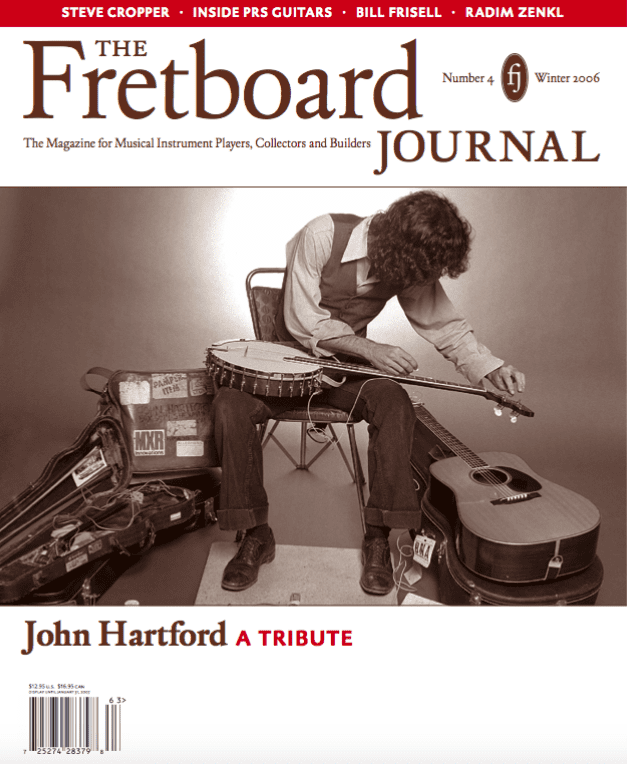

John Hartford and author Skip Heller.

When I was a little kid, any television show that featured someone playing a guitar or a banjo was appointment viewing. I was born in 1965, which means that the best time to spot pickers was Sunday night, and the best place was the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, which routinely featured top-notch players like Mason Williams, The Who, Ravi Shankar, Ike & Tina Turner, Judy Collins and Donovan. (I also thought Tom and Dick Smothers were amazing and that Pat Paulsen was a genius.)

In 1969, the Smothers’ show was replaced by the Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour, which was just as good. Both shows featured a laconic, deep-eyed banjo player named John Hartford, who had already made his mark as the writer of “Gentle on My Mind,” which was a huge hit for Campbell in 1967 and the theme song for his TV show. Hartford’s playing was spotless and creative, but I was drawn to the warmth of his voice and the quirky humor of many of his songs.

When I first became aware of John Hartford in 1969, he had already released seven albums on RCA, had an eighth in the can and was about to break up his touring band, Iron Mountain Depot. I didn’t know any of that at the time, though. I grew up in Philadelphia, and my world was simple when I was young. Basically, it revolved around the Beatles on WIBG and James Brown on WHAT. I never heard John Hartford on the radio but I got an extra dose of his music when my parents bought his album, Gentle on My Mind and Other Originals. I liked it so much that when I got five bucks for my fourth birthday, I used it to buy Hartford’s second album, Earthwords & Music.

Later, after I had met John Hartford and became his friend, I learned that his first five LPs were recorded in Nashville and produced by Felton Jarvis, who indulged John’s poetic leanings and kept his voice and banjo in the center of the music. Even when there were strings or horns up in there, Jarvis knew that it was Hartford himself who made a John Hartford album interesting.

John Cowan Harford (the “t” was added by Chet Atkins when he signed him to RCA) was born December 30, 1937, in New York City. His father was a doctor, and within months of the boy’s birth, the family had moved to the St. Louis area, right near the Mississippi River. The boats captured the young boy’s imagination, an inspiration that was deepened by his fifth-grade teacher, Ruth Ferris, who had the wheel and pilot house of a packet boat called the Golden Eagle moved to the school grounds after the boat wrecked. John Hartford decided his life would be spent as a riverboat pilot on the Mississippi and he subscribed to the Waterways Journal, the weekly bible of river navigation, whose writers included Steamboat Bill, Jimmy Swift and, most important to John, Capt. Fred Way.

