“You mean you boys’ve come all the way from San Francisco to Deep Gap just to see Doc? Well, dang, that’s really somethin’!”

It was 1966 and my friend Mike Reed and I were on a pilgrimage to visit the legendary Doc Watson in his home town of Deep Gap, North Carolina (population 1,863 today, a fraction of that in 1966). We had just gotten off the daily Greyhound that wound east on U.S. Highway 421 from Bristol, Tennessee through the Appalachians. There was no bus station in Deep Gap, but the bus driver would drop passengers off on request.

The first thing we saw after we got off the bus was Watson’s Garage, on the highway. We knew we must be getting close.

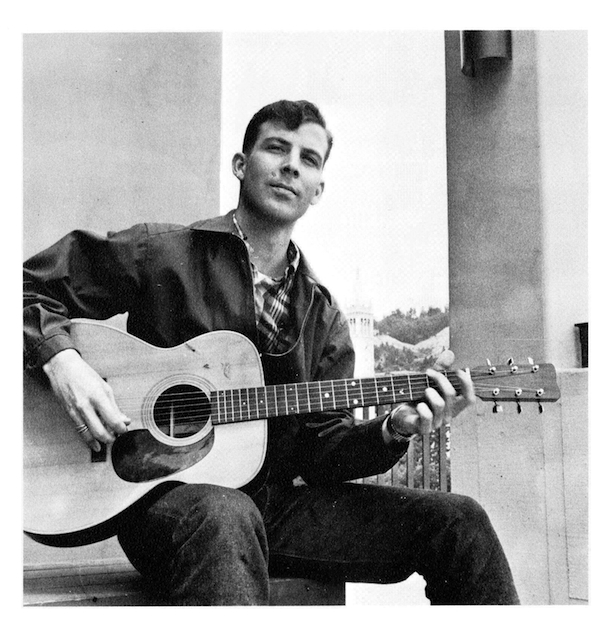

Author John G. Wagner in 1968, two years after his roadtrip to meet Doc Watson.

I had succumbed to the Kingston Trio in high school and discovered bluegrass guitar and banjo in college. I grew up in a suburb in the San Francisco Bay Area and I was about to begin my junior year at the University of California, Berkeley. Like most other folky musicians in the mid-1960s, I had a full repertoire of tunes by Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, and Tom Paxton with lyrics like “I’m goin’ down that long lonesome road, babe,” and “I can’t help but wonder where I’m bound,” and “I might strike it lucky on a highway goin’ west… with my hands in my pockets and my coat collar high.” I’d read Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and Woody Guthrie’s semi-autobiographical Bound for Glory, where hitchhiking and hopping freight trains were often good ways to go long distances.

All these influences convinced me there was an exotic “real” America which could offer experiences and understanding which could not be gained from mere college study or work or any transportation which had a timetable. As a personal challenge and as an education, I wanted to live out the coffee house fantasies and see the country from a hitchhiker’s perspective.

I’m still amazed I convinced my parents that a hitchhiking trip around the country was a fine idea. Like a lot of servicemen during World War II, my dad had hitchhiked when he was stateside and maybe that made hitchhiking tolerable. And maybe they, like me, wanted me to have some life experiences outside of the usual bounds of suburban California and to see more of the country. In any case, they agreed, on the condition that I phone home (collect) every Sunday. It was a deal!

And so I began planning my trip with the Bob Dylan/Tom Paxton “gotta bag on down that long ol’ road” checklist: I took a banjo, stuffed a sleeping bag and some other basic camping gear and clothing into a backpack, got some maps and I was ready to go.

Everything east of Houston was going to be new territory for me. Conveniently, I could hitchhike with my parents for the first leg of the trip, for they were going to East Texas to visit relatives. They dropped me off on a state highway that led to San Antonio, where a friend was going through Army basic training. Then I’d aim for New Orleans, then south Florida to visit an uncle. I wanted to see Nashville, Williamsburg, Virginia, Washington, DC, New York City, Niagara Falls, Detroit and a lot of middle of the country en route home.

