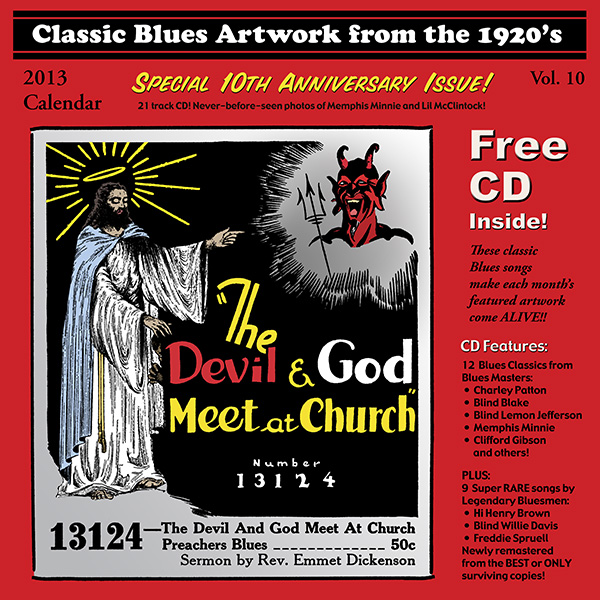

The days are short and the nights are long so it must mean it’s time for John Tefteller to release the latest edition of his Classic Blues Artwork from the 1920s calendar. Every year I think this is the year he finally runs out of great images from old blues ads and every year he still manages to amaze me. For 2013, Tefteller has turned up a couple of obscenely rare store fliers featuring Memphis Minnie and Blind Willie Johnson to go along with his usual assortment of of ads from Paramount, Victor and Columbia. And, like all the previous years, Tefteller has included a CD of the songs featured in the ads so you can spend the next year listening to the music of Blind Blake, Clifford Gibson, Charley Patton, Blind Lemon Jefferson and Buddy Boy Hawkins, among others. And, like he always does, Tefteller has managed to turn up some incredibly rare records that he’s included as bonus tracks. I had to call John Tefteller to find out what the story was with the latest edition of the calendar.-MJS

Fretboard Journal: The 2013 calendar has some amazing images, just like the calendars from previous years. I noticed that along with the old ads you usually reproduce, it looks like there are a couple of old record store fliers with some great photos of Memphis Minnie and Blind Willie Johnson.

John Tefteller: Isn’t that a nice photo of Memphis Minnie? We spent a lot of time on the restoration on that one. You know, when you go looking for photos, actual photographs of blues singers from the ‘20s and ‘30s and you quickly discover they don’t really exist anymore. You can almost literally count them on a couple hands. That’s not to say that these musicians weren’t photographed. They were. I have a theory that every single one of those blues singers that made records in the 1920s and ‘30s had a publicity portrait taken, either before or after their recording session. I’m convinced that they didn’t just record the musicians and send them on their way with no thought of how they were going to promote them. They were running advertisements in newspapers and they were making up fliers and posters when the records came out to promote them. So they had to take promotional photographs of all these guys. And I’ve had a number of people who are relatives or wives or children of these people who’ve said, “Oh, yeah, yeah, we used to have a portrait that was taken back then but we don’t know what happened to it. It’s gone, it was lost in a flood or a fire, or it got destroyed somehow.” So finding the photographs of the actual blues singers can be as hard or harder than finding the records.

FJ: Were these fliers originally handed out in stores?

JT: Yes. The Blind Willie Johnson flier, for example, is roughly a 5” x 7” piece of paper that was handed out in record stores. You would go in a record store and you would buy your favorite blues records. You would pay for them and then as you’re leaving, the clerk would hand you one of these little fliers and say, “You know, next time you’re in you might want to check out this guy. He’s pretty good.” And they’d give you a little flier with Blind Willie Johnson’s picture on it and a Columbia logo and a little bit of printed information. So that’s what that is.

FJ: You always include a CD that features rare recordings from the musicians pictured in the calendar as well as a few extra tracks. What goodies do you have for us this time?

JT: The first two bonus tracks are “I Believe I’ll Go Back Home” and “Trust In God And Do The Right,” from a Paramount record by Blind Willie Davis from 1930. For a long time, the only copy that existed of this particular record was a destroyed disc that was so bad that it was unlistenable. I was able to secure a really nice clean copy last year, and now both sides of it are available in really good sound quality. I think it’s his best record. The two tracks are gospel songs – gospel and blues were closely aligned at that time–and he’s a great guitar player, so you can hear some really great guitar work, and some really great vocals on those two tracks.