“My first choice of profession was to be a riverboat pilot,” Hartford said to me in a phone conversation years ago, “but then I heard Earl Scruggs and it”—he made a clicking sound over the phone—“snapped the bough.” In a world where square dancing, old-time fiddle tunes and the loping sound of clawhammer banjo were the norm, the three-fingered banjo style of Earl Scruggs (as heard in Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys) had an impact we can only marvel at today. Perhaps the most reasonable modern comparison would be the release of Eddie Van Halen’s “Eruption” in 1978. Think about it: Everyone heard “Eruption” on Friday and was two-hand fretboard tapping on Monday. Scruggs had the same effect on string-band music in 1944, and that hard-driving sound inspired Hartford to learn the banjo.

But banjo wasn’t the only instrument that called to him. The St. Louis area was rich with string-band music, and Hartford’s parents liked to go square dancing. Kids were generally allowed at the dances, and young Hartford heard some great regional fiddle players, most notably Gene Goforth, who inspired him to take up the fiddle as well as the banjo. Goforth was “a big man around St. Louis,” but it was Flatt & Scruggs’ fiddle player, Benny Martin, who had the biggest impact on the Hartford fiddle style: Martin combined his double stops and lonesome bluesy attitude with an extroverted showmanship; in 1985, Hartford described him as “the strongest influence on me musically, along with Earl Scruggs.”

By the time he was 17, Hartford had joined a band called the Missouri Ridge Runners and wound up playing regularly on the radio. He also played around St. Louis with Doug and Rodney Dillard, whose contributions to the development of bluegrass would one day rival his own. Even though Hartford was starting to make a go of it as a musician, he hadn’t given up his riverboat dreams; by now he was a card-carrying deckhand. Benny Martin, Bill Monroe and Flatt & Scruggs were his musical icons, while men like Jimmy Swift, Capt. Fred Way, C.W. Stoll and Steamboat Bill, all of whom wrote for the Waterways Journal, were his guides to the ways of the river.

By 1960, Hartford had recorded a few self-pressed singles with a group called the Ozark Mountain Trio with Don Brown and Norman Ford. They did an EP called Backwoods Gospel Songs, with a John Hartford pen and ink drawing on the front cover. He made a few dollars as a banjo picker and fiddler, but also found low-paying work as a DJ, a commercial artist and a salesman. Hartford and his first wife then decided to move to Nashville. “We were just about starving to death,” I remember him saying. “I figured we could starve to death in Nashville and have a helluva lot more fun doin’ it.”

The young couple found a trailer near the Auto Auction, and the missus found a job at Glaser Brothers Music, a music publishing house that eventually signed Hartford as a songwriter. Things began picking up. He started writing prolifically, got signed to RCA and, with the “t” added to his last name, made his first album, John Hartford Looks at Life. It sold well enough that he went on to make a second, Earthwords & Music, which featured a song inspired by the film Dr. Zhivago called “Gentle on My Mind.”

As Hartford explained it to me years later, “RCA signed me because they thought I could be their Bob Dylan.” Listening to his 1967 debut album, which boasted liner notes by Johnny Cash, the wry humor makes it seem like he couldn’t make up his mind whether to be RCA’s Dylan or their Roger Miller. Each of the albums Felton Jarvis produced is a minor classic and shows how country music was absorbing lessons from the records Bob Dylan and the Beatles were making. 1968’s Housing Project, for example, included some backward-recorded banjo and other sonic hairpin turns that indicate Hartford was listening to records made outside Nashville.

That same year, Tom Smothers invited Hartford to L.A. to be a writer and cast member on the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour. John accepted, got himself a place in the San Fernando Valley and moved the wife and kid out to Sherman Oaks. By the end of 1968, he not only had a high profile thanks to the TV show, but he’d written what had become Glen Campbell’s greatest hit and had played fiddle on the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo.

