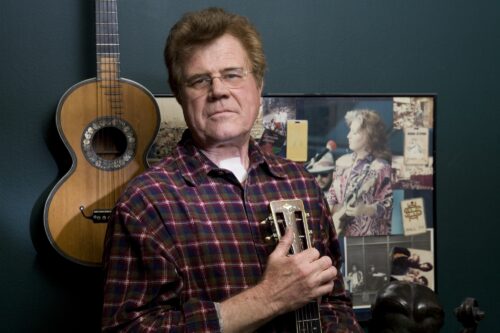

“When I grow up, I want to be Fred Walecki.” -Emmylou Harris

Talk about a star-studded night. On August 8, 2000, the cream of a Los Angeles rock generation joined together for a benefit concert at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. Billed as “Friends of Fred Walecki: A Gathering of the Clan,” the lineup featured Jackson Browne, Linda Ronstadt, Emmylou Harris, Graham Nash, Bonnie Raitt, David Crosby, Don Henley, Ry Cooder, Warren Zevon, Chris Hillman, Bernie Leadon, Spinal Tap, Albert Lee and many more.

The concert, organized by Leadon and producer Glyn Johns, was noted for its generosity of spirit–egos and past band enmities checked at the door–and proved to be an inspired evening full of soaring harmonies and onstage surprises, including a historic reunion of the three surviving Byrds. Roger McGuinn, with his iconic blonde Rickenbacker 12-string, joined Crosby and Hillman to sing “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “Turn, Turn, Turn”–the same way they did it 30 years ago. (A second show was added after the first sold out, and that show sold out as well.)

Many ticket buyers were drawn by the marquee names, but had no idea who Fred Walecki was–or why such a stellar lineup had assembled on his behalf. But serious guitar players who pass through Los Angeles know Fred Walecki.

The Walecki family has owned Westwood Music for half a century. The spacious, comfortable shop in West Los Angeles is a favorite haven for pro musicians who are drawn to Fred Walecki’s infectious brio–and his adventurous taste in instruments from the latest and most innovative builders. “Fred dealt in boutique gear long before it was called boutique,” says his friend Geoff Cline. “He was always the first to get the hand-built stuff you’d never heard of: amps from Dumble, Victoria and Carr; acoustics by Mark Whitebook, David Russell Young, Bryan Galloup, Roy McAlister, [Matt] McPherson; electrics by Chris Larsen’s Girl Brand, Versoul, Ken Parker, John Bolin. He takes chances on new builders, often giving them the encouragement–and orders–they need to build more instruments. Fred is genuinely interested in how to make musicians’ lives better.”

Emmylou Harris recalls how she found the guitar that has become identified with her: “In the mid-1970s, I got a call from my friend Fred Walecki in L.A., and he said, ‘I’ve got a guitar in here that you really need to play. It used to belong to Joe Walsh.’ It was a sunburst Gibson J-200 that had a factory pickup in it. It was just the most beautiful thing I had ever seen, and I loved the sound of it.”

In 1992, Walecki heard from Jackson Browne (who had heard from John Jorgenson) about a promising new Vox AC-30-inspired amplifier called Matchless being made by a couple of local guys. “Fred called us and bought two amps over the phone–and gave us a deposit for two more,” says Mark Sampson, who built the original series of Matchless amps with Rick Perotta. “He was our first dealer. We were elated at his involvement because he has a high-end clientele–exactly the musicians we hoped to reach.”

“He always had the best amplifier,” says Ned Doheny, a friend and noted guitarist whose father bought him his first guitar–from Walecki’s father, Hermann–when Ned was in the third grade. “Fred would devote hours to showing you the intricacies of some new amp design and explain why it was so much better than the last great amp you bought from him.”

David Crosby gets most of his guitars from Westwood Music. “Fred is my guitar guru,” says Crosby. “He really knowsguitars. It’s very dangerous to go into Fred’s shop.” Indeed, there is Crosby’s 1928 Martin 000-45, secured in its original case in a corner of the store as Crosby waffles over whether to sell or hold. It is a very dangerous guitar.

