[Editor’s Note: Though there are plenty of rare, vintage Martins for sale, when we first got wind of a spectacular 1937 Martin D-28 headed for The Music Emporium, we knew it’d make for a great Catch of the Day entry. A guitar like this would be the cornerstone of any collection. Then, nearly around the same time, we spotted an equally drool-worthy 1934 Martin D-18H (formerly owned by Norman Blake!) over at Carter Vintage. Midway through penning a little piece about these two great instruments, I reached out to the great flatpicker Bob Minner for his take on these guitars and their accompanying demo videos. I was hoping for a few sentences comparing the sound and playability of a Golden Era D-28 to a D-18 from a seasoned bluegrass vet. What follows is Bob’s entire response, which far more insightful than anything I was going to pen. We hope you enjoy it. –Jason]

Comparing the qualities of old vintage Martins is one of the most subjective and objective things a guitar geek can have the pleasure of doing. Subjective in the sense that one’s own personal opinions and preferences color the observation. Some guys are OM lovers, some dreadnought lovers, some favor mahogany, some favor the coveted Brazilian rosewood palate. And objective in the sense that ‘30s era Martins are the most coveted guitars on the planet and they generally have “it,” albeit some more than others in terms of tone.

In short, they’re just really great and define a myriad of properties and elements that almost every guitar maker strives to draw from and emulate in an effort to capture “that sound” that entices and lures players to those ‘30s era guitars.

And so it is with two specific and rather incredible guitars up for sale at two of the finest guitar stores in North America: Carter Vintage offering the 1934 Martin D-18H formerly owned by the legendary Norman Blake, and up for grabs at The Music Emporium in Lexington, MA a stellar and uber-clean example of a 1937 Martin D-28 Herringbone (“Grail” in guitar vernacular).

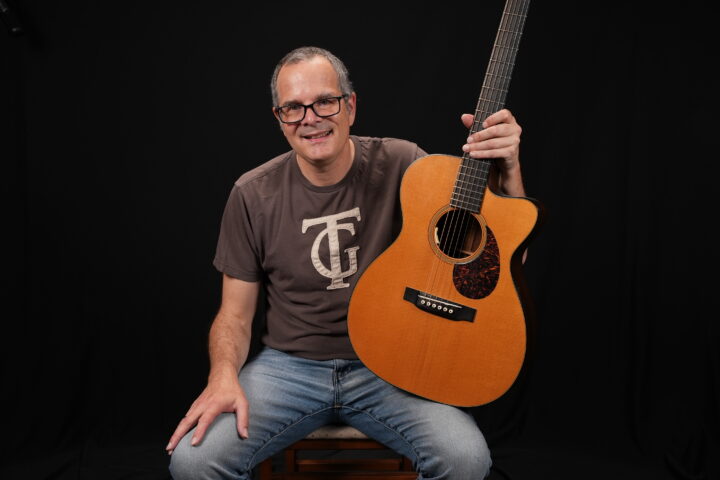

I had a chance by the good graces of Carter Vintage to play the ’34 D-18H for about an hour a few weeks ago, prior to my buddy Kenny Smith doing it extreme justice on video (which I’m sure most have seen already). And although I have not personally played the ’37 herringbone at TME, I have had the opportunity to play an equally great ’37 D-28 herringbone owned by an elderly gentleman who I grew up not too far from in Missouri on numerous occasions. And, as expected, ‘37s in this pedigree are so close in greatness, any one of them are sufficient to make observations on and be “in the ballpark,” if not at home plate.