By 1969, Hartford’s career was truly launched. That year he flew more miles than pilots or flight attendants were allowed per annum by law. He turned up on my TV set pretty much every Sunday. In 1969, it looked like John Hartford could do no wrong—which was a signal that, in 1970, things were about to run aground. He had gone into the studio with his road band, Iron Mountain Depot, but things just weren’t working out. “Basically, we had contracted the disease of unlimited budget,” he said. Hartford released the LP Iron Mountain Depot, named for his band, but he wasn’t really satisfied with it and felt it was too slick and over-produced.

The follow-up, Radio John, was an even more conflicted record. On one level, he’d started to shake off the excesses of the two records that preceded it, which were produced by Rick Jarrard (who had enjoyed his greatest success producing Harry Nilsson). On the other hand, it had the sound of a guy who had reached the end of a particular road and wasn’t sure if he should press forward or turn around and head back in the direction he came from.

RCA decided not to release Radio John in the U.S., but it’s unlikely that its release would have changed Hartford’s eventual path one iota, even though it contained songs that eventually became Hartford staples, like “Waugh Paugh,” “Skippin’ in the Mississippi Dew,” and the gorgeous, poignant “In Tall Buildings.” Colin Cameron, who played bass in Iron Mountain Depot and still plays great bass in what’s left of L.A.’s country-roots circuit, remembers that, towards the end, it just wasn’t fun anymore, and he wasn’t surprised when he was given his walking papers. Besides, he had an inkling that Hartford was working on a new musical direction. “There had been a session I was on with John, Vassar Clements, Norman Blake and I think one of the Dillards, and you could just kinda tell….”

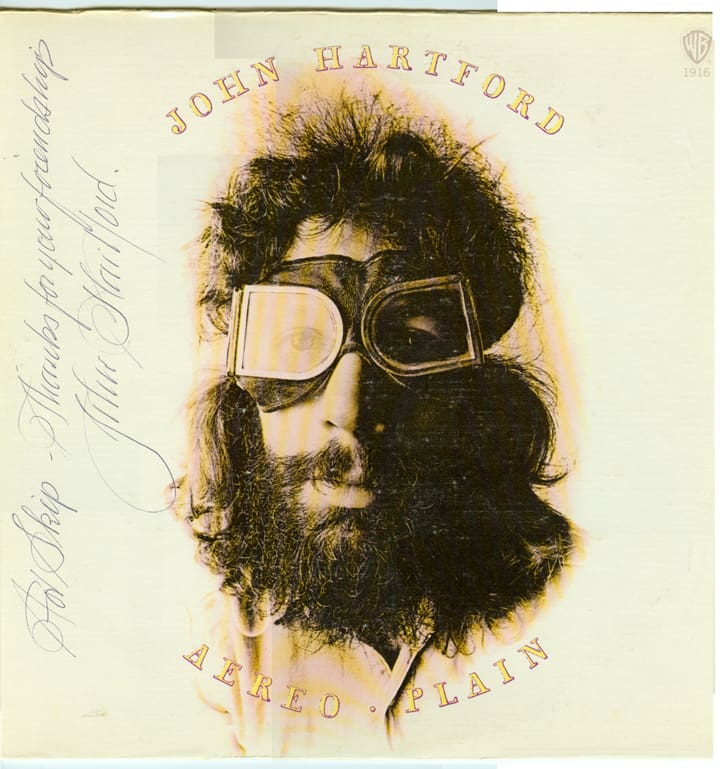

The author’s signed copy of ‘Aereo-Plane’ featuring John Hartford’s trademark penmanship.