But Fred Walecki is more than a purveyor of fine instruments. His true business is people. For more than four decades, he has been at the epicenter of a vibrant West Coast music scene, connecting players with instruments–and with each other. “Fred’s talent is with friendships,” says Mark Bookin, Walecki’s longtime partner in the store and one of his best friends. “The retail business is not so interesting to him. His real satisfaction is in relationships. He makes you feel special, and it’s not just to sell you. He really likes people. Taking a chance on new gear is really taking a chance on people.”

The store serves as a community center for musicians, roadies and guitar techs between gigs. “It’s more of a salon than a typical guitar store,” says Bernie Leadon, who has known Walecki since they were both teenagers. “Fred’s store has always been one of the places I could go and run into my peers, meet a producer, renew acquaintances. My friends and I would go there three or four times a week just to check in. It was like a daytime club.”

Walecki has catered to his creative and often idiosyncratic clientele, ready to provide emergency support to touring bands by sending out replacement guitar parts, amps and speakers on a frantic road manager’s call. He’s been a therapist for bands with fragile egos and personnel problems. He has helped people get sober. All of it makes good business sense, certainly–solving problems and smoothing the bumps for special customers–but there’s something else involved, which might be attributable to Walecki’s uncommon decency.

His friends praise his loyalty, his discretion and the moral manner in which he conducts himself. “He’s a man who loves people and enjoys being in a position to help them,” says Chris Hillman. Ned Doheny adds, “Fred is a warm soul with a great heart.” Mark Bookin affectionately calls him “Saint Frederick of Westwood.”

The front room of Westwood Music features a full range of Martin, Gibson, Collings, Santa Cruz and Breedlove acoustics displayed on wall pegs, with racks of 12-strings and classical models clustered around the floor. There are thick leather couches to encourage sittin’ and pickin.’ Joe McNamara, a rep for Martin, sits on the couch and recalls his first trip to the store 11 years ago.

“When I was initially assigned to the West Coast territory, the first stop I made was to Westwood Music,” says McNamara, “out of respect for Fred, the legend, as well as Fred, the store owner. He has been instrumental in so many great careers.” Chris Martin IV, the current head of his family’s venerable company, spent six months of his youth working at Westwood Music in the early 1970s.

“I was about to go to college and study marine biology when I first became excited about the guitar business,” Martin relates. “Fred was visiting my father in Nazareth, [Pennsylvania,] and suggested that I come out to UCLA to study and work part-time in his store to learn the retail end of the business. That’s what I did. Fred put me together with John Carruthers in the back learning about repairs, and then I’d go out front to deal with customers. And what I learned was that the people out front knew a lot more about my family’s products than I did.”

Thanks to his time at Westwood, Martin also gained an appreciation of the personal level of service that can make a difference in the sale of a high-end guitar. “Fred’s enthusiasm is contagious,” he says. “I don’t know if he’s a great guitarist, but he has a couple of licks that make a guitar sound really good–that a customer will hear and go, ‘Oh yeah, that’s what I want to hear!’–and he’s sold a lot of guitars off that lick.”

Across the room by the register are glass-cased counters containing a collection of the finest in pedals and stomp boxes. Small jewelry boxes feature sets of custom-designed bridge pins made of fossilized mammoth, buffalo horn and ivory. Walecki was one of the first dealers to carry these pins, and he loves nothing more than to demonstrate the dramatic difference in string definition and clarity gained by substituting the denser horn and ivory pins for the standard plastic pins on an acoustic guitar. Hanging on a wall above the glass cases is a grouping of classic electric guitars that would send a jolt through the most jaded vintage freak: a well-loved ‘55 Strat, a ‘65 Gibson 335, a ‘68 Tele bass, a ‘55 Goldtop, a ‘50s Les Paul Special and Junior, both in matching TV yellow. All of these creampuffs are on consignment, and, combined, they will cost about as much as your house.

The back room showcases an eclectic assortment of amps and electric guitars, most of which won’t be found in the local megastore chain. There are a few familiar ‘60s-era Vox, Gibson and Fender amps, but the floor is dominated by more contemporary models. A few vintage Epiphone and Gibson electric archtops hang on the wall among the latest creations by boutique upstarts. The walls not covered by guitars show off gold records presented to the store from Little Feat, Bonnie Raitt, the Eagles, Poco and Heart. A raised stage area at the far end of the room, originally intended as a performance space, is instead filled with bass amps. (One can only imagine the range of talent Walecki might have lured onto this stage had he followed through on this entrepreneurial idea.)

