The sprawling Intégrale Django Reinhardt, Volumes 1 through 20 (Frémeaux et Associés) is a massive, amazing tribute to Django Reinhardt’s life.

The basic outline of Django Reinhardt’s remarkable career is familiar to just about anyone who loves the guitar: how he started playing guitar-banjo as a child in the bals musette, the rough, working-class dancehalls of Paris; how he nearly lost his life in a fire that badly burned his left hand; how, in the process of relearning to play guitar with his crippled hand, he developed a mastery of his instrument that still astounds other guitarists; how he formed the Quintet of the Hot Club of France with violinist Stephane Grappelli and created the style now known as Gypsy jazz; and how, after filling hundreds of records with his astonishing music, he retired to the little village of Samois, where he died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1953 at the age of 43.

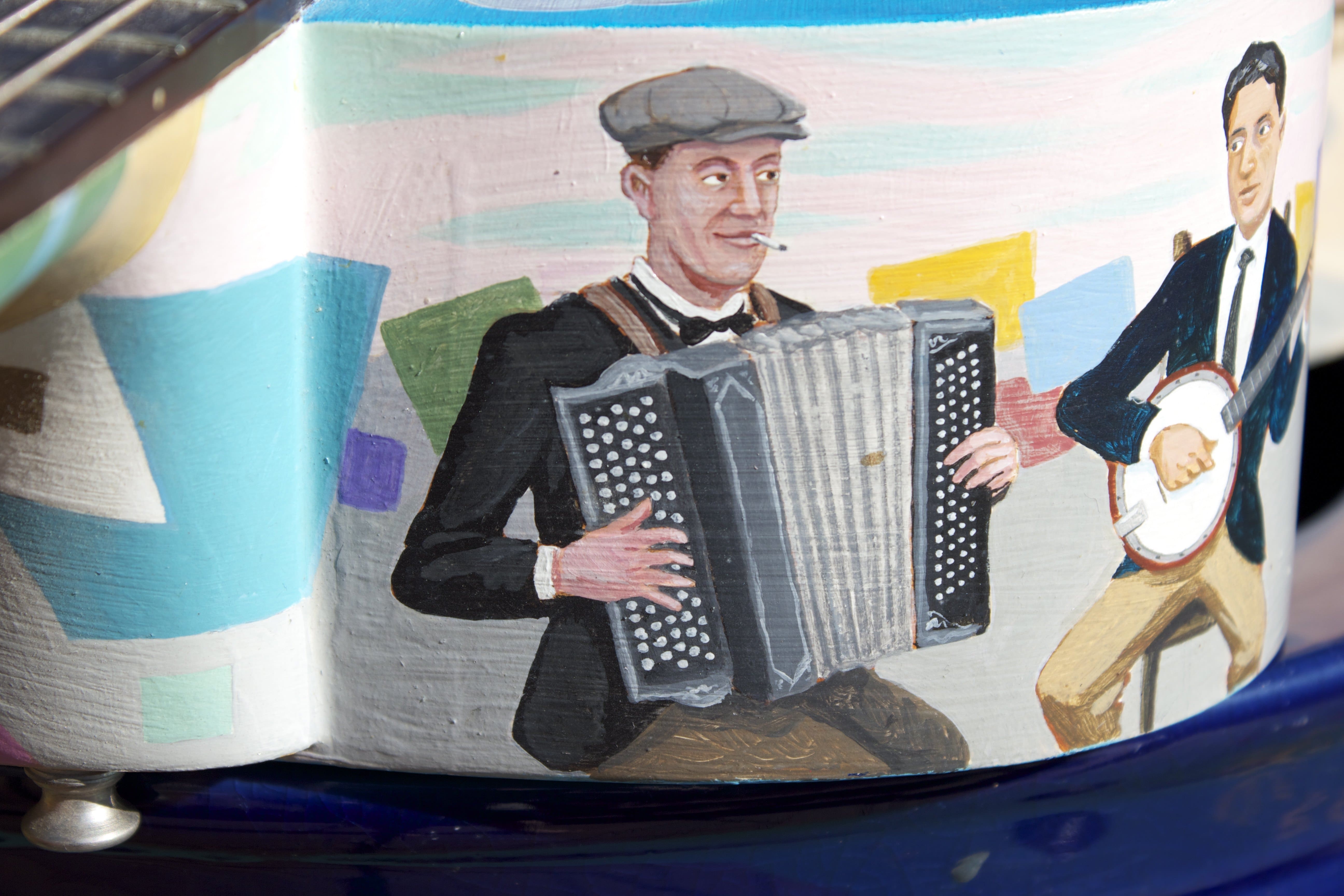

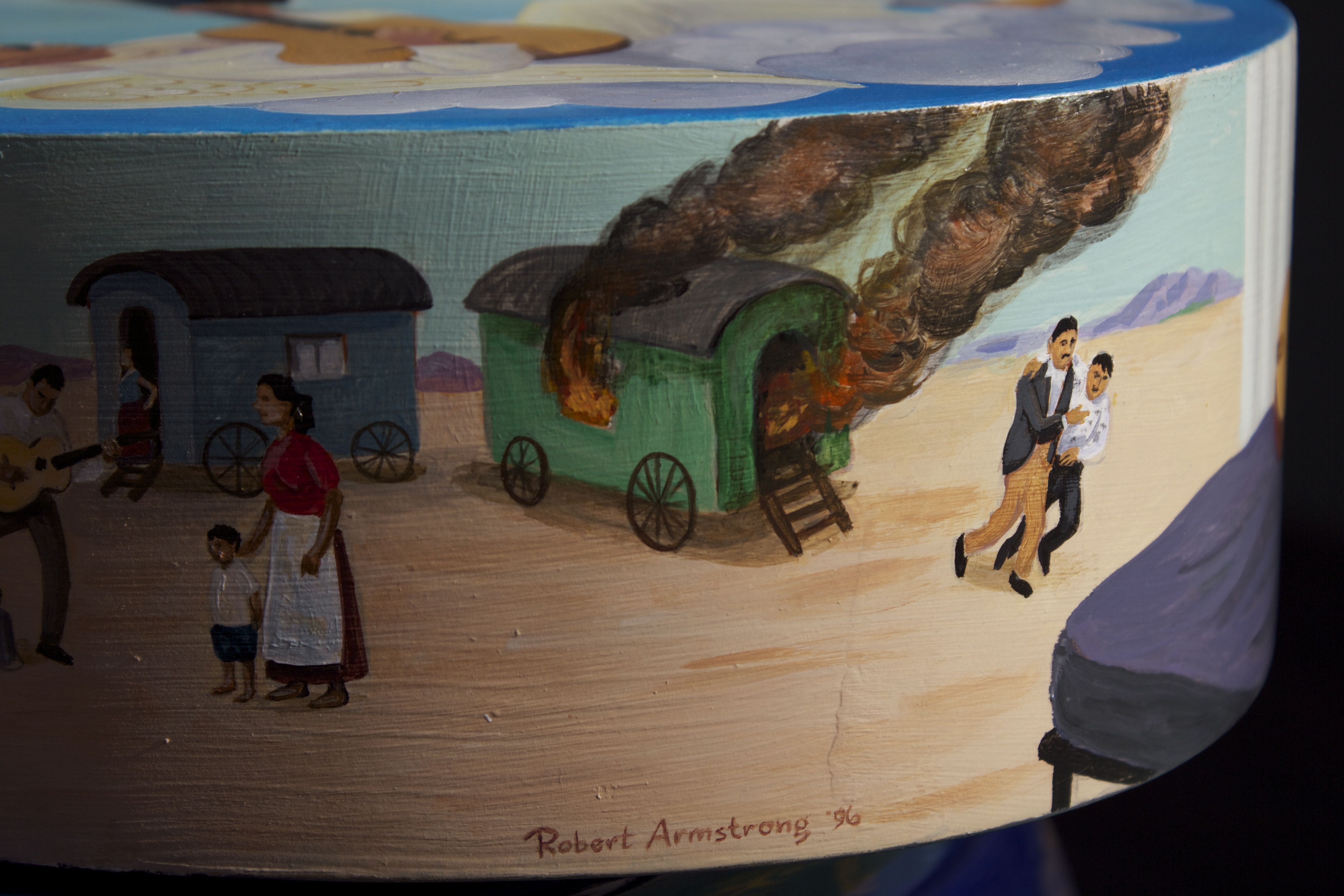

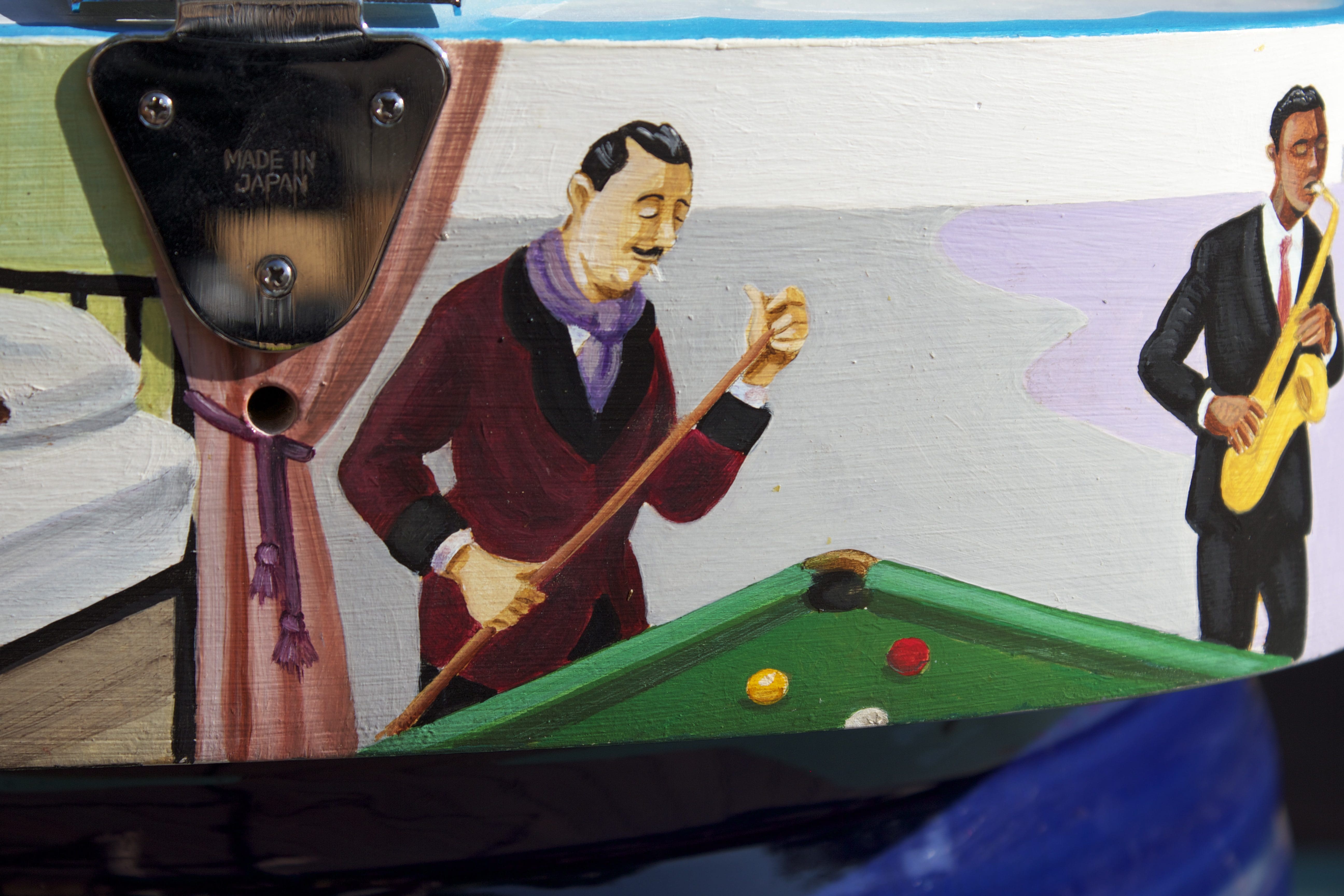

The Django Guitar above was painted by Robert Armstrong.

Most fans also know that Reinhardt made a lot of records, but until the release of Intégrale Django Reinhardt, they probably weren’t aware of how prolific he really was. This series of 20 two-CD sets was compiled by Daniel Nevers and includes every commercially released recording that Reinhardt played on as a leader or a sideman, as well as every known private recording, air check, test pressing and outtake. The mammoth task of rounding up the more than 900 tracks Reinhardt recorded in his lifetime was begun in 1996 and completed in late 2005. Reinhardt was a man who lived for music, and we’re fortunate he lived much of his life in front of a microphone. The Intégrale Django Reinhardt is a sort of biography through music and it tells Reinhardt’s story more profoundly than mere words can.

