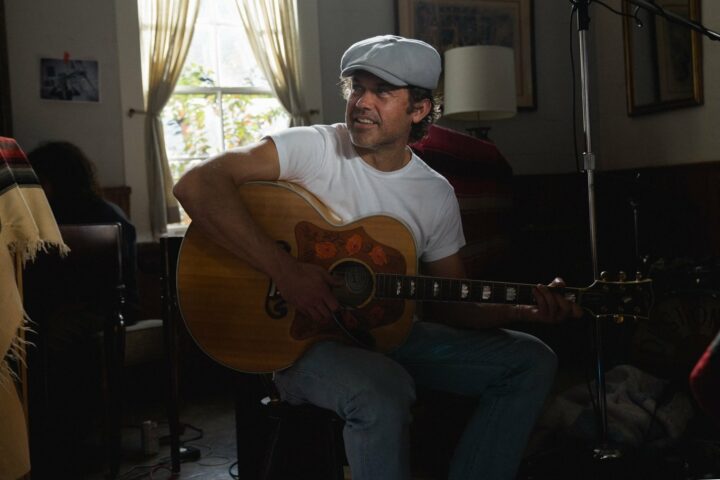

There’s this thing about our favorite guitar players and our obsessions with the instruments they play. Strong associations form in our mind–So-and-So is a Strat Guy and What’s-His-Name is a Vintage Martin Guy. Affection and admiration transfer freely–we like So-and-So because he plays our favorite guitar and we like that guitar because What’s-His-Name plays it. Some guitar players transcend it entirely, while others get heckled if they’re not playing a Tele. Meanwhile, luthiers love to see and hear their instruments in the hands of great players, for obvious reasons, both personally gratifying and potentially remunerative. What this leads to, now and again, is change–all of a sudden that favorite player of yours isn’t playing what you’re used to seeing that favorite player playing. This happened to us recently when Julian Lage stopped by the office, with Aoife O’Donovan and Chris “Critter” Eldridge but without his ’39 000-18. Julian, it seems, has spent the past couple years working with Collings Guitars on the Collings OM1 JL.

Although we’d seen the Collings video featuring Julian for their T (Traditional) Series, we didn’t know how deep this project went.

Collings Guitars, though still reeling from the recent passing of founder Bill Collings, just announced the OM1 JL, “moving forward with the same energy and drive [Bill] always brought to the shop.” We touched base with Julian, who told us the story…

Fretboard Journal: How did this whole thing get started?

Julian Lage: It actually got started, I’d say, probably two years ago, if not longer. It was a conversation that I had with Mark Althans over at Collings, who’s a dear friend of mine. I said, “Hey, could you make an OM-1A, but without polyurethane and with just a couple other things just to make it as like bare-bones as possible?” And he said, “Oh, that’s so funny you ask because we’ve actually started working on (what became the T Series for Collings).” And so what resulted is me going down to Austin several times having these long like four or five-hour sessions with Bill and Mark and Steve McCreary and everybody from Collings.

I’m trying to figure out what it meant to make a new guitar that got closer to what we love so much about old acoustics. And my argument which they–it wasn’t an argument–but the case to be made was that the Waterloos are just these stunning guitars. They’re, in Collings terms, you know, very simple, and yet they have so much life and so much immediacy to them. And I said, “Is it possible to have that with these other guitars in the same way?” Not to say that Collings don’t have that. It was kind of like I was looking for a guitar that would break-in immediately, and not feel like it stayed “beautiful.” And everyone understood this on a gut level. You know, they said, “Yeah, yeah, yeah.” But then it was like, “Well, how do you do that? What is that thing that players respond to?” So this set about like two years straight of trying to understand. I was looking at old guitars, comparing them. They built several guitars for me which just kinda went back and they said, “Okay, we’ve gotta start over, start over, neck profile, this and that.” And it was just a really beautiful experience. And so that greased the wheels for the T Series.

The T Series has a lot of features that came out of our discussions. But we all knew that that wasn’t the thing that I called about. I’m talking about a matte finish, let’s question what’s in the neck, pick certain different kind of types of woods of different weights and thickness and thinnesses to mimic old guitars. So, what resulted was this JL style guitar, and it’s really cool. I have two of them and they’re amazing. Anyway, that’s the story in a nutshell.

FJ: How much of this was about matching your vintage Martin 000?

JL: Well, it was similar but not totally the same thing. I love that 000 so much. One of the features that’s really interesting is it’s really light and has what I would consider almost a “phantom” low end. Like it’s not actually bass-y, but when you play it or record it, it sounds bass-y. I’ve felt this with a lot of old Martins, actually. You know the phenomenon where like a parlor guitar can sound really bass-y and beautiful. That was a feature that we definitely said, “Yeah, we gotta work on this.” Also, the neck profile is exactly that of the ’39 000. So that’s to the T just exactly the same neck with irregularities and all.

FJ: Is it the same scale or…

JL: No, it’s a long scale. That’s the difference. That was something I had been wanting to do when I called them a couple years back. I said I’m playing more solo, I’m going into drop D, I’d love a slightly longer scale length.

