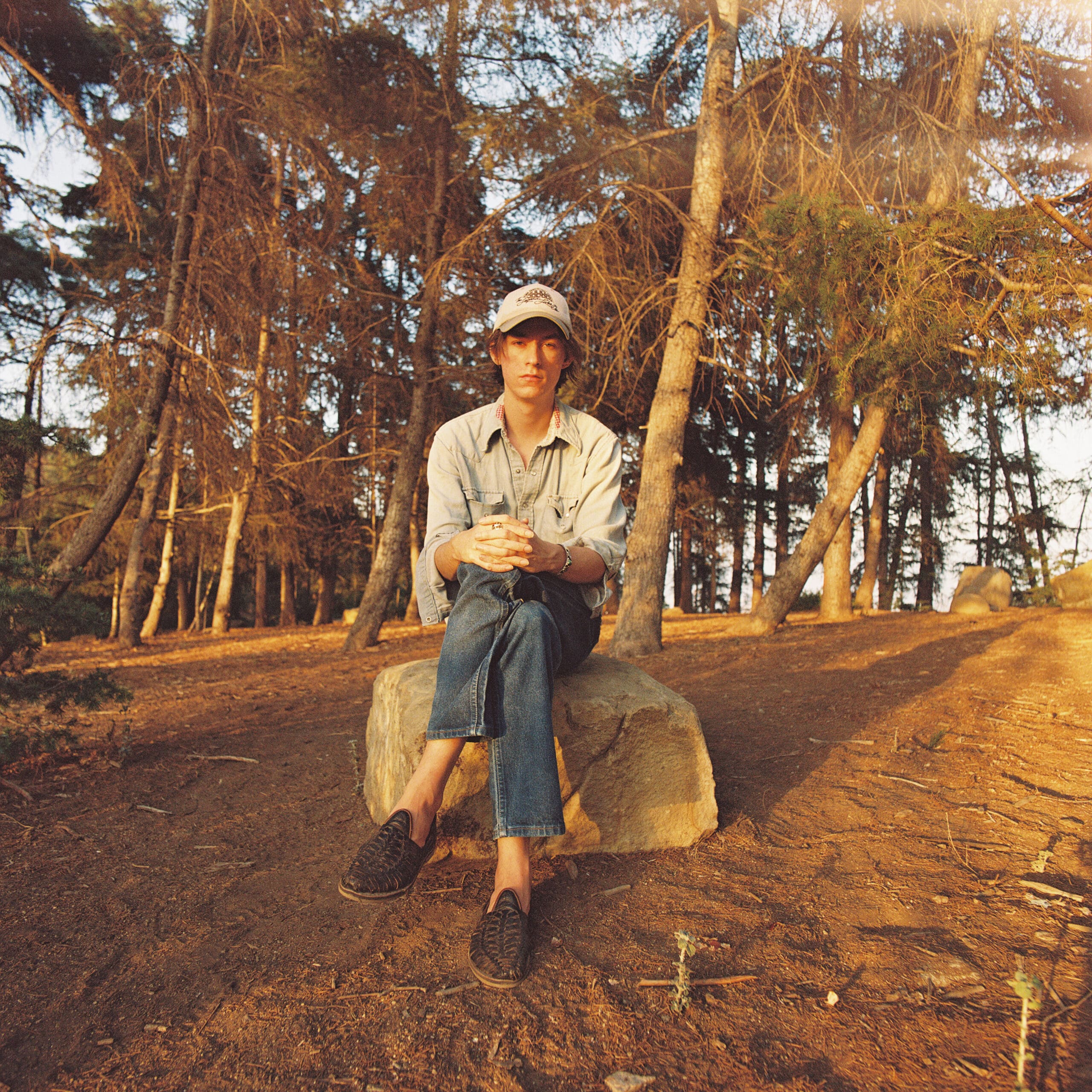

Photo by Steven Perlin

Today, contributor and FJ56 subject Cameron Knowler has released a covers EP, East of the Gilas (Lagniappe Session). In honor of his new EP, we are giving online readers an exclusive look into the pages of our print magazine by publishing Philippe Custeau’s profile of Knowler from our 56th issue. We also recently put out a live video of Cameron performing “Sunflower River Blues” on our YouTube.

Sonoran Gothic

Yuma-born, Nashville-based Guitarist Cameron Knowler

By Philippe Custeau

“Who is your favorite guitar player?” Cameron Knowler asked. It was a blustery January morning in 2022, and we were meeting for the first time. My interest had been piqued by “Guitars Have Feelings Too,” a book he’d recently released, part instructional manual and part flatpicking manifesto. I had sent him a message to inquire about his teaching schedule, and he’d promptly suggested we convene on a video conference to see if we could be a good fit.