People who only know Reinhardt from his work with Stephane Grappelli will be surprised to discover how many records he made before the two men formed their famous Quintet in 1934. Volume 1 begins with the session from June 20, 1928, when Django Reinhardt first stepped into a recording studio to play backup guitar-banjo for the popular accordionist Jean Vaissade. Reinhardt was only 18 years old, but he was already a seasoned veteran, one who had started his professional career at the age of 12. The four sides Reinhardt and Vaissade recorded that day were typical of the tunes played in the dives in the rougher areas of Paris. The selections included “Ma Régulière,” an instrumental version of a current Maurice Chevalier hit; “Griserie” and “Parisette,” two tunes commonly heard on the barrel organs played by street musicians; and “La Caravane,” a melody from a then-popular operetta.

Vaissade was so pleased with the session that he invited Reinhardt back into the studio a few days later to record six more sides and he even gave the young prodigy credit on the record’s label. (As Reinhardt was illiterate, he didn’t notice they misspelled his name as “Jiango Renard.”) Other musette accordionists noticed Reinhardt’s playing, and soon after his Vaissade sessions, he cut one side with L’Orchestre Alexander and four tracks with Victor Marceau, who, in what was fast becoming a tradition, misspelled Reinhardt’s name as “Jeangot” on the record’s label. On each of these rare tracks–even Reinhardt said he never heard the Victor Marceau recordings–the young banjo player exhibits an astonishing command of his instrument, and his inventive playing and audacious countermelodies threaten to overwhelm the accordionists he was supposed to be supporting. The recordings are crude, the instrumentation is odd–some tracks include slide whistle and xylophone–and, at the dawn of the Jazz Age, the music was rapidly becoming archaic. But there is a real magic in these cuts.

Tragically, the magic almost ended on October 26, 1928, when Reinhardt’s caravan caught fire and his left hand was badly burned. Reinhardt lost the use of two fingers, but during his convalescence he re-taught himself to play guitar and emerged from his sickbed an even more brilliant player. In 1931, Reinhardt returned to the recording scene when he cut three sides with accordionist Louis Vola, who led a popular dance band in the south of France. By now, Reinhardt had switched from banjo to guitar and, thanks to Vola’s connections, the young guitarist began to find recording work with other dance bands and popular singers, as well as regular, well-paying work in high-toned nightclubs and hotel ballrooms. It was at one of these gigs, at the fancy Hotel Claridge, that Reinhardt met the violinist Stephane Grappelli, and the two men struck up an immediate friendship. During the next few years Reinhardt honed his guitar skills as a sideman on dozens of records, including some with Jean Sablon, a popular singer who had an intimate crooning style that has been compared to Bing Crosby’s. It was at a Sablon session in early 1934–one that featured a French-language version of the Disney song “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” of all things–that Reinhardt first recorded with Stephane Grappelli, who was playing in the string section.

Volume 2 finds Reinhardt backing more pop singers and dance orchestras, but apart from the occasional solo break, he tends to get lost in the mass of sound. But this CD does include some fascinating glimpses of the birth of the Quintet of the Hot Club of France. In August 1934, Reinhardt, his brother Joseph and bassist Juan Fernandez cut three demo discs of the standards “Tiger Rag,” “After You’ve Gone” and “Confessin’,” which, while well-played, sound a bit too tentative and were not released at the time. At another test session two months later, though, it was a completely different story. This time Reinhardt and his brother were joined by Grappelli, guitarist Roger Chaput and Louis Vola, who had put down his accordion and taken up the bass. Credited as Delauney’s Jazz (after the French jazz promoter, Charles Delauney, who had arranged the session), the new quintet backed singer Bert Marshall on the song “I Saw Stars” and played an instrumental version of “Confessin’.”

The five musicians immediately knew they had something special, and so did Delauney. On December 28, 1934, he arranged another recording session for them, and the Quintette du Hot Club de France was officially born. In keeping with dubious tradition, Reinhardt’s name was misspelled on the label, this time as “Djungo Reinhardt.” When the four sides were released–“Dinah,” “Tiger Rag,” “Lady Be Good” and “I Saw Stars”–they caused a sensation in French jazz circles that soon spread to the international jazz world. In Reinhardt and Grappelli, Europe had at last produced world-class jazz musicians–and, as a bonus, the all-string makeup of the Quintet introduced new rhythms and unique sonic textures to the jazz vocabulary.