Up a flight of narrow stairs is the repair workshop, a cramped warren of drills, band saws and workbenches flanked by rows of guitars in cases waiting for attention. On the workbench, its neck resting on a gray bag of buckshot, is a wonderful 1930s Stromberg Master 300 archtop that Walecki is restoring for the widow of a local club musician.

“This is what I enjoy most about owning a music store,” he says, “working on an instrument with a history, a slice of someone’s life.” He dips a small piece of 2000-grit wet-dry sandpaper into a plastic tub of water and rubs the Stromberg’s neck and between the frets to remove a brownish goo–the result of years of accumulated cigarette smoke. “This makes Kris Kristofferson’s guitar look like amateur night in Dixie,” he laughs. Here at the bench, surrounded by tools, wood clamps and bottles of stains, solvents, varnish and lacquer, is where Fred Walecki is at his most relaxed and focused, freed from the hubbub of commerce, in touch with the skills handed down through his family.

His father, Hermann, came from Polish ancestry, was born in England and grew up in Canada. “My dad studied violin growing up on a small farm in Saskatoon, [Saskatchewan,]” Walecki recalls. The family business was making cabinets. “Dad apprenticed with his father and learned about wood finishes, gold leafing and French polishing. They built a lot of church furniture. You can still travel through the churches of that area and see altars and pews they made.”

As a young man, Hermann moved to Chicago and went to work selling instruments for Lyon & Healy. As a teenager, he had sent away for the Lyon & Healy catalogs, which featured beautiful color plates of rare Stradivarius and Guarneri violins, violas and cellos. With his photographic memory, Hermann memorized the history and word-for-word descriptions of every instrument. He impressed the Lyon & Healy hierarchy by demonstrating–in six European languages–that he knew their inventory better than they did, which gained him a position in the rare-violin department.

Hermann moved to Los Angeles in 1936 and established a branch of Lyon & Healy on Wilshire Boulevard. “My dad was an Old World intellectual,” says Walecki. “He knew many languages. He could engage people in a social way. Many string players from the movie-studio orchestras came to him. My dad would talk philosophy and poetry with the musicians while he repaired their violins and re-haired their bows.” A regular customer–and future golf partner–was Harpo Marx.

In 1947, Hermann Walecki opened his own store at 2085 Westwood Blvd. He stocked (and rented to students) only high-end instruments, and his store became known for quality. The one instrument he refused to carry was the steel-string guitar. “He didn’t want that element in the store,” his son says. “He never understood modern music, nor did he care to. He was consumed by classical music.”

Fred Walecki was born in 1946, and he grew up in a house filled with music, poetry and culture. His sister, Christine, was a cello prodigy who played with the National Symphony when she was 12. His older brother, Ronnie, had a mind for math and engineering.

“My parents were bohemian in that they had no concept of what the Joneses next door were doing,” remembers Walecki. “They were artists. My mother played and taught violin and cello. She gave lessons to 40 students a week. She also conducted live theater orchestras in an era when the conductors were exclusively male. We didn’t own a television until I was 8. Our living room was stacked with these giant looming harps that wouldn’t fit into the store. I’d walk through the dark house at night and bump into these harps, which was spooky for a little kid.

“My parents hosted cultural and musical evenings. There were always great musicians around, string quartets and trios. Dad was part of an informal group of local intellectuals called the Cliff Dwellers. There was a Shakespearean actor named Richard Hale and the [Los Angeles] Herald Examiner music critic Raoul Grippenwald. There was always something interesting happening in the house.”

Walecki’s first instrument was the trumpet, but he soon grew passionate about the guitar and studied flamenco and classical technique. He worked at the store after elementary school, sweeping the workshop and giving lessons. “When I was 12 years old, my dad took me up to the repair shop and taught me to use his tools,” he recalls of his first attempts at woodworking. “He started me off doing setups of the inexpensive nylon-stringed rental guitars, oiling the pegs and measuring string height. Then he showed me how to fix cracks. He was patient and supportive, and, as long as the instrument was a junker, he let me make my own mistakes because he wanted me to figure out how to do it the way I thought it should be done. And then he’d suggest how the repair should really be done. I learned about these instruments through my father’s eyes.”