On August 23, 1969, John Hartford had appeared on The Johnny Cash Show to sing “I’ve Heard That Tearstained Monologue You Do There by the Door Before You Go” from his self-titled 1969 RCA album and, although he didn’t know it at the time, he had discovered his new musical direction. That night he and Cash fronted a band that included Norman Blake and Vassar Clements for a medley of Bill Monroe hits to honor Big Mon’s 30th anniversary as a member of the Grand Ole Opry.

Ken Kragen, Hartford’s manager at the time, recalls the backstage scene: “The first time John played with Vassar and Norman together was on The Johnny Cash Show. Chet Atkins was the other guest. I’ll never forget it, because John started practicing in his dressing room and pretty soon—just by his magnetism—he’d drawn everyone into the hallway just to jam, and finally the stage manager put a stop to it when Pig Robbins tried to push the piano into the hallway to join in.”

In 1970, with his career at RCA over, Hartford headed to Nashville to pursue his new vision, which resulted in the 1971 release of Aereo-Plain on his new label, Warner Bros. “I’d jammed with Vassar Clements a couple of times, and he was always asking me when we’d get together and really do something,” he told me. “I put it off because I didn’t have the rhythm section that could really support him just right.” Hartford joined with guitarist Norman Blake, Dobro player Tut Taylor, bassist Randy Scruggs and, making his debut as a record producer, David Bromberg to come up with the right support.

To people who came to bluegrass via the Folk Scare of the 1960s, Aereo-Plain was one of the records that defined a generation’s approach to playing bluegrass. Aereo-Plain, along with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s Will the Circle Be Unbroken and the self-titled debut of Old and in the Way, took the classic sounds of Bill Monroe, Flatt & Scruggs and the Stanley Brothers and updated them in surprising new ways.

Aereo-Plain changed my life. For me, this record is Ground Zero. First off, it alerted me to the world beyond the South Philly/Jersey one I knew. Since I hated the world I knew, this was an important thing, sort of like a finger pointing down from the heavens and telling me, “Don’t worry: There is a life beyond Passyunk Avenue and Princeton Road.” John Hartford was singing about grown-up stuff, but it wasn’t boring grown-up stuff. He knew the river, bluegrass music, Nashville, first love and how to ask, “Hey babe, you wanna boogie?” with such joy and authority.

I was only 10 when I first heard this album, but I was not a dumb 10-year-old. It was the grill-hot bicentennial summer, and Philadelphia was an oven filled with tourists. My grandmother’s apartment was pretty far south of where everyone was checking out the important early sites of our democracy, which tended to be between Race and Locust, from the riverfront to about Seventh Street. I had a lot of time to myself and I listened to a tape of this album on the little tape recorder that I got by selling Burpee seeds for the Cub Scouts. That tape got a lot of play, and I have kept with me every sound and syllable.

The level of interaction in that band was off the hook. You could never tell who was soloing. They played together, as a whole unit. John was and is my hero of all heroes, but Vassar took me out: the freedom in his fiddle playing, the way it wrapped itself around everything like a big ribbon and grounded the music even as it seemed to defy gravity. These guys threw down like WWF champs and they didn’t even break a sweat. It was my first exposure to “the great ones” who make it look easy.

Hartford once let me know he had an agenda for Aereo-Plain: “I wanted to take what the band was doing and make it so that it could be understood by Northern people. Yankee people.” As I’ve matured, I’ve realized how deep and amazing the album really is, and Steam Powered Aereo-Takes, a disc of alternates, outtakes and unused cuts, only reinforces that. Mad huge props go to producer David Bromberg. Everything that band did was amazing—originals and bluegrass standards—and Bromberg was stuck with the unenviable task of knowing what to leave off. He really built the record around Hartford’s songwriting, with other elements (the traditional fiddle tune “Leather Britches,” Alfred Brumley’s gospel standard “Turn Your Radio On”) adding a layer of nuance.

