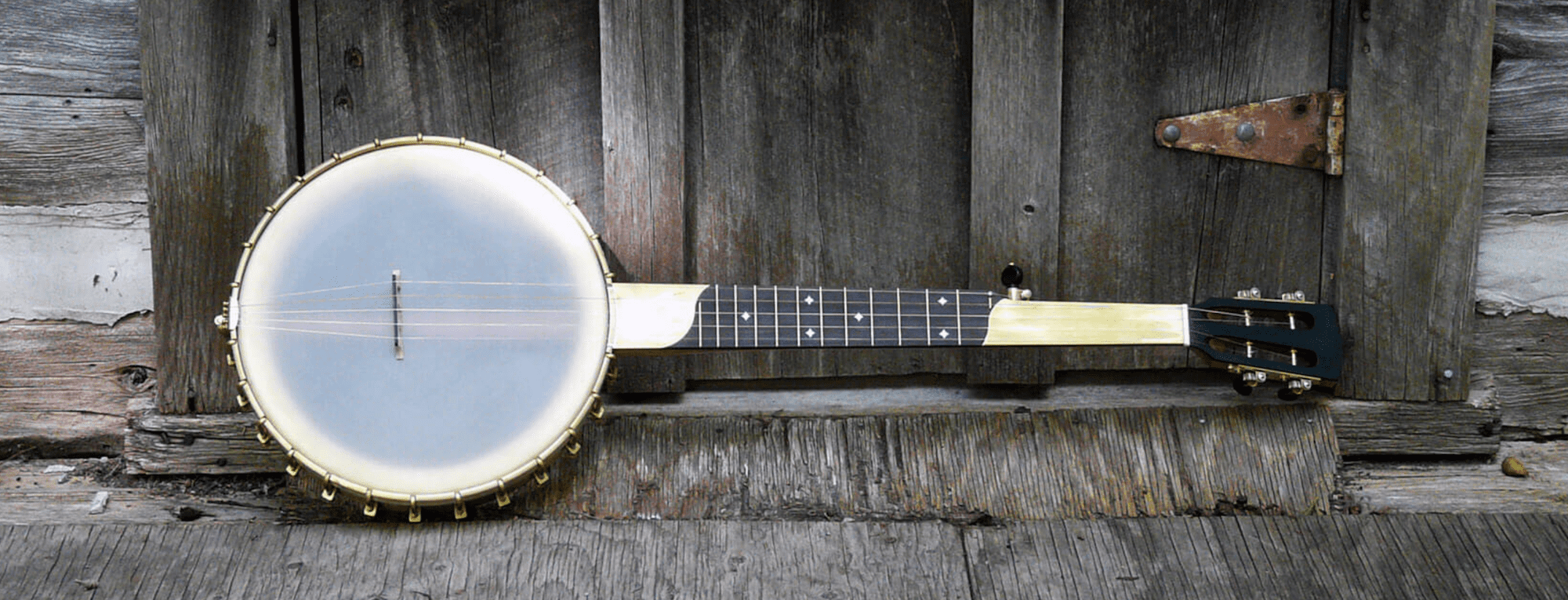

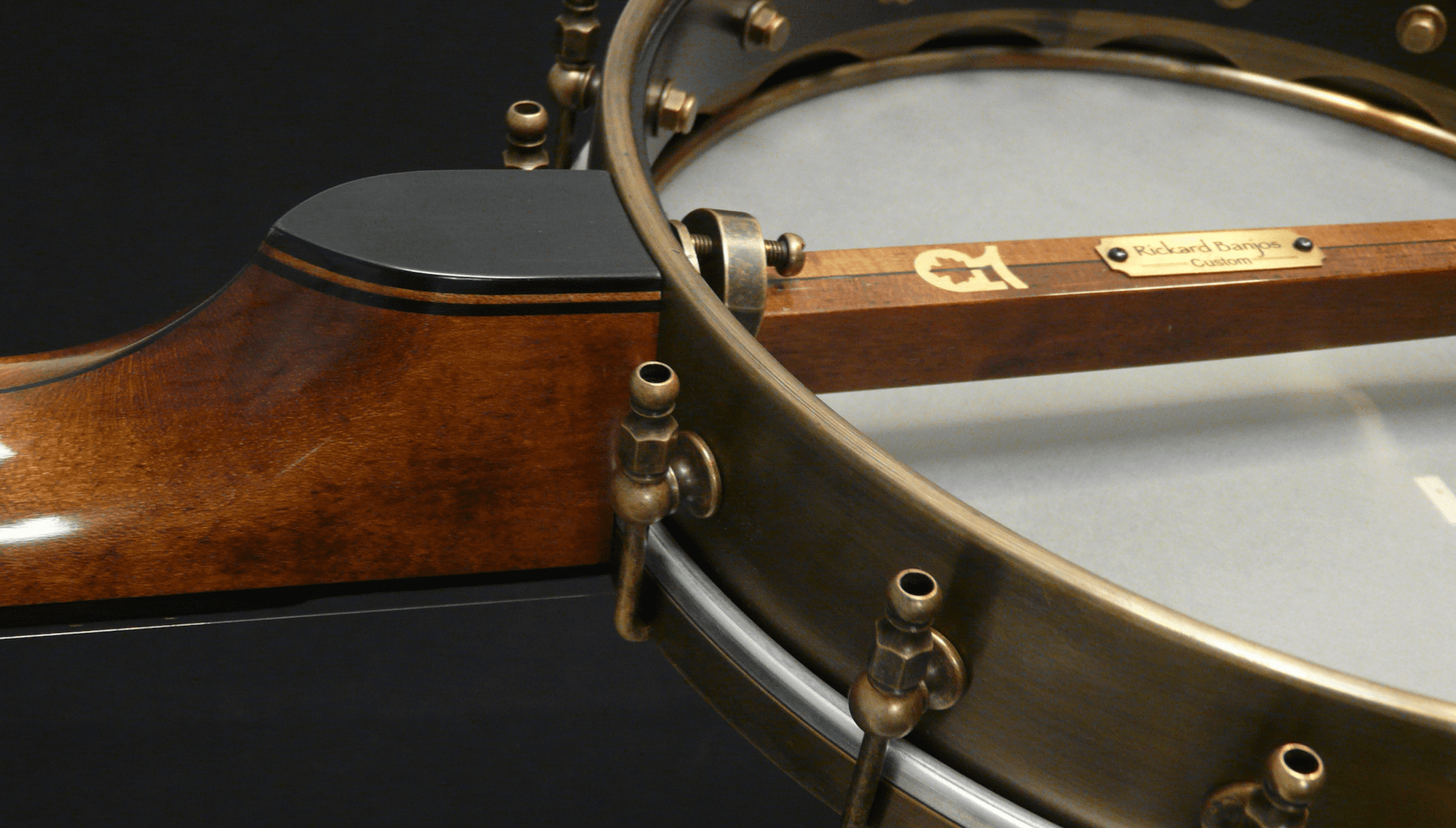

Banjo builder Bill Rickard is truly one of the most innovative builders in the luthier world. At his shop in Aurora, Ontario, Canada, he’s constantly coming up with new parts, rim constructions, and tone rings among other things that take advantage of the modern technology available to him while keeping tradition firmly at the heart of what he does. In this edition of Bench Press, Bill tells us about how his past life in manufacturing and a life-altering accident led him to become one of the most renowned banjo builders in the world.

Fretboard Journal: How did you get started?

Bill Rickard: I started back building guitars when I was 16 years old because I was learning to play. I had one of those deals where you got a lesson and a plywood guitar, but I realized quickly that I needed a much better instrument. My dad was a woodworker and he said I either had to get a job and buy one or build one myself. I thought he was crazy, but I decided I’d show him. That first one was very playable, but once you build one, it’s impossible not to build more. From there I started building and taught myself to do repairs for some local music stores. Then I got into bluegrass and I wanted to play banjo, so I decided I’d build one. I actually still have that first banjo. Back in the ‘60s when I was doing this, there was no internet, so I had to go to the library and read anything I could find. I was getting most of my parts from Stewart-MacDonald.

I kept building instruments as a hobby until I was about 25. It helped me pay my way through school and always gave me a bit of spare money in my pocket. I was still buying all my hardware at that point, which I don’t do anymore since I started making most everything myself. Then I got married and had a family, had a mortgage to think about—the whole bit. I decided it was impossible to pay my way