Above photo: ©2009 Twangbox®/Bradley Klein

Andy Statman is a legend amongst bluegrass aficionados, but that barely scratches the surface of his depth. While fretted instrumentalists follow Statman for his mandolin playing – he famously used a 1923 Gibson A-2Z for years and is currently utilizing a Kimble F-5 – he’s also a legend in the world of klezmer clarinet, world music and jazz. Earlier this Spring, Statman released his latest project, Monroe Bus. Originally meant to be a collection of interpretations and improvisations of Bill Monroe tunes, the album evolved into a completely different beast. We decided to check in with Statman about this eclectic record of original mandolin tunes and how he recorded it.

Fretboard Journal: First, off, this record is amazing. But it’s not really a tribute record to Bill Monroe, is it?

Andy Statman: Well, no. If I did a tribute to him specifically I’d probably play his tunes. This is more of a tribute to the spirit of what he did, in some ways.

I was going to do a record of improvisations on Bill Monroe tunes and I just wound up writing my own tunes. That’s sort of where it went. But Bill Monroe is the biggest influence in my playing, the way I use my right hand. And my understanding of tone production. So Monroe is definitely sort of always there hovering in the background, with a bunch of others, as well.

FJ: Talk to me a little bit about that right hand. What sticks with you from Monroe? And how has that affected your playing?

AS: Well, back when I was learning how to play bluegrass, I studied Monroe, Jesse McReynolds, Bobby Osborne. I sort of trained my voice to be able to sound like them, to emulate their tones.

So it’s really an understanding of tone, but the way Monroe uses his right hand to play notes, to play tremolo, to play rhythm, there’s a very specific sound that has a real sort of intensity to it, that I always liked. Not that others don’t have intensity, but in Bill Monroe stuff, I found something that was a bit more universal that I could apply to a lot of other things.

His right hand is always going for feeling. And expressing those musical ideas, a depth of feeling. I was and still am very drawn to that approach.

FJ: There are thousands of mandolin players who have bought an F-5 or F-5-style mandolin to try to capture that tone. Yet you also famously played a Gibson A-style for many years. Is it really all in the hands?

AS: Yeah. As you know, I have played a F-5 style mandolin for the last probably 10 years. It’s a matter of the neck, rather than the sound. I could play like Bill Monroe on the A [style mandolin] I had and people wouldn’t know it was another old mandolin.

It’s really the right hand, it’s really understanding how to use the right hand to produce a certain tone…

FJ: Got it. And where do most beginning mandolin players mess that up?

AS: Well, there are lots of different schools of mandolin playing, so it really depends on what style of music you want to play. The main thing is to emulate the people whose playing you like. You want to be able to know and play with the left hand the way they play, but the right hand is really a much bigger deal than the left hand. You really need to start to understand what tone is and how tone expresses feelings and ideas. You really need to emulate the tone of the people who you want to sound like, rather than just playing the notes their playing. You really need to understand how to get that sound and that feeling that’s drawing you in.

It’s really pretty much about sound and how you use sound, as opposed to just musical ideas. The tone is a very big musical idea and expresses a lot. That’s why we might like certain singers who have incredible voices, even in styles we’re not familiar with, if the sound of their voice is great. Or clarinet players or saxophone players, or trumpet players or violinists, for that matter. It really all has to do with tone.

In any style, you want to learn the tonal language of the style. Tone production is really important. Once you can do that, you begin to use it on your own.

I had a number of different models in bluegrass whose tones I was able to emulate. Each person is an individual, but, in particular, when you’re going back to the founders of the bluegrass mandolin, that would be Bill Monroe, Jesse McReynolds and Bobby Osborne. And then the people after them like Herschel Sizemore, Frank Wakefield and John Duffey. They all started to develop their own understanding of tone based on what they were feeling and what sounded good. Each had a bit of a different tone conception. Bobby initially came out of the Bill Monroe thing, but developed his own wonderful unique style.

Tone is all the right hand. It’s like a voice box for a singer or, for a woodwind player, it’s the embouchure. It’s what you really need. And with really good players, you hear one or two notes and you understand who it is just by the sound, let alone the musical ideas or the way thing are being played.

FJ: You are, by far, one of the most soulful mandolin players. I can’t help but think that your family’s singing background and your time with [klezmer clarinet legend] Dave Tarras must get distilled into your mandolin playing.

AS: Of course. I’m one person, so whether I play a clarinet or mandolin, it’ll all there.

