Luthiers are often solitary figures, working long hours alone in their shops, slowly building beautiful instruments, doing a few repairs and making a lot of dust and a little bit of money. If you’re lucky, you might play music well enough to have a career or at least get a few gigs now and then, so you don’t feel like you’re a total hermit. Maybe you can find work teaching or giving private lessons to people. Then you’re almost making a living!

Luthiers don’t often leave a lot behind — a few instruments, some tools, some old wood, some unfinished repairs and a pile of weird-shaped kindling. Not much on paper either — some drawings, maybe a list of serial numbers, old receipt books, some sort of a ledger, a scrapbook and maybe a few photographs.

We know many of their names quite well: Martin, Gibson, Stathopoulo, Loar, Dopyera, Weissenborn, Maccaferri, D’Angelico, Fender. These are men whose instruments made an impact on the world. They’re famous, but they’re not exactly celebrities. And then there are the hundreds of lesser-known makers — self-taught regional builders, immigrant luthiers, factory workers, part-timers, hobbyists and local hacks. Each had their own ideas, their own twist. Each were trying to literally make their mark.

Here is the story of two such guys, John Henry Parker and Joel Louis Eckhaus, two New England builders who worked alone, who built mandolins, banjos and guitars, who played music professionally, who taught music, and who even lived in a couple of the same towns…a hundred years apart.

In 2007, I stumbled upon an instrument on eBay with the words “THE BANDOLA” on the headstock. It had a strange shape, kind of like a garlic bulb with strings. It did (sort of) resemble a Venezuelan bandola, but with four double-wire courses, it was clearly a mandolin. As I recall, I was the only bidder. I can’t even remember the price, but it was not a lot. It just needed a little glue, a piece of binding, a tailpiece and a set of strings. It sounds very sweet, and it plays very easy. It turns out the instrument was made right here in Portland, Maine. It says right on the label “THE BANDOLA, Mandolins, Banjos, and Guitars, Patented, The Bandola Co. Portland Maine, Sole Manufacturers, No. 1462.”

If you Google a name like The Bandola Co., you don’t get a lot of hits. But the one that comes up first is from mugwumps.com, where Mike Holmes created a list of North American fretted instrument builders from pre-Civil War era to WWII. There I found a listing for the Bandola Co. in Burlington, Vermont, 1899–1905.