Bromberg’s other challenge was working with Hartford’s non-verbal methodology in the studio. In fact, the whole Aereo-Plain Band approach was non-verbal. “First off, only one guy in the band had to know a song all the way through in order for it to be allowed into the repertoire,” Hartford said. “Secondly, nobody was allowed to discuss any of the arrangements except to say what key the song was in, in case you needed to move a capo or something. The arrangements were largely a matter of conscience.” And in the studio, nobody was allowed to hear playbacks, including Hartford. Rules are rules. “We went in, played it, and I told David to put it together then call me when it’s done.”

Sadly, Warner Bros. didn’t know what they had. “Warner Bros. just kinda laid down on the job behind that record,” Hartford told me. “And then I did Morning Bugle, and they didn’t get behind that one either. So I just got kinda mad at records for a while there. I said, ‘To hell with it,’ and just figured that people making their own recordings at the shows would be my records.” The next four years would be a bootleg goldmine: mostly solo shows, duo shows with Norman Blake and band shows where he took the stage with the New Grass Revival. (NGR mandolinist Sam Bush is truly one of the best musical allies John ever had.)

In 1976, Hartford finally released a new album, the solo Mark Twang, on Flying Fish. It won a Grammy for best traditional folk album. For years after, he was one of Flying Fish’s staple acts, making a series of albums during the next dozen years. Around 1980, he was diagnosed with cancer, although he didn’t make this knowledge at all public until about 1995.

Cut to Nashville, March 2006: I’m sitting in the SoBro Grill in the Country Music Hall of Fame with Roland White, and we’re talking about Bill Monroe and how Bill and John got to be great pals in what turned out to be the twilight years of each. Although Monroe was nearly 28 years Hartford’s senior, his passing in 1996 only predated John’s death by lymphoma by about five years. Roland White knew both men well. I’ve long been an obsessive Bill Monroe armchair psychiatrist, and White was a Blue Grass Boy for a time. I asked him when he heard that John had been diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. “Actually,” White recalled, “a few of us” (some of the guys he’d known forever like me or Rodney [Dillard] or Sam Bush) “we knew pretty early on. He told us and he trusted us to keep it under our hats.”

The first time I saw John Hartford in the flesh was in February of 1988 at the Painted Bride Arts Center in Philadelphia. It was a solo show, and he was beyond beyond, tap dancing, singing and playing the snot out of fiddle, banjo and guitar. He was so incredibly robust and thin as a whip. He reminded me of a piece of lamp cord with the wire exposed; the sparks were just coming off him. You couldn’t look away from him. He had a personal magic that I’ve seen very few times: where a guy looks taller and completely energized. Joe Strummer had it. It’s a no-holds-barred-enthusiasm thing.

It was an amazing show, mostly the greatest hits, but delivered with the enthusiasm of a starving man ripping into a plate of mashed potatoes. His improvising, especially on fiddle, was like a geyser: ideas exploded out of him. Like Sonny Rollins, except that Hartford’s overt joy and knack for never repeating himself made me think Cannonball Adderley. I got to meet John after the show and told him what he meant to me and how long and well I loved his music. “We’ll have to play together sometime,” he said. I walked out into the cold Philly winter night so warmed by the thought that I didn’t notice the crappy weather.

I got in touch with him again in 1995, when I had retired from playing music and was doing a bit of writing to cover the rent. I got an assignment to write about John Hartford and called him up. We spoke for two hours about everything from steamboats to hunting to banjos to shoes. His mind was incredibly agile, and I loved the way he expressed himself. It reminded me of the Big Daddy character in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. “My choice of instrument has of late been loafers,” he said. “You get a better backbeat.”

He had obviously staked out his character and perfected it. The hippie eclectic that was the Hartford of Mark Twang had been replaced by a sort of Southern riverboat intellectual historian who would occasionally revert to an earlier self and praise the Beatles. But he referred most often to fiddle players known almost exclusively to historians of competition fiddling, especially a guy named Ed Haley, to whose music Hartford devoted much of his last decade. Hartford compared Haley to Buddy Bolden, the mythic New Orleans cornetist. He also spoke at length about Capt. Fred Way, the definitive riverboat historian and an idol since boyhood.