by building instruments, so I got involved in construction. I still played music, but I wasn’t building anymore. Eventually I ended up running my father-in-law’s manufacturing company when he passed. They did industrial automation which is important because it taught me to design equipment.

Then when I was about 48 years old, I went into a music store around Christmas time to get presents and I saw Chris Coole and Arnie Naiman’s album, Five Strings Attached with No Backing. I looked on the back and saw that the record company, Merriweather Records, was in my town. So I called them up about taking lessons and started with Chris Coole because I already played three-finger bluegrass style, but I wanted to play old-time in the clawhammer style. I started playing three or four hours a day—whenever I had a spare moment. Chris and I became really good friends and he sort of took me under his wing and got me back into music, but I really only thought I’d build again after I retired.

FJ: What changed that got you back into building?

BR: I played up until I was 57 years old when some friends and I decided to go on a motorcycle trip to Italy where I learned what people meant when they say your life can change in a second. The first day we were there, we picked up these new Ducati motorcycles and were riding all over these small towns. All of a sudden, an aggregate truck crossed over the center line of the road and hit me head on. I went over the roof of the truck and landed back on the road. I remember trying to move so I didn’t get hit by a car, but I couldn’t. I was in shock so I didn’t know all this until later, but my left arm and leg were gone on impact. Luckily, someone saw the accident and called the little country hospital up the road. They sent an ambulance and I remember coming in and out of shock in there. They’d yell at me in Italian and I’d tell them I only spoke English, but then I’d pass out again.