And somewhere along the road, I wanted to visit Doc Watson, everyone’s flatpicking idol in 1966 and since, in Deep Gap. And in my youthful enthusiasm, I just naturally assumed ol’ Doc would just love to have a fan from across the country drop by his house.

But in 1966 there was a major threat to safe hitchhiking (oxymoronically speaking). The Civil Rights Act had passed in 1964, but some people involved in voter registration drives and other social activism were getting killed in the Deep South, where I was planning the first few weeks of my trip. I did not want to miss my Sunday calls home. I decided I needed some protective coloration when hitchhiking – a short haircut, Madras-style button-down Sta-prest shirts and a fairly tidy, clean-shaven look overall. Who would want to harm a banjo-toting college kid with a big smile and his thumb out? And isn’t that just the kind of guy you’d like to give a ride to anyway?

Nonetheless, I thought having a friend on this trip would be a very good thing. We could share the experiences and provide some mutual protection, just on the off-chance that not everyone was as cordial and helpful as Kerouac’s or Woody’s on-the-road people. A high school pickin’ buddy, Mike Reed, thought the hitchhiking trip would be fun, too. He was going to be in Ft. Knox, Kentucky with the Army ROTC for part of the summer. We agreed we’d meet at the steps of the Grand Ole Opry’s Ryman Auditorium in downtown Nashville on the afternoon of Sunday, July 17, 1966. He’d bring a guitar, so we could drag out the bluegrass whenever warranted (and maybe a few times when it wasn’t). We’d visit Doc Watson and continue on for the rest of the trip together.

Hitchhiking to Nashville went well. Texas was the easiest state to hitchhike in by far. Louisiana was the worst – I ultimately had to take a Greyhound to get to New Orleans. There I got a job for a week, running a ride at the now-defunct Pontchartrain Beach Amusement Park at $1 an hour. That doesn’t sound like much, but my room at a skid row hotel on Camp Street only cost $13 a week and I had some really interesting neighbors. I had to step over the derelict in the doorway most mornings. Yep, new experiences, all right.

After New Orleans, I kept hitchhiking east. I stayed at boarding houses and YMCAs when possible and slept behind the bushes on church lawns otherwise. I tried to convince the police in a couple of small towns to let me sleep in an empty jail cell – they said no, they didn’t want the liability. A couple of musical families took me in because of my banjo. I thumbed through Mobile, Panama City, Ocala and Orlando to Miami Beach, then north to Cape Canaveral, Columbia, South Carolina, and Asheville, North Carolina. I was worried I’d be late, but I connected with Mike at the Ryman Auditorium on the late afternoon of July 17, just as we’d planned.

As an extraordinary bonus, Mike had a friend-of-a-family-friend in nearby Shelbyville, whose name I believe was Bob Brannan. Bob was connected to the music business in Nashville and knew a lot of country stars and sidemen. Not only did he give us a comfortable place, he provided a unique tour of Music City. He took Mike to the Grand Ole Opry on Saturday night, before I arrived. Together we met Charlie Louvin a couple of times later that week, for he was performing from the back of a flatbed truck as part of a local congressman’s re-election campaign. We were in the audience at the local TV broadcast of theLittle Jimmy Dickens Show. Mike commented that Jimmy’s hat was way bigger than he was. We met him and some of his band after the show, including pioneering steel player Jerry Byrd. I remember noting that Byrd was dressed differently than most of the Nashville Cats we’d seen. Rather than Western-styled duds, he preferred natty casual slacks, shirt and shoes that would have worked in hotel lounges in Miami Beach or Hawaii, where he later moved. We met songwriter Harlan Howard and Bob took us to a music party with Sam McGee, of the McGee Brothers, at a friend’s home.

Bob knew the owner of a new guitar company in Wartrace, Tennessee called Gallagher and took us for a tour. As I recall, Wartrace was about two blocks long, with 19th Century brick buildings. The shop was in an old storefront on the main street. We tested some of their dreadnought guitars and were certainly impressed. A couple of years later, Doc began playing Gallagher guitars almost exclusively. Our insider’s tour of Nashville was an excellent prelim to the main event, visiting Doc himself.