Volumes 3 through 9 trace growth of Reinhardt and Grappelli’s unique musical partnership and the maturation of the Quintet from a hot swing band that played jazz standards like “Sweet Sue,” “Avalon” and “Limehouse Blues” to a vehicle for Reinhardt’s own brilliant and enigmatic compositions. This is the most famous material Reinhardt recorded, and if you already have a Reinhardt CD or two, it’s likely that most of the material was drawn from the 1934 to 1940 period covered here. Even if you have all of the Quintet’s recordings, there are many rare and wonderful nuggets to be discovered here, such as the snippet from a 1937 BBC jazz show that includes an embryonic version of “Minor Swing,” then known as “Fat.” There are alternate takes of Reinhardt compositions such as “Hungaria,” “Twelfth Year” and “Boléro” plus a charming duet from 1940 with accordionist Gus Viseur–something of a homecoming since it was the first time Reinhardt recorded with a musette musician since 1933. Reinhardt still continued his session work with dance bands and pop singers, but now he was given featured solos.

Volumes 10 through 12 cover the War years, a terrible time for France, but, oddly, the period when Reinhardt came into his own as a composer. Grappelli had been stranded in London at the start of the war, and Reinhardt had reconfigured the Quintet in his absence. Instead of three guitars, violin and bass, the new Quintet had Joseph Reinhardt on rhythm guitar, a drummer, a bassist and clarinetist Hubert Rostaing. The new lineup seemed to shake something loose in Reinhardt and in short order he was turning out original tunes like “Rythme Futur,” “Appel Indirect,” “Swing 42,” “Manoir de mes Rêves” and, perhaps his greatest composition, “Nuages.” Reinhardt’s compositions from this period drew on the musette of his youth, the Gypsy music of his Manouche tribe, the jazz he’d been playing for the past decade, classical composers like Debussy and Berlioz–and his own eccentric genius.

The melancholy melody of “Nuages” seemed to touch something in the Parisian spirit and it became a sort of wistful anthem for war-torn France, a reminder of happier times. A version with lyrics by Jacques Larue was recorded by singer Lucienne Delyle and became a wartime bestseller. Over the years Reinhardt would keep returning to this tune; in fact, there are 13 versions on this collection. After the war was over, Grappelli returned to France, and the two friends started playing together again. Their reunion record was a swinging take on “La Marseillaise,” which caused a minor controversy when it was released, as many felt it was disrespectful. Grappelli and Reinhardt released a handful of records at this time, but during their separation their styles had diverged. Grappelli was moving towards a sweeter, café style of jazz while Reinhardt began experimenting with bop, and while the music sparked from time to time, it never really caught fire like it did in the 1930s.

In 1947, Reinhardt and clarinetist Hubert Rostaing began recording for Blue Star, a new label started by Eddie Barclay. The swing of the 1930s had given way to the modernistic sounds of bop, and nobody was really sure what was going to sell. Barclay let Reinhardt choose his own material and, more surprisingly, record with an electric guitar. Volumes 14 and 15 include the Blue Star sessions, which show Reinhardt toying with the new bop vocabulary. These two volumes also include a large number of tracks recorded for radio, which feature the Quintet in a looser, blusier mood than ever before.

Later that year, Grappelli and Reinhardt reunited for a series of concerts and radio shows, and, as with the earlier reunion, the music was pleasant and well played, but not truly inspired. Still, these shows led to a long stay in Rome in 1948, where Grappelli and Reinhardt recorded dozens of tracks for Italian radio. The backing band for most of these sessions, though, wasn’t really up to the high standards the two old friends were accustomed to. As Volumes 16, 17 and 18 show, Reinhardt seemed most inspired when he played alone, as he did on “Improvisation #4,” or when he played in a duet with Grappelli, as on “Manoir de mes Rêves.” In February 1949, Grappelli and Reinhardt entered the studio at the Italian radio station RAI, recorded a handful of jazz standards and, as far as anyone knows, never played together again.

After that final session with his old partner, Reinhardt found himself in a quandary. He was interested in pursuing the modern sounds coming from America–he jammed with bop pioneer Dizzy Gillespie, for example, though, sadly, they never recorded together–but his older audience only wanted to hear the prewar chestnuts. At the same time, the younger audience dismissed him as a relic from an earlier time and ignored his new direction. So, rather than fight the public, he retired to a little house in the tiny river village of Samois-sur-Seine, 60 kilometers south of Paris, where he spent his days fishing and playing billiards.