I was initially taken aback when he appeared on screen. He looked to be in his early 20s, and so, by all measures, I’d already been playing guitar for longer than he had been aware of their existence Knowler sat upright, almost stiffly, his long thin hair battling some imperceptible wind. He came off as so unassuming and soft-spoken that the bluntness of his query also caught me off guard, and I wondered if we would be able to find any common ground there. I considered this for a moment. “Probably Robert Bowlin,” I replied, “and John Fahey.” Knowler’s eyes widened. “Robert Bowlin?” he repeated, visibly surprised. “I wasn’t expecting that.” He then added, “Never heard him and Fahey brought up together.” I told him I thought that, oddly, there were elements connecting the two. He nodded in approval. “I couldn’t agree more. I think we will be just fine.”

Photo by Micah Matthewson

Knowler laughs when I bring this up as we sit down again two years later, this time to discuss CRK, his latest collection of tunes. “That’s right!” he says, lifting a finger and flashing one of his characteristic Native turquoise rings. His large denim shirt is draped loosely over his shoulders, framing a squash blossom pendant necklace. It would have been impossible for either of us to divine the sequence of events that occurred in the intervening time, and which resulted in the aforementioned Bowlin playing piano and guitar on a few tracks of the record. And yet, this also seems to be a recurring motif in his story.

Knowler was born in Yuma, Arizona, a small town on the Colorado River just a few miles from the California and Mexico borders. “The sunniest place on earth,” he adds, though, I quickly find out, the narrative of his formative years there is anything but that.

His mother, a young woman looking for an escape from Manhattan, settled in the desert outpost hoping to carve out a pastoral life framed by a set of fringe ideologies — most notably a systematic distrust of the formal educational and medical systems. She met Knowler’s father at a counseling session soon after her move, and even a few years and two kids later, her resolve wouldn’t soften. So, Knowler explains, neither he nor his older brother attended school. “Not home-schooled,” he quickly adds, “but un-schooled.” When I press the matter further, trying to get a sense of what that means, he shrugs as if to indicate there wasn’t a very rigorous philosophy informing any of those decisions. “We basically spent our days riding dirt bikes and digging holes in the backyard.”

If Knowler’s candor weren’t so immediately palpable, one could suspect him of having a flair for drama, or of gleaning bits and pieces from Western novels and maybe even a Coen brothers’ movie or two — his parents gifted him a gun at age 10 — when he paints a portrait of his childhood. “So from zero to 11, basically I’d never seen anyone my own age because I was living in a retirement community. The foothills area of Yuma is where the snowbirds go — retirees that have a house in Idaho, it gets really cold there in the winter, and they go to Yuma and then they get their dental work and their cigarettes.”

The family traveled very little, and the aridity of their surroundings was mirrored in their social life. Knowler’s recollection of that period is a kaleidoscopic series of images centered around the desert, isolation, but also the quality of the light in Arizona, and the colors of the Navajo and Zuni art being sold in the market.

Unexplainedly, he attended middle school for a single year at 11 and thrived academically, rising to the top of the class against all expectations. On the last day before summer vacation, his mother met him at the bus stop, and announced that they would be moving to Texas without her husband. That night Knowler witnessed his father being carted away by the authorities, and that was the last he would see of him and of Yuma for the decade and a half that followed. Instead, his first years in a Houston suburb were again spent in aimless wandering through the city on his skateboard, smoking cigarettes with his brother while his mother’s health began steadily declining.

Knowler is a gifted storyteller, and he paints a vivid portrait of the first half of his life with the studied detachment of someone who’s spent years trying to assemble it into a coherent narrative. I have to remind myself to steer the conversation back to guitar.

When asked if he has any musical memories of that period, he takes a cinematic pause to reflect, as if to indicate that we have now entered consequential territory. He began by learning drums, then moved on to electric guitar, and quickly realized dexterity and technique came easily to him. He would play Guns N’ Roses and study the prototypical metal riffs without any real sense of direction initially. That is, until he took an organized group bus trip with his grandparents at 14.

On an overnight stop in Cody, Wyoming the travelers were given a choice between attending a rodeo or a bluegrass concert. The majority chose the obvious, but Knowler, on a whim, insisted on seeing the concert. There he witnessed a family band playing some fiddle tunes, and one of the titles, “Whiskey Before Breakfast,” stuck with him.

Knowler is not predisposed to hyperbole, and yet he makes it plain that this experience would change the course of his life. Having returned home from the trip, he looked up the aforementioned number online and the first video that came up was an excerpt of Norman Blake’s first Homespun tape. “I saw his right hand and told myself: I want to do that,” he says pointedly, “the looseness, the studiedness.” He would subsequently sell his Les Paul copy, his Parker Nite Fly and a few Ibanez guitars and buy a Japanese D-28 copy, and eventually cobble together the money for a new, 2012 D-18. He began studying Norman Blake’s music, videos — and hands — obsessively.