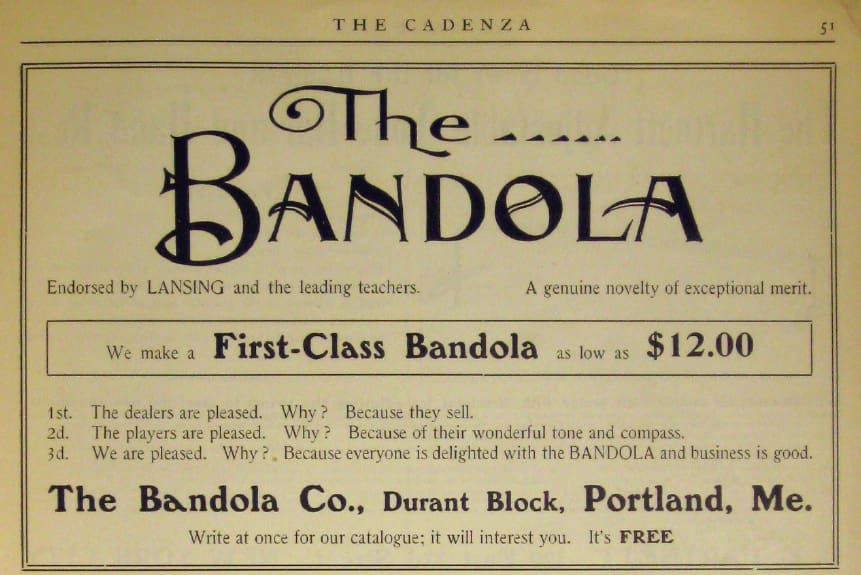

Another hit was Gregg Miner’s Music Museum at minermusic.com. Gregg is no stranger to this magazine and has a comprehensive collection of harp guitars, some of the most strangely beautiful stringed instruments in the world, and a few other things, including another “The Bandola” mandolin. He’s also found some Bandola Company ads in the Cadenza magazine, ca. 1907. One shows a picture of a mandolin similar to mine, with the copy, “SOMETHING NEW But Far Better Than The Old, PATENTED, SEE THAT SHAPE, This First Class Bandola Mandolin for $12.00.” The other ad has a picture of an octave mandolin with a fifth string (or in this case, a ninth string!).

“Another New One” the ad says, “PATENTED, The Bandola Banjo (Double Strung) SEE THAT SHAPE. Our Motto ‘ORIGINALITY.’” It goes on to describe the wonderful tone, and the fact that you can “play it as a Banjo or an Octave Mandolin (without changing the strings), 2 in ONE.” Both ads list an address on the Durant Block in Portland, Maine.

Miner also had a copy of a U.S. Patent awarded to John H. Parker, of Montreal, Canada, on August 7, 1894. The patent shows drawings of a guitar and a mandolin similar to mine with a “cut away portion…rendering possible the use of a more extended scale and Improving the tone” as well as for an “improved construction of tailpiece whereby the rough portions of the strings are effectively covered up” (in other words, an early version of the scallop tailpiece).

I searched online for John H. Parker, instrument maker, and found him listed (at Mugwumps again) in Montreal, in 1894. I also noted a listing for a “Calvert” Parker, in Keene, New Hampshire, circa 1922.

I was teaching woodworking at Maine College of Art, in the old Porteous Department Store building, when at lunch one day, I went over to the Maine Historical Society Library just down the street. It’s a beautiful library full of musty, dusty old books. (It’s worth it to go in there, just for the smell). Here I found, in the 1908 and ’09 Portland city directories, “Bandola Company, 536a Congress Street John H. Calvert-Parker, music teacher.” I also found a residence for John H. Parker at 126 Sawyer Street in South Portland.

I was soon out the door in search of 536a Congress, which in fact was right up the street, next door to my employer. The old brick building is labeled “Durant Block” in neatly carved granite letters. It currently houses a hip young art gallery, with artist studios on the upper floors. It’s all part of Portland’s new creative economy.

On the way home, I stopped by 126 Sawyer Street (in what we call nowadays SoPo). Right across Sawyer Street from Evelyn’s Tavern (a creaky old dive bar in Ferry Village) is lot No.126. It’s a flat-roofed double-decker covered in gray vinyl siding, with a defunct-looking gift shop on the ground floor. It looks like it could be a hundred years old, but maybe not. It’s less than a mile from my house on Meeting House Hill. John Henry Parker lived and worked right near where I live and work — a hundred years ago!

Next, I called up my old friend Robert Resnik, an eccentric Jewish/bookish musician-type with the perfect day job: research librarian at the Fletcher Free Library in Burlington, Vermont. He did a quick search for John H. Parker in the Burlington directory and found two listings for him at 51 N. Willard Street and 230 College Street — the library is on College Street. I asked Robert if he was anywhere near 230. He looked out of his office window and said he could see the building!

I’m not a particularly religious guy (thanks largely to six years of Hebrew school), and I

guess my spiritual side is kind of undeveloped. But at this point, I felt like maybe I had some sort of a connection to Mr. Parker.

John Henry Parker was born in England, Ireland, or Wales (depending on whom you ask) in November of 1860, the son of John Calvert Parker and Elizabeth Emerson. He emigrated to Quebec in his early twenties. He’s listed in the 1893 Montreal city directory as “John H. Parker, EXPERT TEACHER, and Manufacturer of the ‘PERFECTION’ BANJOS, Bandolas, Guitars, and Mandolins, 131 Bleury.” He married Elizabeth Sara Armstrong in 1885 and they had two girls, Mildred and Grace Parker.