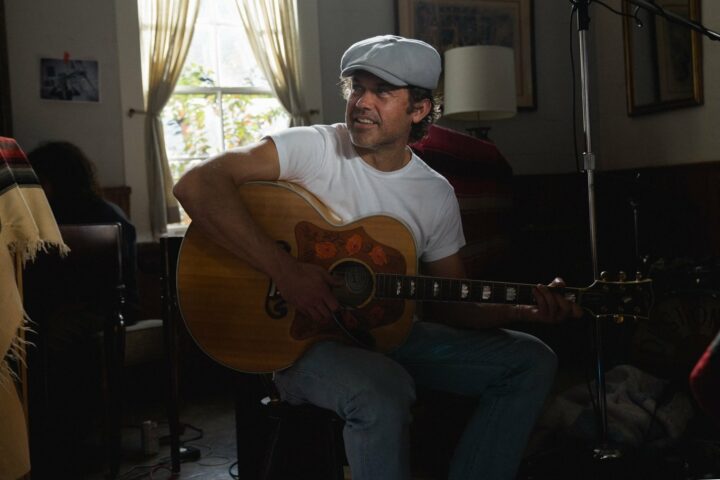

What’s interesting about comparing the Blake D-18H and the ’37 D-28 bone is that both were recorded extremely well by their respective stores, something not always done in today’s online guitar world. What I appreciated about this is the fact that in quality headphones, one could hear nuances of tone and balance, and considering the players, Kenny Smith and Andy Cambria, they brought out the amazing qualities of both guitars with a sublime subtlety that spotlighted the guitars themselves. No barn-burner stuff here, just killer playing, accenting the instrument.

On my test driving the Blake D-18H, what I found charming and in a weird way appealing was the condition of the guitar. Blake’s own modifying and slotting of the saddle was still there, as well as his trademark “outer edge” slotting of the ebony nut for both E strings. The bridge was split some. The strings, probably the very ones that were on it when Blake sold the guitar years ago, were dead as a doornail. And yet, even in that state, the guitar was spectacular. It had a depth and immediacy that was matchless to itself. There was, as Kenny also expressed to me in his playing of it, a string tension that is not often found in these guitars. And that “tension” seems to have a lot to do with its sound and projection.

There was a power in the guitar that, honestly, was inexhaustible. You just can’t drive it hard enough. It just kept giving and giving with clarity. And the lower register of bass was not a boomy, muddy 12-fret thing. No, it was full and focused, balanced across the entire spectrum of the guitar. Overall, the notes had this wonderful bloom to them. In short, it was a bucket list guitar for me to experience (I think that’s a better adjective than “play” – one experiences these sort of things). Growing up a die-hard “Blake-ite,” I had wondered since my early teens what this guitar sounded and played like. And even in its condition, it did not disappoint one iota. It is truly one that hangs on in the deepest regions of the tone bank of the brain.

As for the Music Emporium’s consignment 1937 D-28, as I said earlier, I have had time with what I consider an equally on-par ’37 Bone in my home state, so even though I haven’t personally played this particular one, I can offer some observations with a high degree of both confidence and accuracy on it.

These mid 30’s “bones” tend to be the Holy Grail amongst bluegrass / flatpicking guitarists. No secret Bryan Sutton’s ’36 D-28 is his constant go-to it seems, and for good reason. There is a presence and definition of tone in these mid ‘30s D-28s that is unrivaled by any other era dreadnoughts. My experience with the MO ’37 was one of just having it all across the board. The articulation, immediacy, bloom and sheer power of the guitar really brings to the forefront exactly why they were dubbed “dreadnought.”

Andy Cambria’s playing of TME’s example, one of only 148 made in 1937, really brought out the greatness of this guitar. It’s exactly what I expected. There is such a richness to every note – it just hangs on and decays perfectly. The highs are fat and thick, and overall every note over the entire guitar is like it was computer generated for perfection on every level. And I’m sure there was no limit to the headroom of this particular guitar.

So in the end, I applaud both Carter Vintage with Kenny Smith and The Music Emporium with Andy Cambria for recording and playing these stellar instruments in a way that showcases them for the world in a respectful and almost archival way. Count yourself fortunate to handle such guitars. I know that I personally do. I own a 1936 D-18 that, like these other ’30s guitars, is yet another benchmark for this era of instruments. And I think when one gets into the realm of playing and experiencing (there’s that word again) these Martins from the hallowed era of the 1930s, their similarities are more apparent than their differences. Great becomes subjective to the player and listener. Great becomes objective because, well… they’re just great guitars.