Knowler laughs when I inquire whether he had an inkling that this would turn into a career. “It was a total hobby, and I started making YouTube videos, like I had anything to say. Like a year into seriously playing flatpick guitar, I made tutorial videos where I didn’t know anything. And I would teach the wrong chord progression, but I loved teaching. It was basically a visual journal. I have journal books filled with like, ‘What is a triad? What is a major six?’ asking myself these very fundamental questions.”

If this doesn’t make it plain that Knowler was a preternaturally precocious teenager, the fact that he then enrolled in a community college at 16 to study music appreciation — without having gone to high school — should. “It was a battle,” he says. “Every single day it was a battle. I had to come up with fake paperwork for a homeschooling group and pretend like it had collapsed and they no longer had copies of my academic records. And then doing these entry exams and acing the writing portion and the critical thinking stuff, but my math was multiple years behind, so I had to do accelerated courses and got up to speed in about three to six months.” He would eventually move on to the jazz studies program at the University of Houston, where, incredibly, he started writing a book which he intended as a “method for rural guitarists” — a 230-page instructional manual, treatise on and analysis of the backup guitar stylings of players such as Jim Baxter, Norman Blake, Maybelle Carter and Riley Puckett.

Despite his steadfast dedication to the craft, Knowler still had planned to follow in the footsteps of some of his relatives, and enrolled in law school after having completed his jazz degree. He went so far as to take the LSAT, get accepted, and move near the campus. But before the start of the semester, after a long boozy evening spent playing tunes with a friend, he finally admitted to himself that his heart wasn’t actually in it. He was drawn to the challenge of higher education more than to an actual career in law. “I realized that, to me, the best thing about being a lawyer was just being able to say you’re a lawyer,” he quips. His friend mentioned his graduate work in archives. “And at that moment,” Knowler recounts, “I was like, I’m going to do that. That’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to do a Master’s in archives. I love archives.”

He spent a lot of time alone in that small apartment next to the law faculty building at the start of the pandemic. “I started having these vivid hallucinations of moving to Los Angeles,” he recalls. “Many came true when I finally did.” Some of them consisted in meeting a few of his musical heroes, Norman Blake included, having his favorite guitar players join him on CRK, and eventually moving to Nashville, where he currently resides.

Photo by Annabella Boatwright

Knowler’s guitar playing itself is certainly worthy of its own dissection, and it highlights the sentiment brought forth by the title of his instructional manual. While unquestionably dexterous, he doesn’t rely on speed or volume to convey virtuosity. Knowler has a sophisticated, delicate touch on the instrument and balances melody and rhythmic movement with a poise that belies, or at least transcends his youth. He is a distinctly nuanced player, but also surprisingly restrained. When I ask how he conceives of his own style, he replies modestly, “I think of it as modern, from unlikely, very disparate sources. Basically it’s a collage of American music and it’s modern.” He ponders this for a second. “I think it’s traditional to modernists and modern to traditionalists.”

When he speaks of archival work, Knowler describes the process as a reorganizing of the past in new ways, and it’s easy to see how it dovetails with his playing. On this new record, he surveys the vernacular of traditional dance music from the South, and while one can glean some of Knowler’s source influences, he manages to always sound distinctly like himself. When I mention it to him, he thanks me bashfully and explains that he re-recorded the album four or five times while moving between cities.

I ask him whether he had set out to write a collection of tunes that were either sonically or thematically connected, and Knowler nods before explaining that CRK is a portrait of his life the past few years. Harrison Whitford and Dylan Day, two of Knowler’s favorite guitarists whom he met serendipitously in Los Angeles contribute parts on the album. The same goes for drummer Jay Bellerose. The actor Jack Kilmer, who also grew up in the Southwest, narrates a poem written by Knowler. And Robert Bowlin even makes an appearance on piano and guitar on a few tracks.

I push the question of a unifying theme further, and Knowler confesses the album was a way for him to process his past experiences with hindsight, to be both the anthropologist and archivist of his own life and filter them through a brighter lens. He even went back to Yuma and experienced it with a newfound sensibility. He mentions Proust, and distance having afforded him the possibility of romanticizing his past, or at least that town.

The importance of his own experience as source material was brought to light in a convincing way when Knowler reached out to the famously private Norman Blake after having mailed him a copy of “Guitars Have Feelings Too,” and subsequently received an invitation to visit his hero at home in Georgia. “I go to Rising Fawn where Norman has been writing about Sulphur Springs (…) and going to the cemetery and seeing the last names of the people he writes about. And then his next-door neighbor is Castleberry. And having learned “Castleberry’s Hornpipe,” I realized he’s a 100-plus-year-old figure who lives right next door to Norman. I got slapped in the face almost as if I were visiting John Steinbeck, and I had seen the grocery store he went to or something like that. It’s like, ‘This is really serious. This is really the life that he leads.’ And it just changed everything on a fundamental level. I have this impulse to be the art, but I didn’t have the courage to do so because I never had someone so creatively stable in my life. But then meeting him, I just opened up the doors and I said to myself, ‘I’m just going to do this, and this is what I need to do right now’.” Knowler told Blake that his music had saved his life by giving him direction. He left that encounter with his now most-cherished instrument, the 1933 Gibson L-Century of Progress that appears on the cover of Blake’s “Be Ready Boys: Appalachia to Abilene” album. The L-Century can be heard on “Christmas in Yuma,” CRK’s first track, played by Dylan Day.

