“Drop all your worries about authenticity,” says Jack White just before playing an encore to his closing set on the second of three nights at the 55th annual Newport Folk Festival. “Authenticity is a phantom. It’ll suck the blood out of you. It’s about the music [artists] play, is it not?”

By eschewing any measure or definition for the music performed at the annual celebration on this glorious, oceanfront patch of earth in Rhode Island, White may have articulated what has made the Newport Folk Festival so successful in recent years. Since 2008, Jay Sweet, a journalist and film music supervisor, has booked a broad mix of artists whose music he describes simply as sharing a “common root.” That root, American music, may be presented in the form of a sensitive singer songwriter and acoustic guitar, flailing country-influenced punk rock, blues, or bluegrass. If it serves the narrative of the musical history of the US, it’s welcome in Newport. As Louis Armstrong famously (and perhaps apocryphally) said, “It’s all folk music; I ain’t never heard no horse sing.” But, I’m guessing if a horse could tap out a back beat, it would be welcome on the Newport stage.

In addition to the wide range of “roots” music wafting through the sea air, other elements of this festival summon the arts lover. The physical setting, with the Civil War-era Fort Adams as a backdrop to the main stage and the sailboat-filled harbor as the view from that stage, are without peer in the concert circuit. In addition, the peninsula in which the Fort Adams State Park sits accommodates only 10,000 people, making this a very small festival given the talent it attracts. So, just how do you pay the going rate to over sixty acts if you’ve only got 10,000 paying customers? You don’t. Given the gear that they drag along, the headliners typically lose money on the weekend. But, they line up for the opportunity not only for the prestige, but for the relaxed and warm vibe ever present on these grounds.

White waxed eloquent about that vibe, noting that this afternoon had been the first time in a dozen years that he was able to “walk around and watch bands without people annoying me.” Indeed, many if not most of the performers can be seen wandering the grounds when not playing. At Newport, well, you just don’t bother the stars for a selfie or an autograph. No one wants to disturb the vibe.

So, let’s make like Jack White (the hipster hat and makeup are optional) and wander the grounds of Fort Adams State Park. We’ll stop in to revisit some of my favorite performances and, hopefully, discover some of the attributes that make the Newport Folk Festival so special.

A Unifying Force

So, you’re thinking as we begin our stroll, what holds all these disparate bits of music together? This year the Festival sports a powerful, unifying force in the form of Mavis Staples, who first performed at the Festival in 1964 as part of her family band, The Staples Singers. She’ll be back to headline the closing evening and to celebrate her 75th birthday.

But, when I arrived on Friday afternoon, word at the press tent was that Staples was already on site, two days before she was due. The reason became clear early in the day: if you’re to unify, you need to seem to be everywhere at once. Staples first appeared before the public mid-afternoon when she took the stage to join Lake Street Dive on “Bad Self Portraits,” the title track their recent album. Evidently a fan, Staples led off the performance by singing the first chorus, then yielded to Rachael Price and stepped back to sing harmony, rejoining Price in a final chorus.

Staples performed with another youngster, and his youngster. Jeff Tweedy, with a band featuring his son Spencer Tweedy on drums, played a set that spanned his career from Uncle Tupelo to Wilco to his solo career. Staples joined Tweedy for “only the Lord Knows,” a Tweedy composition that Staples recorded on her recent Tweedy-produced album, and John Fogerty’s “I Wrote a Song for Everyone.” Augmenting the gospel and alt-country vibes supplied by these two and adding an exclamation point to the all-encompassing aesthetic, Jess Wolfe and Holly Laessig of the band Lucius, supplied backing vocals while flaunting a bit of Vegas in the form of glittery dresses and blond wigs.

Staples also materialized Saturday afternoon when mid-set she joined Puss n Boots, the alt country band comprising Norah Jones, Sasha Dobson, and Catherine Popper. Standing front and center, Staples sang gruff harmonies on a cover of the Band’s “Twilight” before scat-singing a final chorus while Jones beamed in obvious awe.

Apparently as pleased as was the audience with the collaboration, Staples welcomed “little bitty Norah Jones” for two songs during her Festival-closing set Sunday evening. First, along with members of Trampled by Turtles, Jones stepped on to the Main Stage for a moving rendition of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?” Then, as the Turtles crept off and Dawes’s Taylor Goldsmith stepped on, Jones sang the opening verse of The Band’s “The Weight.” Staples sang a couple of verses and then affectionately conducted her young admirers.