Parker received a patent in 1894 for his uniquely shaped mandolins and guitars. The design improved access to the upper frets of the instruments by cutting away the upper bouts on both sides of the neck. While reducing the size of the bodies, he claimed to improve the tone of the higher registers, and he provided a full two-octave fretboard. He also patented a one-piece metal tailpiece that anchored and covered the sharp ends and windings of the loop-end strings.

The family moved to Willard Street in Burlington, Vermont, around 1900. They had a couple more kids, Paul and Ruthven, and John Henry set up a workshop and music school on College Street. A photo of Mildred was featured in the Cadenza magazine in September 1901, age 8, in a little white dress, holding a Bandola mandolin. She is described as something of a prodigy, able to read up to five sharps or flats, with a program that includes works by Chopin, Mendelssohn, Schumann and Beethoven.

The Parker family moved again to Portland, Maine, and had another son, Philip, in 1907 (who died in the great Spanish flu epidemic of 1918). They lived on Sawyer Street in South Portland, where John Henry set up The Bandola Co. on Congress Street downtown.

He is listed in the Portland directory as a music teacher. One of his students, Dorothy Van Tassell Barnes (a divorcée), seemed to take a special shine to the banjo, the guitar — and to John Henry. One relative reported that Dorothy’s lessons sometimes lasted several hours.

For reasons that we can only speculate, John Henry and Elizabeth Parker separated sometime after 1910. Elizabeth moved to Somerville, Massachusetts, with Paul and Ruthven, and is listed in the 1920 census as a widow and a dressmaker. Paul went to MIT, moved to Sacramento and worked as an engineer. Ruthven stayed up in Somerville and married Richard Joseph Walsh in 1931.

John Henry moved to Keene, New Hampshire, with Dorothy, her two daughters, Hazel and Marion, and two of his daughters, Mildred and Grace. He set up The Bandola Co. in the old Ralston House Tavern at 59 Davis Street and produced a line of mandolins, guitars and banjos. He sold them to dealers and his students at The Parker Banjo, Mandolin and Guitar School. One newspaper clipping states that he worked solo in a 600 square foot shop and made over 500 instruments a year, which, if true, was quite a feat!

Parker received another patent in 1922 for a banjo with a wooden soundboard located below the skin banjo head, creating an internal sound chamber. The skin head was connected to the soundboard by means of a secondary bridge, and the tone could be adjusted by means of a wooden slider wedged between the soundboard and the dowel stick. Parker claimed the soundboard increased the sound and improved the tone of his banjos. As far as we know, none of these banjos with soundboards have been found.

And if that wasn’t enough, with John Henry on banjo, Dorothy on guitar, Hazel on cello and Marion and Mildred on mandolin or violins, the Calvert-Parker Co. was advertised as the most Artistic Musical Act in vaudeville. They played in vaudeville/movie theaters with names like the Bijou and the Majestic, opening for silent films. One program describes the act as “20 MINUTES OF HARMONY presented in an Original and Refined Manner by ARTISTS OF RECOGNIZED SKILL.” Marion and Hazel also performed violin and cello duets on WBZ radio down in Springfield.

With all this activity, one would think that John Henry Parker would have done quite well, and in many ways he did. He was a musician and a luthier, and was driven to create his own place in the music world. He designed, patented and built a unique line of beautiful fretted instruments. He started his own music school, and he performed and entertained on stage with his talented family.

Yet he remains a mysterious and obscure figure in the larger picture. His is not a household name generations later. People don’t pay thousands of dollars for his instruments today. His instruments are rare, and except with a few family members and the occasional collector, he has faded from memory. John Henry Parker died on July 8, 1929, at the age of 69. He’s buried in Woodland Cemetery in Keene, New Hampshire.

Joel Louis Eckhaus was born in White Plains, New York, on May 26, 1951, the son of Morris Eckhaus (a dentist) and Helen Weinstein (a former fashion designer). He spent his first 18 years in White Plains. He was pretty good in science and math, but wasn’t the most prodigious reader. He was always making things with his hands, and he liked playing music. His parents wanted more than anything for him to go to college, which he tried, but in the end…well, heck, why don’t I just tell you the story myself?