There are two large safes in the store office dating from Hermann’s era. One contains a library of musty hardcover reference books and portfolios from a past century, many written in German and Italian. The volumes feature color plates of rare violins, violas and cellos and long exhaustive descriptions of their identifying characteristics. There are also detailed guides on the restoration of classical instruments. The interior of the second safe is sectioned into small cubby holes, each holding an old violin from Hermann’s collection.

Fred Walecki removes a violin from the safe and looks it over, pointing out the good and bad repairs. (His father would refer to the lesser work of another craftsman as “shoemaker repairs”–or, more colorfully, petso de merda, or piece of shit.) “When Dad was re-hairing a violin bow, he’d have me cut off the excess hair with a knife,” he recalls. “We bought horsehair by the bundle. I’d wet-comb the hair until it was nice and flat. Dad gave me a chance to have my own opinion on how much hair to use.

“After that, we started getting into finishes, varnishes, French polishing, and this was where my family history served me well. We had custom-made polishes handed down from my grandfather’s days studying with the royal cabinetmakers in England. At one time, Dad consulted with Dow Chemical to identify what type of varnish Stradivarius had used on his violins. It was found that what was most possibly a drugstore formula at that time was not only used by Strad, but also the other famous Cremonese makers.”

In 1952, the music store relocated to a larger space at 1611 Westwood Blvd. At that time, there was a vogue for after-dinner window shopping along the boulevard, and the shops stayed open on Friday nights. Window dressings were considered all-important. There was a competition among the stores to come up with the most imaginative window scene. “We would display a real Stradivarius in the window,” Walecki says. “Can you imagine doing that today?”

Hermann had become internationally known as a connoisseur of rare violins. He traveled in a world of collectors and celebrity musicians and was involved in selling and brokering some of the century’s most important instruments, including the Lord Nelson Strad, the Markevitch Strad, the Red Diamond Strad, the Colossus Strad and the Mendelssohn Strad.

“Dad sold a Strad to Henry Ford, which is now in the Ford Museum in Michigan,” Walecki remembers. “We had this 1949 Packard Clipper. In 1954, we drove it up to Vancouver Island to sell the Lord Nelson Strad to Horace Plimley, who was the sole importer in Canada for Austin-Healey, MG, Morgan and Jaguar. We traveled at night; it was a full moon. I had fallen asleep on his lap. I woke up, and Dad saw that I was awake and started quoting from the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. I remember one of the lines was, Awake my little ones and fill the cup before life’s liquor in its cup be dry, and I just remember staring past the steering wheel, looking at the stars, and he was driving … with the swamp cooler hanging out the window. It was a dreamy life for a kid.”

Fred Walecki came of age learning the tricks of the retail trade. “I used to bring my little Scottie dog to the store,” he says. “Dogs respond to certain musical timbres. My dog would howl every time a customer hit certain notes on a violin. So there was a signal that my dad would give me, and I’d have to take the dog out for a walk in the alley so Dad could make the sale.”

Working behind the counter offered the younger Walecki an early education in ethics and values. “I sold a customer a set of expensive strings for his cheap guitar,” he recalls. “After he walked out, I proudly told my dad about the sale. He observed that the customer looked like he didn’t have much money, and did he really need the best strings, and would they really make a difference in how his guitar sounded? Then he gave me a set of cheaper strings and told me to go down to the bus stop and make an exchange with the customer and refund him the difference. It gave me some insight into how my father viewed the world.”

The surf craze swept into Southern California in the late ‘50s. Dick Dale was playing at the Rendezvous Ballroom. Meanwhile, Fred Walecki was going to University High with his friends Steve Cahn (Sammy’s son, who changed the spelling of his last name to Khan and became a jazz-guitar star), Jeff Bridges and Steve Raitt–Bonnie’s brother. “Dad was spending more time in Europe buying and selling violins,” recalls Walecki. “I started to take over ordering at the store.”