“The Weight’s” quasi-religious lyrics set the tone for Staples’s almost-spiritual set. Sure, she sang gospel songs like “Will the Circle be Unbroken” and “I’ll Take You There,” the latter including Spooner Oldham on organ who, as part of the Muscle Shoals rhythm section, played on the Staples’ 1972 original. But, beyond the occasional lyric, there was the transcendent tone that had the crowd swaying and shouting encouragement. She presented a wide-ranging set that included the Talking Heads’ “Slippery People” and Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth.”

Staples unified not only the disparate musical elements of the Festival, but bridged the past with the present and by sharing the stage so often with younger musicians, pointed the way toward the Festival’s future.

Pandemonium

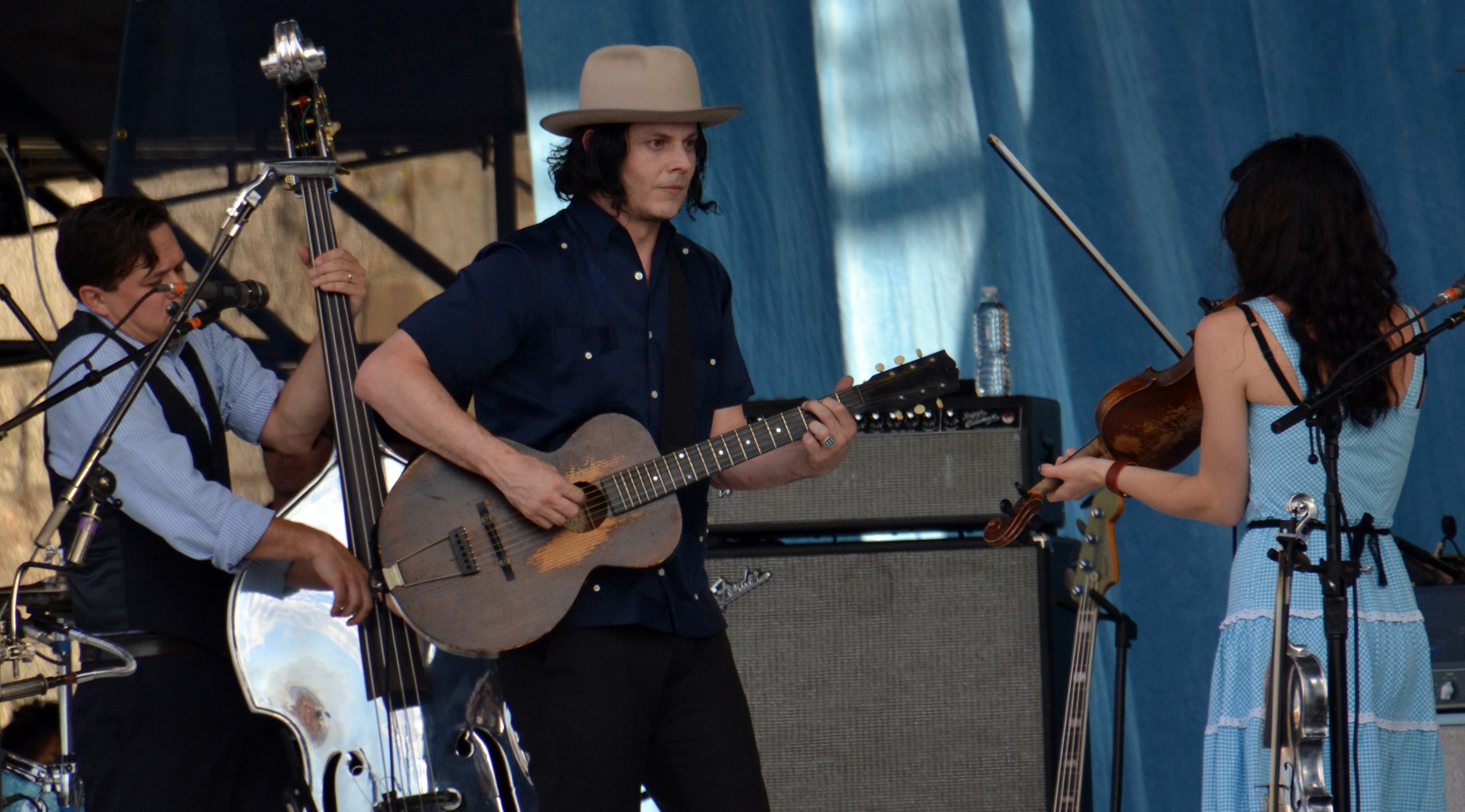

Mavis Staples, as the godmother of gospel and soul, cut a stately figure. The prior evening’s headliner – he who eschews the authentic – was anything but stately.