The same situation applies to the next two bonus tracks on the CD, which are by Hi Henry Brown, “Titanic Blues” and “Preacher Blues.” There was not a super-clean copy of this available until about a year ago. These two tracks sound better than they’ve ever sounded on CD. Brown was this great Saint Louis area guitar player from that Depression period. For some reason, I don’t think that the mainstream of America was ready to make songs about the sinking of the Titanic. Even 15 years after the ship sank, I guess they thought it was a little bit too depressing. But depressing goes quite well with the blues so I can see why a lot of blues singers sang about the tragedy. There were also quite a few country singers who did Titanic songs.

Along with these clean copies of rare records, we also include one that doesn’t sound quite so good. “Fancy Tricks,’ sung by Laura Rucker and backed by Blind Blake on guitar. That one’s quite noisy and a little bit distorted and it’s a little bit of a pain to get through it. The reason I included it, though, is because it was Blind Blake’s very last appearance on a record before he disappeared and died shortly thereafter. And it is not one that I believe has ever been reissued anywhere in any form. And so I thought even though this is the only copy in existence and it’s battered and it doesn’t sound that great, there’s enough people out there who love Blind Blake’s guitar playing who would appreciate being able to hear his last performance before he vanished.

FJ: What struck me about these recordings was how good the music was. The scarcity of the records has no bearing on the quality of the performance. Is every rare old blues record an undiscovered gem?

JT: I don’t want to give the impression that every single one of these things was a masterpiece back then. There are some that are pretty awful and they didn’t sell for a reason. But overall, there are some absolutely stunning, amazing blues masterpieces that have been almost lost to history simply due to the fact that there were very few purchases of those records. These records are so rare in some cases that there’s only one or two known examples that still exist. A lot of them were released in the middle of Great Depression and the numbers of records pressed and purchased then was really, really low. It was worse than anything going on in the music business today. And the numbers of records purchased by African-Americans, who were the poorest of all in the Great Depression, was the absolute lowest possible number of records. So, first of all, the record companies didn’t make very many of these to begin with because they were struggling, then they sent them out to the record stores and tried to sell them to an audience that had almost no money, and so very few copies were sold back then. The companies were pressing maybe 200 or 300 hundred copies, at most. And then the few copies that were sold, well, they are fragile, breakable records that are easily scratched or broken, and so to find one in good playable condition, after 80 years, becomes a near-impossible task. And don’t even think of going back to the record companies to try and get an original master– they don’t exist. They were thrown out, destroyed or sold for scrap metal. And so us record collectors have to kind of go out into the world and search these barns, and attics, and flea markets, and garage sales, and private collections, until we can come up with some of these titles, and sometimes when we find them they’re completely battered and unusable.

FJ: I see that you included two different takes of Charley Patton’s “Some These Days I’ll be Gone.”

JT: I’m a big fan of Charley Patton. He’s my number one favorite from that pre-war blues period. But, honestly, that particular record is not one of his absolute best records. It’s probably head and shoulders above many other records from the time period. But it’s not Patton at his best. But the reason it’s included here is for a couple reasons. One, I had really nice artwork for “Frankie and Albert,” the A-side of that record, that I wanted to use in the calendar. And two, there were two surviving takes of “Some These Days I’ll be Gone,” which is unusual for blues tracks from this period. If you listen to them side by side, there’s not a dramatic difference in the two tracks. One is a little bit longer than the other so you get a little bit more guitar action. But it’s interesting to see an example of why something was rejected and then why something was actually issued by the company. And of course, anything new by Patton, even an alternate take, is well wanted by most of the people that collect blues music out there.

FJ: There are also tracks by some players I’ve never heard of before. “Snatch it Back Blues” by Buddy Boy Hawkins is really good. What can you tell me about him?

JT: Nothing. Buddy Boy Hawkins. made four or five records for Paramount in the late 1920s and they’re all good. And there is absolutely nothing known about him. He’s one of those people that sort of showed up at a couple different recording sessions, made some records and then he just disappeared.

FJ: Is that same story with Freddie Spruell?

JT: Pretty much. He was a very obscure blues guy who did a number of records that have been reissued over the years. This particular one, “Ocean Blues,” backed with “Y.M.V Blues,” was actually unknown. A guy contacted me a few months ago and he said he had this record and he couldn’t find it listed anyplace. That was odd because it’s a Bluebird record, which was part of RCA. You’d think it would have turned up in catalog or sales sheet, but there was no listing of it anywhere. Anyway, he played it for me on the phone, and I thought, “Oh, this is really good.” So I wound up buying the record from him and both sides of it are on this CD. It was recorded in 1935, and features Washboard Sam. “Ocean Blues” sounds like it may be a another song about the sinking of the Titanic, although Spruell doesn’t mention the ship by name. The YMV in the song “Y.M.V. Blues” refers to the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railway.

FJ: Thanks for your time, John, and good luck with your searches.

JT: You’re welcome.

(You can read my interview with John Tefteller about the 2012 edition of the Classic Blues Artwork from the 1920s here.)