Walecki again approached his father to carry steel-stringed guitars. When Hermann Walecki balked, his son offered to pay rent to take a small room at the store and create a side business in steel-strings. Hermann finally relented. Fred called on Hilmer “Tiny” Timbrell, a former studio guitarist and player on a number of Elvis’ movie soundtracks, to help him secure a Gibson franchise for the store. He ordered an ES-175 and J-45. (“I hoped they wouldn’t both arrive at the same time because I was planning to pay for one with the sale of the other.”) The guitars sold quickly. Fred added a 000-28, D-18 and D-28 from the Martin line. They also sold. His father was pleased at the success, but still didn’t want to know about “that element.”

That element could no longer be ignored upon the opening of Ledbetters next door to Westwood Music in 1962. The club was the brainchild of Randy Sparks, founder of the New Christy Minstrels and a folk impresario. Sparks booked a wide range of folk and bluegrass musicians, including Mike Nesmith, Larry Murray (Hearts and Flowers), John Denver and the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers (a San Diego-based bluegrass outfit that featured Chris Hillman and Bernie Leadon). Soon, the Ledbetters musicians were frequenting Westwood Music looking for strings, capos and someone to repair their guitars. Hillman, who played mandolin with the Barkers, bought his strings from Walecki’s father.

“I didn’t meet Fred until Bernie Leadon introduced us,” Hillman recalls. Leadon remembers his first time at Westwood Music. “I saw a National Tricone resonator in the window and went inside. I was struck by the ambience; there were all these antique violins and cellos on the walls. It was not just another guitar store. Fred was behind the counter. He was my age, 16, and dressed very preppy. I asked about the National. Fred told me it was $400, which I couldn’t afford. But he was very personable, and I remembered him the next time I went in.”

Leadon introduced Walecki to his friends and bandmates, including the Flying Burrito Brothers. Years later, he brought in members of his new band, the Eagles. Mark Bookin was in a Randy Sparks-sponsored group called the Back Porch Majority. Walecki came to see the group perform next door. He and Bookin got to be close friends, and when Bookin’s guitar was stolen from his car, he bought a Martin from Walecki on time. “Fred is famous for his creative deals,” says Bookin. “If you fall in love with a guitar you’re playing in the store, Fred–if he knows you–will urge you to take it home and play it for the weekend. It’s an irresistible offer for a guitar nut, and a smart one. Fred knows that once you take it home, you’ll buy it.”

In the mid-‘60s, Hermann Walecki became ill with cancer. There was no substantial health insurance, and the family income went to medical care. Fred would take money out of the store’s register to pay nurses in cash. He fended off the vendors with the story that his father was traveling in Europe. Hermann died in 1967, and at the age of 18, Fred, then a student at Santa Monica City College, took over the store.

“How do you take your father’s place?” Walecki muses. “I was not essential to the store in any way before he got sick. Dad wasn’t grooming me to take over. He told me I had better things to do than this.”

The store was in dire financial shape. Walecki went to the vendors and apologized for misleading them about his father’s illness. The vendors stuck with him. “I worked long hours, late nights, behind in my payments, terrified of losing everything my father had built,” Walecki recalls. “I was in need of a major miracle.” The miracle appeared in the form of a tour bus that pulled up in front of the store. Out stepped Merle Haggard and band.

Hag was looking to buy a first-rate violin as a special gift for a friend who played fiddle music. Walecki offered an appropriately modest instrument, but Haggard wanted something “that would have no equal among fiddles.” He was trying out a Carlo Antonio Testori when Marian, Fred’s mother, walked past the violin room. “She beckoned to me,” Walecki remembers. “‘That looks like a nice instrument,’ she said with a disparaging edge. ‘It sounds like it has steel strings on it.’ I had changed the strings for Haggard, and my mother, with her discerning ear, could hear the difference. ‘He’s going to buy it,’ I whispered to her. ‘It sounds great,’ she replied, with the great relief of weight lifted off our shoulders.” Haggard purchased the Testori for $16,500 cash. “The violin had belonged to my father, so it was pure profit,” says Walecki. “It bailed us out with our loans and vendors.

“Our angel was named Merle Haggard.”