A Jack White performance is a sound and sight to behold. When asked whether White is a genius or simply a sloppy guitar player, a friend emphatically responded, “Yes!” The same question and answer would be appropriate to the perplexing rocker’s hour and a half Newport set. It, like all White performances, was an exercise in mania. He jumped from spot to spot and instrument to instrument, letting one guitar drop to the stage floor as he grabbed another while motioning a band member to switch off the still caterwauling, abandoned instrument. The songs, themselves, verged on disintegration as White sped up and slowed down tempos, launched mid-song into other compositions, or stopped time altogether. But for the keyboard player, to whom White would occasionally whisper the title to the next song, the band members scrutinized their leader intently for signs of what was to come next.

What did come next after the opening White Stripes’ number, “Dead Leaves and the Dirty Ground,” was a jumble of songs from the entirety of White’s career, including over half a dozen Stripes’ tunes (including “Hotel Yorba,” “Cannon,” “Icky Thump,” We’re Going to Be Friends,” and “The Same Boy You’ve Always Known”), a lone song from the Raconteurs (“Top Yourself”), and a sampling of his solo work (including “Entitlement,” “Blunderbuss,” “Would You Fight for My Love?,” “Three Women,” and “The Rose With the Broken Neck”).

Most intriguing, though, were the covers, which likely motivated Whites plea to discount the notion of authenticity. He played a blistering version of Son House’s “Death Letter,” marked by screaming guitar breaks featuring multi-string bends executed without regard to any conception of key signature, and an equally shambolic and powerful rendition of Blind Willie Johnson’s “John the Revelator.” In the same vein, he covered “Hear My Train a Comin’” with enough feedback to please its composer, Jim Hendrix. But, he also dropped his Fender Telecaster, literally, on occasion, and picked up a 1920s Gibson acoustic to launch into quiet, beautiful, though not pristine, performances like “I Can Tell That We’re Going to be Friends.”

And, well, it was mesmerizing. More performance art than musical performance, a Jack White concert grabs you by the throat and demands your attention. By teetering on the brink of implosion, White draws the audience in, whether out of voyeuristic impulse or beguilement.

Though he may not be authentic, Jack White certainly is original.

Despite his protestations, though, White did verge on folk authenticity for his encore. Having played for an hour and a half of an allotted hour and fifteen minutes, he warned the concert goers that the organizers were threatening to pull the plug. “So,” he advised, “this may be a real folk music,” as he began strumming his old Gibson and leading a group of the day’s performers in that Leadbelly nugget, “Goodnight, Irene.” Sheesh, experiencing a Pete Seeger moment, he even implored, “It sure would be nice if we all could sing along with this one.” We did. So moved was White that he choked up on a few lyrics and shed a few tears.

All that is Not Yacht Rock

“What’s the f@&%ing chance that Michael McDonald is on one of those boats?” asks Ryan Adams. “He probably f@&%ing is. Did any of you see him today?”

Friday’s headliner Adams was mid-set when he slipped into an existential Yacht Rock moment that he began by musing about his yachtness and concluded with a respectable if disdainful and very funny parody of a McDonald-era Doobie Brothers song. “That’s the stuff that you really like, I know,” he added. “Thanks for letting me shine for that one short moment.”

So, if we don’t know what folk music is, we at least, suggested Adams, should know what it isn’t: anything resembling that late 1970s/early 1980s soft rock of California typified by the likes of the Doobie Brothers, Steely Dan, Toto, Christopher Cross, Kenny Loggins, and Boz Scaggs. Can I get an “amen”?

This soliloquy typified Adams’s occasional banter through his hour and a quarter set: pointed, barbed, and quite funny. His yacht reverie highlighted the aesthetic and cultural tension signified by the Newport Folk Festival. The spot at the center of the musical universe dedicated egalitarianism is also where the 1% gather to bask in one another’s material glory. On a lovely, cloudless August day, people anchored their million dollar yachts close enough to the shore of Fort Adams Park to hear the music and avoid the $100 ticket price. Even Ryan Adams, though, conceded that the vision was, if a bit jarring, idyllic: “But, I’ll admit that it is damn pretty here.”