When I emigrated to the “People’s Republic of Burlington” back in the fall of 1972, I was your typical 21-year-old clueless hippie. I had already dropped out of college — twice. That spring I had hitchhiked with my rucksack, and my mandolin to Nashville, and traveled around to half a dozen or more bluegrass and old-time festivals as far south as New Orleans. I had never really been south of New York City except for maybe Florida (and that’s part of NYC), so it was a cultural experience. Old time, jazz, ragtime and country music got into my head.

I had been “working” at summer camps for room, board and not much money. My girlfriend was heading off to college in Burlington. That seemed like a pretty good destination, so I packed up my rucksack and my mandolin, and hitched north. September was pretty nice, but it got much colder in October. It snowed before Halloween. Money was running out. I needed a job, a place to live and a car. And luckily, I got work in a day care center, bought a ’66 Plymouth Valiant for $500 and found a three-room apartment in an old barn out in Essex with a roommate named Mike. Things were just settling down when I lost the job, the car turned out to need some work and the apartment wasn’t exactly heated (and it had the occasional rodent).

So, I was sitting around one day, unemployed, underheated, with my lousy, rusty car, playing my mandolin, wondering what the heck was gonna happen next, when the idea suddenly dawned on me that perhaps, I could…build instruments for a living. I liked to work with my hands. I had an ear for music. I had once made myself a nice case out of plywood wall paneling and pine to carry my Gibson mandolin on the road.

The word luthier was not exactly in my vocabulary yet. So I went to the library. Eventually, a plan emerged. I dropped back into college (thus returning to the grace and financial support of my parents), enrolled in a woodworking class one night a week and moved to town, to a four-room walkup at 3 S. Willard Street, about a block from 51 N. Willard, where John Parker had lived 70 years earlier. In fact, he would have walked by my building every day on his way to work at 230 College Street, not that I knew anything about him back then.

That summer, I studied woodworking at the Rochester Institute of Technology. I moved back to Burlington, to a four-room apartment (again within a couple blocks of Parker’s house) with three other guys, and started building a mandolin in my bedroom. We picked apples that fall, and started a band. Eventually I found work as an apprentice with Peter Tourin, a harpsichord and viol maker, down in Duxbury, Vermont. The job lasted for about two years, and I drilled enough holes and adjusted enough harpsichord jacks to really appreciate boredom. I also learned quite a bit about repair work. I was also playing with the Arm and Hammer String Band, a quartet with guitar, banjo, mandolin, bass and fiddle. We played concerts, dances, festivals, coffeehouses, bars, grange halls, old opera (aka vaudeville) houses all around New England, and beyond.

At one time, during my apprenticeship I thought that perhaps I might get a real job and teach woodworking. I looked around at schools in the area that offered such a degree, and took a drive down to Keene State College in New Hampshire. I had a tour of the woodshop, and was interviewed in the admissions office. In the end, I decided against it as the band was actually providing a modest living, and I thought I could make a go of it building instruments.

I had another girlfriend back then. She wanted to visit a psychic, this little old French Canadian farm lady named Luvia, who lived out in Marshfield. She could find things if they were missing, and she could tell your future. I went along for the ride. After my friend went in, Luvia asked me if I wanted a reading. She looked at my hands. She told me that I was an instrument maker, that I would live in Maine, and that I would make “historical” instruments (and that this girlfriend wasn’t gonna last). It all came true!

In 1976, I opened my own shop, Earnest Instruments, and moved back to Burlington, to Adsit Court, right around the corner from John Henry’s place on Willard. The name came from a customer’s Regal Octophone that he called Ernest. The Octophone was an unusually shaped octave mandolin that could be played in several tunings. I built a copy of it. My first orders were for two hammered dulcimers, a couple of five-string banjos and an Indian rosewood octave mandolin that looked remarkably similar to one of Parker’s Bandolas.