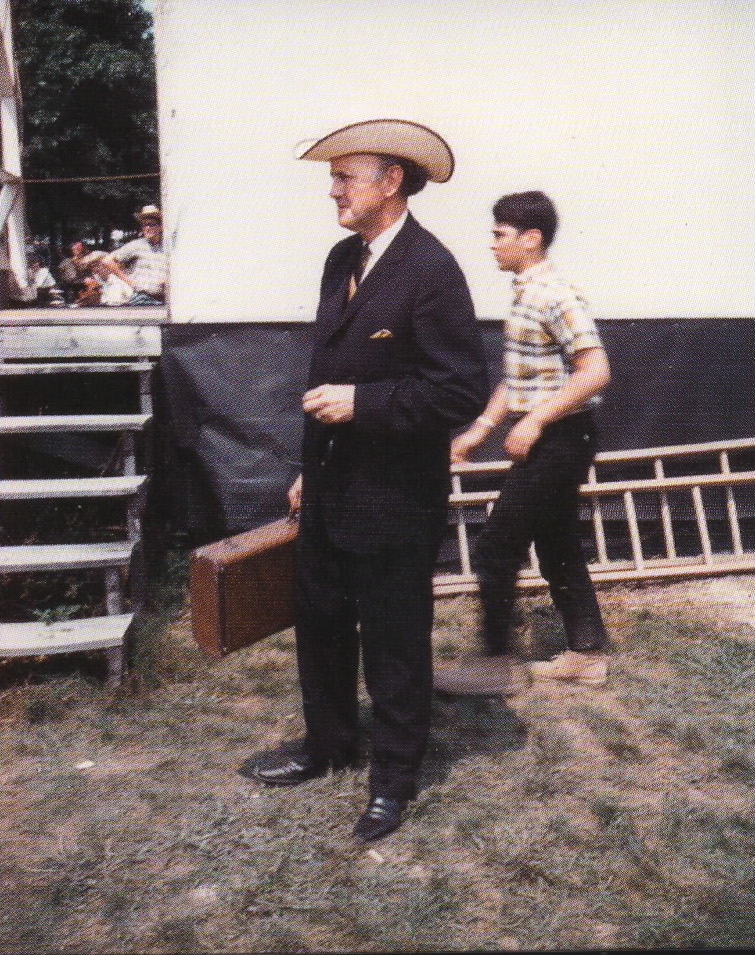

FJ: There’s a pretty amazing photo of you alongside Bill Monroe in the liner notes for this CD. Can you paint a picture of the day that was taken?

A 16 year-old Statman following Bill Monroe. Photo: Fred Robbins

AS: I didn’t even know that picture existed! At the exact time we were putting together the jacket for the record that picture surfaced. A friend of mine took a bunch of pictures of that festival and posted them. [Another friend] said, “That’s Andy,” and he sent it to me. It surfaced at the exact right time.

That was 1966, I believe, at the second Roanoke Bluegrass Festival. Pretty much everybody was there in bluegrass, more or less. And what was most exciting to me was that there were going to be these reunions of great bands that Monroe had with past players. I remember Rudy Lyle was there; Sonny Osborne and Mac Wiseman were there. There was a band they were going to put together with Bill Monroe, Don Reno and Mac Wiseman. It was a pretty amazing thing. These guys were at the height of their powers back then.

I’d gotten into bluegrass when I was about 11 or 12 years old. I started out with guitar and then banjo. So I had been playing mandolin for a little over a year then.

All of these guys were like my heroes. In that picture, I was probably freaked out to be so close to Bill Monroe and trying to very stealthily walk away [laughing].

FJ: How much longer did it take for you to muster up the courage to actually approach Bill Monroe?

AS: I met Bill at one of Tex Logan’s picking parties and barbecues in the summer. It had probably happened earlier that [same] summer. I was just so nervous. He was very, very nice, and very kind to me. I didn’t even want to play but I was sort of forced to.

FJ: Did you ever study with Bill or ask him for playing advice?

AS: I didn’t study with Bill Monroe. I just had a casual relationship with him, but I did study with David Grisman.

FJ: How much older than you is Grisman?

AS: David is maybe five years with in my age. When I went to see him, I’d just gotten a semi-roundback mandolin. I’d been playing guitar and banjo before that, going down to Washington Square and playing in bands and stuff. The sound of the mandolin really sent me. He really gave me whole lessons, just organically, on aesthetics. You’ve got to listen to Bill Monroe…

He told me to bring a reel-to-reel tape recorder, because he had an archive of hundreds of live tapes and tapes of 78s and 45s, which you just couldn’t get back then. He said, “Why don’t you record this and this and this, lock the door when you leave, and give me a call when you need another lesson.” I was there for about another two, three hours recording stuff. I tried to figure out what I could, I played hooky from school and I spent 10 or 12 hours a day trying to learn solos note-for-note. At first it took a long time. I eventually got to the point where I could hear a solo and know what key it was in by the way a person was playing. I would learn if Monroe did five tremolo strokes or seven tremolo strokes, because I really felt it really made a difference in the expressiveness of what he going for. You know, it was a spontaneous thing, but it wasn’t a random thing. I got into it very microscopically. After about two months, I called up David [for another lesson] and, he said, “Come on down.”