In true contrast to hitchhiking, Bob had a four-seat Cessna and flew us east from Shelbyville to Bristol, Tennessee, where we could catch the eastbound Greyhound that went through Deep Gap once each day, headed for Winston-Salem. Soon we were among the dozen or so passengers on the morning run that wound through various small Appalachian towns. Our conversation with the bus driver went something like this:

“Would you let us off at Deep Gap? We want to visit Doc Watson!”

“Sure thing, boys. Yeah, I see Doc all the time. He’ll stand by the roadside with his guitar and a suitcase when he’s heading for a concert or somethin’ up North. I’ll get him to Winston-Salem and make sure he’s on the next bus he needs. He’s a real nice feller.”

“Do you know if he’s in Deep Gap at the moment, or do you think he’s traveling?”

“Well, I brought him back home a week or so back and, as far as I know, he’s still there.”

YES! In those pre-Internet days, it was hard to determine an entertainer’s schedule, so we really had no idea if he’d be home or not. We figured we’d take a chance, since we had to head east anyway.

After a couple of hours, the bus driver called “Deep Gap” and pulled to a wide spot in the road near a motel. We retrieved our packs and instruments. He said he’d be driving through Deep Gap the next day at about the same time and wished us luck in finding Doc.

We spotted Watson’s Garage across the highway, a quarter mile east. We walked in with our packs and instruments and introduced ourselves to the owner. We asked him if he could help us find Doc Watson. He said he was one of Doc’s cousins and, as noted, he was pretty amazed that a local guitar guy could attract visitors all the way from the San Francisco area. He called in one of his employees and his wife to meet the exotic visitors from California.

He pointed to a dirt road across the highway from his shop that rose into the hills. He told us Doc and his wife Rosa Lee lived about a quarter mile up that road, but he’d seen them drive away about 20 minutes earlier. He suggested we go to the motel where the bus had stopped and said he’d call to let us know when Doc and his wife returned. He even phoned the motel to alert them we’d need a room. I suspected there was no great rush for rooms on a weekday morning in Deep Gap, but we appreciated his consideration.

We got the room and about 45 minutes later, the phone rang. It was Doc’s cousin – Doc and Rosa Lee had returned. Mike and I walked down the highway a quarter mile or so and then turned up the road to Doc’s house. We had enough temerity to drop in on Doc uninvited, but definitely not enough to bring our instruments.

Doc’s home was a modest, tidy wooden house with white lightweight concrete shingles on the outside walls and a dark composition shingle roof. There was a screen door on the front and the door and window frames were painted black, as I recall. Flowers were planted in the front and there was a barn and a large garden in the back. We knocked on the door and Rosa Lee answered. We introduced ourselves, told her where we were from, said we were serious Doc fans and would it be possible to meet Doc? She graciously invited us in and called to Doc to join us.

And there he was – our guitar hero, shaking hands with us and asking us to have a seat in his living room. He asked about how we happened to be so far from home and we told him a bit about our travels. Mike and I had seen him perform several times and so we complimented (well, gushed) about how much we appreciated his music. He thanked us for our comments and seemed pleased that we enjoyed his music. With Deep Gap being so remote, I remarked how difficult it must be to get to distant gigs and I recounted the bus driver’s story of picking him up on the highway. He said, yes, it was a bit difficult, but he got around pretty well. As a testament to his independence, he said he did a lot of the gardening in the large plot in the back – and there were indeed a lot of lush-looking vegetables growing out there. He then pointed to a cabinet where he kept his stereo gear – he said he had built that and the wooden speaker enclosures. He had gotten some woodworking training at the state school for the blind that he attended. I thought at the time I was SO glad he hadn’t damaged a finger in the process, for all of our lives would have been poorer, but the speakers and cabinet were nicely done.

I asked him about how he played “Deep River Blues” and he said, “Well, let me show you.” And he did. He played that, “Little Sadie,” his signature “Black Mountain Rag” and three or four other tunes for us on his guitar and banjo from his first solo album. A personal concert from Doc Watson in his living room – how much more can you ask of life?