Knowler resolved that everything he would write for the rest of his life would be about, or inspired by the 100 or so mile stretch of land between Gila Bend and Yuma; a map that will unfold with each subsequent record.

“It’s like building a ship in a bottle,” he reflects, before bringing up another one of his incredible chance meetings in David Rawlings, whose approach to his own music Knowler feels a profound kinship for. He too is an apt “reorganizer” of archival material. The two met in East Nashville at a house party. Knowler picked up a guitar, played a few notes and Rawlings immediately said: “Norman.” That was all they needed to hit it off. “Dave has a good quote,” Knowler continues, “that ‘the smallest things make the biggest difference.’ (…) It’s about innovating within an existing framework.” He also means this literally in how small or unusual guitars can sound the biggest in front of a microphone. Case in point: Knowler plays a 1935 Epiphone Olympic that he acquired through Rawlings on “Mohave Runs the Colorado.” “I’m interested in the anthropology of an instrument,” he adds.

More recently, Knowler acquired a Mario Martello classical that used to be one of Bola Sete’s main recording guitars. I am curious to find out whether instruments themselves have an influence on his writing. “The beautiful thing about guitar is that it supports so many viewpoints,” Knowler answers. Referring back to the Rawlings quote, he explains that with solo guitar, you are really working in miniature, while much has been made about “sounding big” in the guitar world. He brings up the Dreadnought, which was named after a war vessel, and the Mastertone banjo as examples. “I don’t need a guitar that’s loud,” he reflects, “I need a guitar that’s introspective.” Knowler even likes what he calls uniquely unbalanced instruments that may have unusual ringing overtones, such as the 1936 Martin 00-28 he borrowed from Chris Eldridge for the track “Yuma Ferry.” “Some guitars are like a skatepark. You have to pick your tricks,” he adds, chuckling. And those proclivities even extend to recordings themselves. “In a way, I like bad-sounding records. For this medium specifically I like early Fahey records. I like what a cassette recorder does. I like what a field recorder does to the compression of a guitar.” In this as in other things, what Knowler is seeking is authenticity. In his words, he aims to cultivate depth. “Instrumental music allows you to posture yourself between photography and poetry,” he adds. It is a through line to feelings. Like photographs, they are both immediate. But words can fortify their meaning, which is why titles are so important to him.

It is certainly no coincidence that the musicians he cites as being the most influential on his playing are also unique voices whose lineage nonetheless come through in their sound. Knowler’s eyes brighten when he talks about this. “In Fahey you hear Elizabeth Cotten, and you hear Debussy. In David, to me, you hear Neil Young, and you hear Norman. And in Norman you hear Mother Maybelle Carter, and you hear Grandpa Jones, and you hear Riley Puckett.” All those people, all of us, really, are filters through which the past gets shuffled and reinterpreted. Then archived. “There is bravery in self-expression,” he concludes, “regardless of talent.”

It is getting on in the evening, but before we end our conversation I tell Knowler how impressed I am with everything he’s managed to accomplish in such a short amount of time and with very little guidance from the outside. He often refers to his stumbling upon Norman Blake’s music as a turning point in his life, but I tell him that it certainly takes a rare individual to set that kind of standard for himself as a beginner. Like a kid with a vague interest in science who would resolve to model himself after Richard Feynman without truly grasping how impossibly high he would be aiming, but also being buoyed by that naïveté instead of weighed down by expectations. And in trying to convey this, I stumble and fall short of what I intend to express. I’m still hung up on the simple fact that he managed to get into college with a year or two of schooling, never mind the rest of what he’s succeeded in doing so far — and he is still years away from turning 30. I tell him I really like the record and admire his playing. “Aw, thanks man,” he demures. “I would just like this to serve as a thank you card to Norman.” I nod and tell him I hope it reaches Blake and does that for him.

We leave on that note, and I immediately think that, more so than a card for anyone, Knowler’s story should be subsumed in his own archives as a testament to the transformative power of resilience, dedication and the story we all tell ourselves about ourselves. That there is so much more there than perhaps even he himself realizes.

But, I can already hear him say, brushing a strand of hair from his face, “Nah, that’d be like trying to take the whole ship out of the bottle.”