In the 1920s, the Calvert-Parker Co., John Henry’s family band with wife Dorothy on guitar, Mildred on mandolin, Hazel on cello, Grace on violin and John on banjo, performed throughout the northeast in opera (vaudeville) houses, schools, concert halls and radio. My band, the Arm & Hammer String Band, performed in much of the same territory, in similar venues, with similar instruments and repertoire, in the 1970s.

But then I heard a recording of a ukulele player named Smeck and my life took an abrupt turn. After one lesson, I left the band and Vermont in 1979 to study tenor banjo and ukulele in NYC with vaudeville legend, Roy Smeck, “The Wizard of the Strings,” a master musician and performer. This was my college education. For two years, I practiced those instruments everyday. For money, I drove a school bus, then worked in a boat yard and then in a 1980s “Nickelodeon factory” (more drilling holes). I practiced the ukulele and banjo at lunch just as Roy had done when he worked in a shoe factory in his early teens. While in New York, I also met tenor banjoist, Eddy Davis, and performed with his, New York Banjo Ensemble, a four-string banjo quartet, that played classical, ragtime and jazz music.

I moved to Maine in 1981. New York was a little “too close to home.” I met some new friends and we started another band, the Blue Sky Serenaders. I worked in a basement workshop with Dana Bourgeois, building and repairing string instruments. I finally graduated college in 1990 (my parents were so happy!) with a degree in vocational education and got a job teaching at Maine College of Art.

In the early 1990s, I started to use a pattern of black, white and red purfling on my instruments. It was to become one of my signature details on many instruments to come. Parker’s 1907 Bandola mandolin has a similar pattern of black, white and red purfling.

In 1993, while working at Dana’s new guitar factory, I built Big Red (the only Bourgeois cello guitar ever built!), my attempt to design an octave tenor guitar as an alternative to the mandocello. A Bandola Co. ad in the Cadenza lists a “Bandola ‘Cello” in the catalog. (If there ever was one, it hasn’t been seen). The ad also states that they’re the greatest instruments of the mandolin family ever manufactured. Parker clearly thought he had the next great mandolin of the 20th century.

In 1995, I designed and built a prototype solidbody electric mandolin that I called Little Red. It featured a sleek one-piece body/neck shape that cut away most of the upper bouts on a typical mandolin shape. The design is almost a duplication (if not a violation!) of John Henry’s 1894 patent. I also started using a pattern of black, white and red purfling on my instruments. It was to become one of my “signature details” on many instruments to come. Parker’s 1907 Bandola mandolin has a similar pattern of black, white and red purfling.

I’ve continued to build and repair stringed instruments, and currently live and work in SoPo. I’ve adapted several historical instrument shapes and details into some new designs and my own line of uncommon musical instruments. I’m currently working on a mandolin with a new shape and a cutaway that I think could be the next great mandolin of the 21st century. I’ve also continued to play mandolin, ukulele, tenor guitar and banjo. I have been a part of the now 40-year-old new vaudeville movement to bring live variety shows back to the old theaters and opera houses. Lately I’ve been teaching ukulele at workshops and festivals around the country, as well giving private lessons at my home.

You’d think with all this activity that I’d be doing pretty well, and I’m not complaining. I’ve had a steady stream of orders and my instruments are played and collected near and far. Let’s just say that I enjoy being able to do the things I love, and hope that I can continue to do them for a few more years.

It was serendipitous that, as a result of some obscure discussions about my Bandola mandolin that were archived on the Mandolin Cafe discussion board, I made contact with Scott Mann (grandson of Hazel Barnes, Dorothy Parker’s daughter) and George Crocker (grandson of Ruthven Parker Walsh), who have provided a wealth of details, documents, instruments and photos and filled in the many blanks about their great-grandfather, John Henry Parker. To them and to him, I give my thanks.

This article originally appeared in the Fretboard Journal #30.

Photographs by Scott Mann / Joel Eckhaus