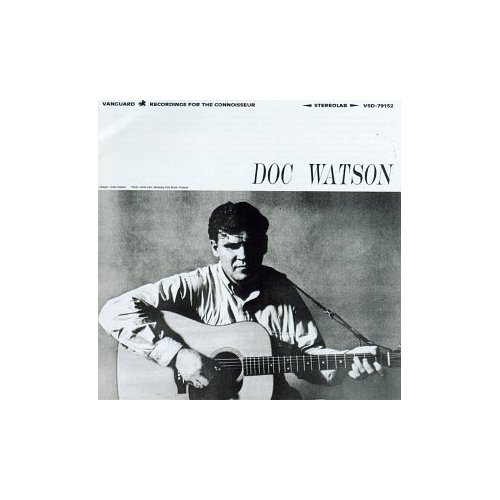

We had been there about an hour, so we started making our exit, with profuse thanks, best wishes and promises to attend his concerts. We thanked Rosa Lee for her hospitality and were leaving, when she said in a slightly commanding tone, “You boys do want to buy Doc’s album, don’t you?”

“Uh, yes, ma’am, absolutely.”

“That’ll be five dollars each.”

“Yes, ma’am. And thank you.”

So both Mike and I both got copies of the Doc Watson album that were marked “NOT FOR SALE” and were handed to us by Doc himself.

Just as we were leaving, a car pulled up and a lanky, dark-haired teenager got out. Doc introduced us to his son Merle, who he proudly said was learning to pick a bit. As Merle’s later music career brilliantly showed, he certainly seemed to have learned a few things from his old man. At the time, however, Merle was a 16 year-old. The last thing most 16 year-olds care about is meeting strangers they’d never see again, but Merle tolerated us enough to mumble “hi”, nod and shake our hands before he headed inside. We left with our great thanks to the Watsons for all their hospitality.

So Mike and I walked back to the Deep Gap motel and marveled at how amazing the whole day had been. The next morning, we stood at the wide spot in the road and flagged down the Greyhound. Our driver from the prior day asked how our visit had gone and we told him what a marvelous day we’d had. We all agreed Doc was a truly nice fellow as well as a superb picker.

Although Mike and I had some great experiences on the rest of our trip, the visit with Doc was the absolute highlight. We hitched our way north, visited some interesting places and met some nice (and a few not-so-nice) folks along the way. In New York City, we got to the nexus of the 1960s folk music world, Greenwich Village, where found a flophouse hotel near Washington Square Park ($1.74 a night – and you got what you paid for, but it did have an elevator operator in a seedy-looking uniform). We played some tunes in a coffee house or two, but we never encountered any of the famous players there. We crossed into Canada at Niagara Falls, heading toward Detroit. Mike had to get back home and so we split up when I stayed in Simcoe, Ontario to work as a tobacco picker for a few days (yes, there’s a small area where they grow tobacco there. The pay was good, but it was absolutely the hardest, most punishing work I’ve ever done). I made it home a couple of weeks later, with nothing to compare to Nashville and Deep Gap as memorable musical experiences.

So now, 45 years later, Mike and I still get together to play music (mostly jazz and swing) and for occasional trips (with paid-for transportation). Did I encourage my own two sons to discover America as I did? Absolutely not! I barely even mentioned my hitchhiking adventure until they were in their 20s. In the post-Jeffery Dahmer era, hitchhiking is about the last travel mode I’d recommend now.

The author (on guitar) with his travel companion, Mike Reed. Circa 1980.

Watson’s Garage moved to Boone, North Carolina in 1972 and is now David Watson Automotive. Merle tragically died tragically in a tractor accident in 1985. The annual MerleFest in Wilkesboro, North Carolina was created to commemorate his life and music. And Doc himself passed away yesterday, on May 29, 2012, at the age of 89. He had just performed a set of music at MerleFest the month prior.

Today neither Mike nor I can believe we were so clueless and naive as to think any performer would welcome an intrusion into his home. We continue to appreciate the gracious Southern hospitality that Doc and Rosa Lee offered the young strangers on their doorstep. Our visit to Doc Watson remains a highlight in both our lives and we thank him for a lifetime of superb music.

This memoir is dedicated to my music buddies from the mid-1960s into the 21st Century: George Ball, Frank Ford, Richard Johnston and, of course, Mike Reed. Thanks, guys! –JCW