Hartford’s life on the river had peaked as well. He was now a full-fledged unlimited tonnage licensed operator and a pilot on the General Jackson, an excursion boat docked at Opryland. Boat pilots have specialized knowledge that is not to be taken lightly. The written test (part of your qualification is on-the-job steering and navigating) is to draw a map of the 40 or so miles of river on which you’ll be working. You have to include the location and dimensions of bridges, locks and dams, the location of navigation lights and so forth. From memory.

I realized I was catching a brilliant and prolific man in the last decade of his life, and we struck up an ongoing phone friendship. Looking back, I get the feeling he knew the meter was running out because he always made it a point to dispense wisdom. John described himself to me as “a frustrated drugstore librarian of nonfiction books,” but he was, in truth, a tireless researcher. Much of his last energy was spent writing a tome-sized biography of Haley. Hartford was a recognized authority on old fiddle tunes, on bluegrass in general and on steamboat history. His knowledge of how music of all kinds and river travel influenced each other was staggering, and his memory for sources no less impressive.

After that first phone call, we were on a bill together at the Tin Angel in Philadelphia, and I didn’t recognize him at first. The cancer and the chemo seemed to have shrunk him. He wore red horn-rimmed glasses and sound-checked quickly before retiring to his bus to rest before the first of two shows we played that night. Even in his depleted condition, he slayed the audience at both shows. Profound musical ideas poured from his fiddle, although the banjo had definitely been relegated to second-class citizenship.

The last phase of John Hartford’s life was a period of re-evaluation. His marriage to Marie Barrett was his third and final, and he made it a point to become more involved in the lives of the children (a son and a daughter) from his first marriage. His son, Jamie, is a musician and songwriter active in Nashville and is enough of a player to have recently replaced Albert Lee in the Everly Brothers’ touring band.

The last phase of John Hartford’s life was a period of re-evaluation. His marriage to Marie Barrett was his third and final, and he made it a point to become more involved in the lives of the children (a son and a daughter) from his first marriage. His son, Jamie, is a musician and songwriter active in Nashville and is enough of a player to have recently replaced Albert Lee in the Everly Brothers’ touring band.

Jamie Hartford was still fairly green when he first recorded and toured with his father—the first Hartford and Hartford bootleg I have in my comprehensive, 200-strong collection is from early 1989—but he still held his own. He still remembers what his father said to him the first time they played together onstage: “Dad told me right before the first show, ‘This is a good act. Don’t ruin its reputation.’” No pressure.

Jamie Hartford is what his father would have called an “old boy,” a term he used the way South Philly Mafiosi once used the term “my very, very good friend.” The people to whom John referred to as old boys were sons of the South, pickers whose instrumental prowess was, well, frightening: Benny Martin, Bill Monroe, Earl Scruggs and Sam Bush were all old boys. Jamie’s low voice is similar to his father’s, but a little gruffer. The gruffness is actually a tad misleading; it’s that laconic Southern thing (Northerners, think Mose Allison) that Southerners expect from each other but that Northerners don’t know how to take.

Jamie Hartford was raised in a hunting and fishing household by a stepfather who had been to Vietnam, and he knows way more about guns than Ann Coulter, which is to say he has brains enough not to hunt big game with an AK-47. He has the same kind of analytical mind, authoritative attitude and common sense that his father had. Jamie’s examination of his father’s later life doesn’t miss any spots. John may have been a “what you see is what you get” kind of guy, but what you saw was complex. “When his illness had to be factored into every aspect of how he lived his life, he made up his mind to deal with the things that were the most important,” Jamie says. “Certain songs he wouldn’t do anymore because they referred to illegal substances, and he wanted to be able to play for your whole family.” I laughed when he told me that.