Walecki’s hard work–and his instinct for creating an atmosphere where musicians liked to gather–resulted in increased sales and awareness among the rising stars of the burgeoning Los Angeles scene. David Lindley drove in from Claremont to shop at the store. Ned Doheny came by with his singing partner, Jackson Browne. A barefoot and fetching Linda Ronstadt appeared one afternoon accompanied by her boyfriend, J.D. Souther, looking to rent a violin for her band, the Stone Poneys. Walecki felt like a voyeur of that generation, even though they were close to his age. (“I couldn’t believe how relaxed things were in terms of dress and manners,” he says.)

Bernie Leadon saw Martin guitars flying out of the store on a daily basis. He challenged Walecki to take off the coat and tie that he’d wear out of respect for his classical clientele and dress more like the rockers. “Aren’t we buying as much stuff as they are?” asked Leadon. The next day, the coat and tie were gone. Walecki gradually phased out of the classical-instrument business. Every time he sold a violin or clarinet, he replaced it with a good guitar.

“I came to realize I didn’t identify with violin people,” Walecki says. He filled the window with Martins and Gibsons. He hired the best and most personable teachers: Frank Hamilton, the leader of the Weavers, taught fingerstyle acoustic guitar; Phil Farney taught jazz guitar; Mitch Holder gave lessons in becoming a studio player; Herb Pedersen taught five-string banjo and rhythm guitar. Everyone had their specialty. Luthiers were drawn to Walecki because of his knowledge and appreciation for their craft. The repair shop employed highly skilled artisans such as Ren Ferguson, Rick Turner and John Carruthers, all of whom went on to build their own line of instruments.

Walecki never thought of Westwood Music as a creative enterprise, but he practiced a form of alchemy in the upstairs workshop, repairing and restoring instruments using solvents such as “Hermann’s Polish,” a formula created by his father. Chris Hillman remembers how Walecki rescued his prized Gibson Lloyd Loar mandolin. “It was a gift from Stephen Stills,” Hillman recalls. “It was in immaculate shape. I took it out on the road with the Burritos and accidentally hit it against a microphone and put a big scratch in it. I felt like I’d been given the Golden Chalice, and I’d dropped it.”

A downtrodden Hillman brought the mandolin to Walecki, who successfully used his circular French polishing technique on the Loar; the scratch came out. “It was like he performed a miracle healing on the instrument,” marvels Hillman.

Walecki has amassed a library’s worth of knowledge about dealing with wood. Nathaniel Kunkel, the engineer and producer of Lyle Lovett’s albums, was working at Conway Studios in Hollywood when he called Walecki, complaining of a horrible buzz in a standup bass. They couldn’t figure out where the buzz was coming from and hoped Walecki would come down to fix it. Walecki asked if there was a shower at Conway. Kunkel, puzzled, replied that there was. “Turn on the hot water, steam the room and put the bass in there to see if the buzz goes away,” Walecki suggested. It did.

Walecki also solved Joni Mitchell’s touring dilemma in the workshop. Her penchant for alternate tunings–she uses 51 separate tunings in her music–required her to bring so many guitars on the road that she had grown frustrated with touring and considered quitting the stage permanently. In the spring of 1995, Walecki told Mitchell that he was building her an electric guitar that would alleviate her tuning issues. He found an ultra-light piece of German spruce for the body and modeled the neck on a ‘62 Strat. The electronics were supplied by a Roland VG-8 processor that replicated and stored all of her tunings. The result delighted Mitchell.

Walecki then told her that he was going to have luthier Ken Parker build her a fancier version with the same electronics. “What will it look like?” she asked. “Like something out of the movie Brazil,” he replied. Mitchell loved Parker’s guitar and made it her main instrument. “The next time Ken was in Los Angeles, I casually suggested that we have lunch with one of my singer-songwriter buddies,” Walecki relates. “We drove up to this house above Sunset, and when Ken realized it was Joni’s house, he was blown away. Joni told him how much she enjoyed the guitar he’d made for her, and Ken told her how honored he was that she was playing it and how much her music meant to him, and the both of them were crying.”

Walecki married Kathy Bidart in 1991. She had grown up on a Basque ranch in northern Nevada and graduated from Stanford. When he announced to his new bride that he had purchased a plot of land on a remote knoll in Topanga Canyon to build a house, she was unfazed–the ranch she grew up on was a hundred miles from the nearest phone booth.