From 1950 to 1952 he only made a handful of recordings, mostly for radio. Volume 19 includes these sessions, which actually include some of Reinhardt’s most interesting work. In 1950, for example, he recorded a seven-minute solo version of “Nuages,” an impressionistic recasting of his most famous tune that was unlike anything else he ever put on disc.

In 1952 and 1953, it seemed like the world was poised to rediscover Reinhardt. He made a handful of records for Decca and Blue Star with young musicians who could (almost) keep up with his intense playing. Reinhardt showed that he was not a relic, but instead a master improviser with an uncanny ability to effortlessly spin out brilliant idea after brilliant idea. These tracks, which include selections such as “Anouman” and “Troublant Boléro” played on electric guitar, are considered by modern Gypsy musicians like Stochelo Rosenberg and Biréli Lagrène to be some of Reinhardt’s finest recordings.

Volume 20 includes Reinhardt’s last sessions. In March 1953, he recorded eight tracks for Blue Star, including a haunting final version of “Nuages” played on electric guitar and a bluesy take on “Confessin’,” a song he first recorded in 1934. Reinhardt’s final recording session was on April 8, 1953, and consisted of four selections. The last song he recorded was his own composition, “Deccaphonie,” a complex, simmering tune backed by Martial Solal’s piano and Sadi Lallemand’s vibraphone. The following track on the CD is a recently rediscovered record from 1928 that features an 18-year-old Reinhardt backing up the musette accordionist Alexander. It’s difficult to imagine that the young Gypsy playing banjo on this antique tune is the same musician who played the still-modern-sounding guitar lines of “Deccaphonie.”

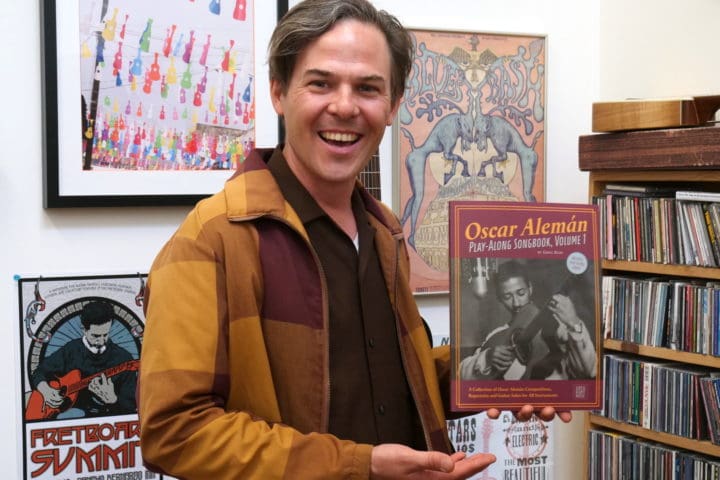

Among the rediscovered rare tracks that fill out Volume 20 are two takes of “Chinatown, My Chinatown” by the 1935 version of the Quintet and a track with Duke Ellington from 1946. Also included is a selection of cuts from Reinhardt’s contemporaries and associates, including his brother Joseph, his son Lousson Baumgartner-Reinhardt, his friends Baro and Sarane Ferret and the Argentine guitarist Oscar Aleman, who offers a nice version of “Daphné.”

Intégrale Django Reinhardt is a massive undertaking. All of the famous tunes are here, but there is so much more to Reinhardt’s legacy than “Minor Swing” and “Nuages.” It is well worth the time for serious Reinhardt aficionados and guitar historians to delve deeply into the project’s more obscure selections. The extensive liner notes are full of anecdotes that help illuminate his life, as well as loads of rare photos and extensive discographical information. The remastering is excellent where there was good source material, and even when dealing with well-worn acetates or obsolete technologies like wire recordings, the sound is still listenable. The set is dotted with never-before-issued tracks, and, with a player as good as Reinhardt, every new scrap is worth savoring.

Django Reinhardt died on May 16 was laid to rest on May 19, 1953. In an absurd footnote, the stone carver misspelled Reinhardt’s name as “Djengo” on the gravestone. It has since been corrected–and his fame since secured. It’s unlikely anyone will ever misspell Django Reinhardt’s name again.

For more information on Django Reinhardt check out Michael Dregni’s excellent books

Django: The Life and Music of a Gypsy Legend

Django Reinhardt and the Illustrated History of Gypsy Jazz

Gypsy Jazz: In Search of Django Reinhardt and the Soul of Gypsy Swing