A doctor at the little hospital was able to keep me alive long enough to have me airlifted to the university hospital in Pavia, and he told them he’d never seen someone with that kind of blood loss come out of it alive. I found out later that my chest had completely split open and they could even see the artery over my heart. Weirdly enough, the doctor at the little country hospital, after getting me the airlift, got a call that his son had been in a car accident—he had hit a motorcyclist.

I was in the hospital for a long time and I went through hell. I lost my left arm out of the shoulder joint and my left leg out of the hip joint, which I was told is just not the kind of injury you’re supposed to recover from. I was really depressed, but then people started to visit me. Chris Coole put the word out about my accident, and I was getting visits and gift baskets from all these people I’d never met. One guy even sent me a gift basket full of harmonicas. Having all these people I didn’t know come visit me, bring me gifts, play music for me—it really changed me. I only saw maybe one or two of my friends from business, the rest were musicians. I think that anyone involved in the arts and music just tend to be compassionate people.

When I was recovering at my home in B.C., it clicked with me that I didn’t want to go back to my business when I was better. Like I said, I figured I’d start building instruments again when I retired, but I decided to do it then just to see if I could do it with one hand. I ended up building a few banjos for Chris Coole, and it just sort of took off from there. That’s the short of it.

FJ: Can you tell us about your shop?

BR: We actually just moved. We were sharing a building with my main manufacturing company, but I’m mentoring a young man to buy the company and take over for me in a few years. We just moved back to a building I used to own and it’s a big place—55,000 square feet that is part manufacturing, part banjo shop. I’m actually looking at another facility to get the banjo shop a bit of distance from my manufacturing business—that’s just sort of my past life.

I’ve made all the parts besides strings, fret wire, and tuners myself in the shop, and we’ve since been starting to make our own tuners. I came up with methods to make everything with one hand. Like I said, I really didn’t want to go back to the work I had been doing before my accident, but I knew I’m not made up to ever retire. So I started making some pretty high-end banjos for my friends. Now I have three or four fellas in there with me. I’ve got all the equipment in there that I need. I got myself a Swiss turn lathe, which is like a CNC screw machine. I also got a CNC machine which I use to rough cut the necks before we take the fine parts down by hand, and we have some big lathes. I brought a bunch of machines from my old shop for the sole purpose of building instruments, which is why I can make so many of the parts that go into them. I make the rim bolts and the washers all myself so that I’ll know they fit absolutely perfect. Anything you see on my website has been made in our shop. We’ve got it all dialed in now. I could do everything by myself, but we just got too busy with orders.

FJ: Are there any other upcoming projects you’re particularly excited about?

BR: One of the last things I had to learn to make was my own tuners, so I started building what are pretty standard banjo tuners, 4:1 planetary tuners with six tooth gears on the inside. But then I decided to try 12 tooth gears in stainless steel. We cut every part of the new tuners and made a couple thousand of them, still 4:1 turning ratio. But I thought 4:1 doesn’t really sound right, yet it’s all you can get in a planetary banjo tuner. So, I started working with a guy I met through Banjo Hangout named Mike Rowe to build something different.

He does a lot of work in the automotive business and he really knows how to draw in three dimensions, which is kind of my weakness, but it’s important to know in designing something like a tuner. I got the idea to use something I knew of from my time in the automation industry called a cycloidal gear box. My friend Frank Ford of Gryphon Stringed Instruments in Palo Alto, California told me he had been trying to do this for ten years, but the difficult thing is that with a cycloidal gear box, when you turn, in this case, the tuner button one way, the string post spins the other. In big motors, this is easy to correct because you can just rewire the motors, but it’s hard when you need to get it down to fit inside a tuner. It took three years and fourteen tries to get it, but I finally did. These new tuners are 10:1 in the same size as a traditional planetary tuner, but the difference is that, on 4:1 tuners, when the tuning button comes loose, the string unwinds and detunes. With these, you can take the button right off and nothing will happen.

We’ve got all these vintage guitar players calling me now because Martin used to build their OM model with planetary tuners. People love the look of them, but hate how difficult they can be, so they’re excited that these 10:1 tuners don’t backwind. We can even turn them into 16:1 turning ratio just by changing two little parts in the case. We’ve been testing them for over a year. I put them on this system I built and ran them for something like 34,000 revolutions, and when I took them apart, there was virtually zero wear. I decided to put a patent on them just because we’ve put so much time and effort into them and we got them perfect. They’re so smooth, they don’t slip, and you don’t need to drop them down and raise them to pitch the way you normally do with a tuner. With these, it doesn’t matter if you tune up or down, they land on pitch and stay in tune every time. I sent Frank Ford some a while back to try selling in his store, and he called me the other day and told him I needed to send more—they sold out right away! We haven’t even advertised them yet, but the word has got out about them. Now we’re making 5,000 sets, so this is major for us. We’re pretty sure this is going to change the whole industry.