When his father and I first spoke, I was nearing three years of sobriety, and John said, “You know, I keep wondering if I should learn how to drink, but I just don’t seem to be any good at it.” Jamie laughed when I told him this. He attributes it to his father’s relationships with guys like Earl Scruggs, Jimmy Martin and Benny Martin, all “old boys” with whom he’d go hunting. “Those guys, man, he looked up to them,” Jamie says. “Benny was his hero, and they’d talk every day, pretty much. And Earl, well, Earl’s Earl. Dad never felt like he was as good as they were. There were people, especially on the West Coast, who got Dad’s thing and held him in similar regard to Benny or Earl, but he’d never claim it himself.

“People saw Dad as a bandleader, but he loved just being in the band sometimes. One night, Earl got called to play some thing where the president was gonna give him a Medal of Some Kind of Arts, and he brought Dad along to play guitar, and Dad put on his fingerpicks and played that ‘whip-chicka’ Lester Flatt thing exactly. And he loved gettin’ the chance to do it. He loved playing banjo like Earl behind Benny. That was his roots.”

Jamie Hartford and I were born about five months apart, and (because of his father’s touring schedule) he learned about his father in much the same way I did: from records. Jamie and John got to know each other later in life, but it was still strange to be able to tell Jamie things about his father he didn’t know. Like when I mentioned that the cartoon show South Park really offended John: “That’d make sense,” Jamie said. “He stopped singing ‘Granny Woncha Smoke Some’ and all that so kids wouldn’t ask what the lyrics meant. . . . He really told you that?”

In the course of his Ed Haley phase, John had really changed his intonation on fiddle. He’d finish phrases sharp and never use open strings. I asked Jamie whether those ideas had come from Haley.

“Actually, you left out one of Dad’s most biggest influences,” he replied. “John McLaughlin.” That almost gave me whiplash. “We used to listen to all that Mahavishnu stuff, and I think that’s where Dad learned how to play some of that ‘out of the chord’ stuff and those long lines. And some of those things he cut with [Indian violinist Ravi] Shankar got him thinking about the notes between the cracks.

“Ed Haley did the same thing, where he’d play sharp just to make his playing stand out a little from what the other fiddlers would play at the competitions. So I think it’s fair to say that what opened up Dad to the notes in the cracks before he ever heard Ed Haley was John McLaughlin because that’s where he started thinking that way.”

For John Hartford, the riverboat and the tour bus were just manifestations of his restless mind. At his most prolific, he put in more miles on the road than just about any artist this side of James Brown and he collected tapes (and later DATs) of pretty much every show he ever played. Also, it would seem from the release of Steam Powered Aereo-Takes that he saved tapes of his sessions as well and, according to Jamie, even tapes of himself practicing. “We’d get done with a gig, and I’d get on the bus to get some sleep,” Jamie says. “And I’d hear the metronome start beepin’, then the fiddle.”

Last year, there was a new Jamie Hartford CD, Part of Your History: The Songs of John Hartford, which put the younger Hartford in the company of some of the old man’s musical allies (Vassar Clements, Sam Bush, Norman Blake, etc.) and friends (Béla Fleck, Tim O’Brien, Emmylou Harris and Nanci Griffith among others). The fantastic performances were true to the spirit of the songs, but the songs were the real stars. At the end of the sessions, John Hartford’s personal Deering banjos were handed over to Béla Fleck. As far as I know, the strings and the setup were unchanged from the last John Hartford gig, and I’ve heard that Fleck intends to keep them that way.

In the back of my mind, I can still hear John Hartford answering my question that night at the Tin Angel when we played together, about how he played two sets’ worth of solos without ever repeating himself.

“I just try to get my hands and my feet and my mouth to do what I hear in my head,” he said, “even though I know it’s just gonna come out how it’s gonna come out, and there ain’t a damn thing I can do about it.”

[Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared as the cover story in the Fretboard Journal #4, Winter 2006. Illustration by Brad Howe.]