In the course of about two years, I took about five or six lessons from him in that style. It really gave me the keys to the highway. I understood how to try solos, I understood how to go about learning the musical language and I understood how important tone production was and how to go about getting it. I began to understand how to play a melody, ornamentation, how to improvise… just a whole bunch of different skills.

Things sort of moved on from there, but David was really my primary teacher in terms of giving me a real sure footing in how to be a musician. And certainly an understanding and having a sense of aesthetics and appreciating people like Bill Monroe. So, when I was down there at that festival, I had already drunk from that well a lot and was pretty aware of what was going on.

It was just a real joy for me to be down there, playing music out in the fields with different people. Joe Greene was out there; I played with him and a bunch. Jimmy Martin would be singing out in the field. It was really a wonderful, affirming experience. And everyone who was there was just completely elated. Everyone left there so inspired and so high from the music.

FJ: Your musical journey is one of the most fascinating ones I’ve ever heard, from bluegrass to klezmer to free jazz. What are you listening to right now? What’s on your stereo?

AS: Well, let’s see… I listen to a lot of stuff. I go through different things. I’ve been listening to a lot of Coleman Hawkins lately actually and a bunch of Wanda Jackson. It’s a wide array of music. And some Bill Monroe and the Osborne Brothers. I’ve been listening to some Ecuadorian music recently, some of the great guitarists from down there. I just listen to lots of different things. Everything I hear I want to learn, which is just quite impossible. Some of them I do get around to learning… or trying to learn.

FJ: Tell us a bit about the making of the Monroe Bus record. Where was it recorded?

AS: I originally thought it was going be a record of Monroe tunes. I wound up writing all these tunes, some of which are extensions of his tunes, some of which where you may not see a connection, but it’s still sort of there. I’ve been working with Larry Eagle and Jim Whitney steadily for the last 20 years. So we have this certain incredible communicative thing happening. We play a tune, we have no real arrangements, just through eye contact or gesture or whatever, we all know what to do. It’s really wonderful.

The previous record we had done with Michael Cleveland and I thought he’d be a natural for this. We recorded at a place called Acoustic Sound in Brooklyn here. We brought Michael in for the basics and recorded 23 or 24 songs. When the record was finally mixed, we just picked 12.

Michael can really pretty much play anything he really wants to. He’s a wonderful person and a fantastic musician. He really knows just what to do. Those were the basic tracks and then we brought in this really amazing keyboard player named Glenn Patscha, who can play a number of different root styles, as well being a good jazz player. So we had a Hammond B-3 in there, as well as a piano. He also had a pump organ. We brought in Michael Daves for a few tunes, a friend of mine who plays Azerbaijani music and a coronet player to play on a few tunes.

I used to like to do records pretty much live. In the last two records, I began to see the advantage of Pro Tools and what it affords you as a composer. I was able to hear the tunes over a period of time and decide that I wanted to add sections or delete sections, or add this thing or that thing. As a compositional tool, it’s absolutely fantastic. I just love it. Years ago, it would have gone against my whole aesthetic of doing everything live.

FJ: Did you use the Kimble mandolin for the whole record?

AS: It’s a great mandolin, yeah. It’s from July, 2014. I had played another F-5 and then I traded him a two-point and then I traded that for this. It’s just a great mandolin. It records really well.

FJ: Do you mic it differently than you did your old A-style Gibson mandolin?

AS: When I record, there are two problems. One problem is that I get into the music. I move around, so that’s a problem with the miking right there, particularly when I’m recording. A larger problem is that I hum along, sometimes quite loudly, when I play. So the engineer was able to set up twin microphones, so that it would sort of somehow cancel out a lot of the loud humming that I can do sometimes…

I remember one time when I recorded with Vassar Clements, it was back in, like, 1966 or something like that, and we were sitting, and then he said, “What’s that, what’s that?” And I said, “That’s just me, singing along.” He was cool with it; he just wondered what it was.

I don’t really mind it. But he had a particular way of miking it so it canceled out a bunch of that stuff. He used two different Schoeps mics to record me.

I’m not sure what I’m humming, but some people have told me that I’m basically humming either the melody or that when I’m improvising I’m humming. It’s really an unconscious thing to me.