Their solar-powered house was completed just weeks before the big Malibu fire of ‘94. “It was my new house, and I was determined to save it,” says Walecki. “I had the help of three firemen who had mistakenly driven up to my property after getting lost in the haze of smoke and ash. We successfully battled the fire, but afterwards, I realized that my throat had been seared.”

Walecki was a longtime smoker but had quit. His brother-in-law, a doctor at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, heard the troubling rasp in Walecki’s voice and recommended tests, which indicated an aggressive form of throat cancer. He underwent an emergency laryngectomy. (“It’s a most insulting operation to the human body,” he says. “They open you up like a Pez machine.”) He spent six days in ICU recovering while news of the devastating diagnosis spread among his friends. They gathered at the hospital, hoping to offer the healing vibes. Glyn Johns contacted Bernie Leadon about doing a benefit to offset Walecki’s mounting medical expenses. Leadon called David Crosby, who called Hillman, and it snowballed into what ultimately became the “Gathering of the Clan” benefit in August of 2000.

“The first night was special for me,” Chris Hillman remembers, “because that day, Vanity Fair had scheduled a photo shoot of the three remaining Byrds at the Ambassador Hotel. Roger [McGuinn] was there with his 12-string, David [Crosby] had an acoustic and I had my mandolin. After the shoot, I casually invited Roger to the benefit soundcheck at the Santa Monica Civic. The three of us show up, totally spontaneous. We start playing “Turn, Turn, Turn,” and you could hear a pin drop. It was magical.” Later that night, the unannounced Byrds reunion set drew the largest applause of the show, but, as Hillman says, “The evening wasn’t about us; it was about Fred. To have affected so many people in such a positive manner is a testament to him.”

Around the time Walecki became ill, his friend and fellow guitar nut Nigel Sinclair took his film investment company public. With time and money on his hands, Sinclair approached Walecki and Mark Bookin about becoming an investor in the store. In 2001, Sinclair and Walecki became equal partners in the most recent iteration of Westwood Music, located at 1627 Westwood Blvd., just up the street from the original location. There was a big party to celebrate the opening, and all of the usual suspects–Browne, Raitt, Crosby and many others–showed up. Everyone had a “Fred story.”

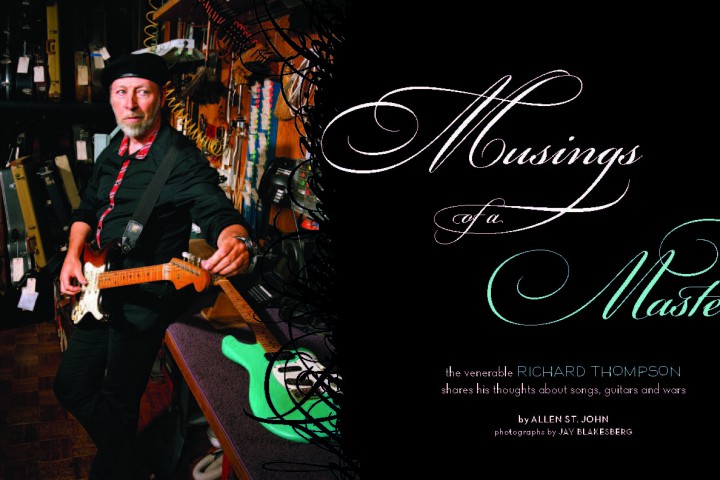

In an era of big, impersonal guitar-store franchises, eBay and the Internet, Westwood Music remains the home of the pros. Mark, Leland, Phil and the other members of the staff offer friendly, knowledgeable service, and they still have the cutting-edge gear that nobody else in town has. Richard Thompson was in recently to check out a new pedal. Joni Mitchell stopped by to play a Roland keyboard. Loudon Wainwright came through just to say hello.

Fred Walecki is behind the counter, as cheerful as ever. Though he now speaks with the aid of a handheld electrolarynx, his energy for schmoozing and storytelling is undeterred. He is still a tinkerer at heart and loves to, say, address a pickup problem on an Iranian tar or change the bridge pins on a vintage J-45 to improve the timbre and tone of the instrument. His talent and experience with guitars is matched only by his grace and good nature, and it explains why musicians and civilians alike continue to gravitate to him. And it explains why Fred Walecki is such a beloved figure in the musical community he helped cultivate.