FJ: So it’s more of an OM than a 000…

JL: Yeah, it’s not a 000…It was an interesting thing because none of us set out to make it a [signature] model. And I think we all shared similar feeling that [signature] models–as cool as they are–often sport features that are so specific that you kind of go, “Well, that’s great for them and it’s cool, but now I have their name on my guitar…” Who knows if anyone would even like these features? I have to say, though, that the main thing is that it’s a very dry guitar. It’s not a shimmery guitar. It kind of sounds like a guitar that’s been played a lot, right away.

FJ: So, it really was a sound and feel kind of thing. It wasn’t just like you were going for just one or the other…

JL: No, no, no. And I always found the argument was like Collings has found a beautiful way to enhance the way guitars behave. You know, they’re loud, they’re clear, they’re focused, they’re easy to play. What’s not to like, you know? But the category that we were kind of trying to delve into is well, though that may be true, why are so many of our favorite guitars really irregular? Why are they unusual? What qualities do they have that allow them to take on the identity of the player over time. And basically, that was the main focus was let’s take out anything that would prohibit lots of hours of playing from putting a dent in this guitar, both literally and figuratively.

FJ: You mentioned you have two of them. Do they sound different?

JL: Very different. Yeah, they’re different, but they’re good in the same ways. That’s what weird. The other one has a wider nut. Frankly it sounds a little more like a Martin than the one I play. I don’t know what that means. I think it just means the relationship of the low end to the mid-range is a little more bluegrass-y. Like it just sound like driven and kind of steel-yin a really cool way. But it’s got this felt-y, kind of “thup-thup-thup-thup” thing all across the guitar, which I think the point of this model is, that it kind of promotes that thing which I think often happens on old guitars, especially once the top gets a belly, you know, and the bridge kind of starts to tilt.

The other day I was down and they had built one guitar, one body and five necks all with different innards. You know like some with truss rods, some with maple dowels, some with mahogany. And all of these different necks on one guitar, what was so interesting was that they all – there were some real misses which was actually really comforting because it helped us feel like we were on the right track with it. You know because there are ones where we’re like, okay, you take those qualities of a JL guitar and you put it with a neck like this, it just sounds dead as a doornail. Or, now it’s this light body with a heavy neck. You know, so it’s kind of a balancing act that is tough to predict because the whole point is a guitar that as you play it comes into its own, which is, you know, it’s been interesting to see how these have aged. I mean I’ve been playing mine since November, and then seriously with Critter for the last few months and it’s so good. It’s getting so good. It was great to begin with…the only interesting thing about it is I think if you played it and you expected it to be like shimmery and like perfect sounding, you might be surprised that it’s kind of – it makes you work a little bit more than, maybe, a traditional Collings. You kind of have to say, “Oh, shit, I’m playing it too hard,” or “Oh, no, I need to drive this string a little more.” There’s definitely an interactive element. But what I have to say that I notice is that everyone who I’ve showed it to plays it and has a thing with like, “Oh, interesting. What is this?” But they can’t put it down, you know, which is what makes me happy. They go, “Let me try this on it,” or Critter plays it, and he goes, “I never play guitars this small.” Then, you know, 30 minutes later he’s still playing it. That! That was the point, you know: a guitar that you just kind of don’t want to put down.

And, no small part of this was the outcome of Bill being so involved. I mean, he was really involved, and he is with every aspect of the company, but I think I was surprised that there would just be these marathon meetings with him where he would say, “Okay, when I started this company, I thought this is what had to happen. You’re telling me that people don’t always like that.” And it was a thing. I’d be like, “Bill, people love what you’re doing. What I’m asking about might not be for everybody, and I get that. I’m asking for something very specific that me and my friends might like.” And he was so open-minded. He said, “Okay, you know, great.”

It reminded me a lot of the stories I hear about the old correspondence with Martin when, you know, inventing the dreadnought with Vada [Olcott-]Bickford, or all these different kinds of revolutions that happened at the factory. It was like, there were players who come to them or write letters and say, “Hey, have you ever thought of making a bigger guitar?” you know.

Or I need a guitar that has a little more this or that, a little less that. It was very old-fashioned the way it came about. And I think we were all just so proud with how it came out that we thought this has got to be available to everybody else.

Oh! And that’s the last detail: The headstock has Bill’s original logo. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen them, but when he used to do the inlays himself back in the ’80s, on the like one-off Collings, the logo’s different. It’s really sweeter. It’s not as bold. I think Bill hated doing it. So, a lot of them don’t have the dot over the “i.” It’s like the dot is a pain in the ass to inlay.

And if you looked in the sound hole, it would only say OM1 JL.

FJ: Did you have to go down there and sign 100 labels?

JL: No, they do it themselves. It doesn’t have my signature, it doesn’t have my name. As far as anyone else knows, it’s the Jim Lauderdale model. John Leventhal is another one I thought would probably get a kick… But it’s all done undercover. It’s not about me. It’s more about Bill and the openness of the company to put their resources into something that’s kind of unusual and not for everybody, but, I think an important thing in the market that doesn’t totally exist. I think it’s a very cool thing, and I’m very proud to be a part of it.