francisco Tarrega, the famous composer and guitarist of that era. After I did the initial restoration work, several guitarists said it was the best guitar they’d ever played. I will be doing a more in-depth restoration at some point and there has been some talk about writing an article about this instrument, its history, its construction, and its lineage.

Another that comes to mind was an unusual parlor guitar that I restored for my wife, Sue. Its label said “The Edwin American.” It had a four-digit stamped serial number. Fine Brazilian rosewood and spruce, beautiful inlays and a double X-braced top, unusually laid out and very lightly braced. And a killer tone!