And the music was damned good. Ryan opened with a blazing “Gimme Something Good,” from his upcoming eponymous album, Ryan Adams. With spare backing by his band, the performance was raw, raucous, and compelling. The band was tight and obviously well-rehearsed. They also clearly knew who the boss was, giving Adams space to solo and leaving all the talk to their leader.

Adams stayed in electric mode through the first half dozen or so songs in the set, which included “Magick” from his 2008 album with the Cardinals, Cardinology, “Stay With Me,” another song from the new album, and what Adams described as an oldie –”I mean it’s an oldie where I come from,” “Fix It,” also from Cardinology.

When Adams did put down the electric guitar to don his acoustic and a rack harmonica, the crowd, revealing that it was, indeed, Yacht Rock averse, cheered wildly. Adams, apparently displeased with open acceptance responded, “But, you don’t know what I’m going to play. What if it’s like the worst version of ‘Let It Be’ ever?” He then played what we all hope was the worst version of that song possible. But, after weirdly proclaiming, “I am so inspired by my own self right now,” Adams did reward us with a gorgeous rendition of “Sweet Carolina.”

Adams slipped in “Wrecking Ball,” another tune from what seems a promising new album, and an effective and affecting cover of Danzig’s “Mother,” before closing with “Come Pick Me Up,” from his first solo album, Heartbreaker. Adams’s seemingly heartfelt delivery of the barbed lyrics – “I wish you would come pick me up , take me out, f&ck me up, steal my records, screw all my friends” – served as a fitting end to a great set of music delivered sardonically by a gifted composer and performer.

Reggae, Blues, Bluegrass, Alt-Country and, Well, Folk Music

“Ah,” but you ask, “What’s beyond the headliners and their guest appearances? Just what did the Prince of Pandemonium perceive as he wandered about the Festival?” Well, during his set, White gave shout-outs to Shovels and Rope, the Milk Carton Kids, and Pokey LaFarge.

Shovels and Rope, the married duo of Cary Ann Hearst and Michael Trent, are purveyors of an infectious amalgam of country, blues, old time, and hoedown music. The two trade off playing guitar and sitting behind a minimalist drum set drumming with one hand and playing a small keyboard with the other. They light up a stage and audience like no other duo.

The Milk Carton Kids look forward and back at the same time, doing an updated version of Simon and Garfunkel’s glorious harmonies accompanied by an instrumental backdrop that harks back to the depression. They pull the audience in with an intricate, intimate performance played a low volume that forces the audience to listen carefully.

LaFarge looks like he’s just stepped from the pages of a Steinbeck novel, an author he cites as an inspiration. He and his crackerjack (sorry – I couldn’t resist the reference) band play an entertaining and virtuosic mixture of swing, early jazz and ragtime. And for an encore, LaFarge appeared solo and fingerpicked his composition “Josephine,” which sounded like an authentic hillbilly interpretation of a Mississippi John Hurt tune. What could be cooler? Or more appropriate to a 21st Century folk festival?

White did, apparently, manage to miss a couple of my favorites of the day. Puss n Boots drew a packed crowd, even before Mavis Staples joined them. Their spare, twangy, country backing leaves plenty of space for gorgeous, haunting harmonies. And when lead guitarist Norah Jones is not channeling Luther Perkins, she does a mean Neil Young impression on “Down by the River.” This was perhaps the only guitar solo of the weekend that yielded a standing ovation, at least for those not already standing.

White also missed one my favorite bands: Houndmouth. They play a raw, syncopated, roots music that caused me to describe them last summer in a review of their Lollapalooza performance as “The Band with attitude.” They’ve only improved since. Matt Myers’s guitar playing has become more stunning and his cohorts, Katie Toupin on keyboards, Zak Appleby on bass, and Shane Cody on drums, seem even more assured. They made such an impression at the 2013 Festival that they were greeted this year with a standing ovation as they took the stage. They earned that ovation by opening with a fiery cover of Funkadelic’s “Can You Get to That?” The band mixed songs from their impressive debut album with what might be even stronger material from the album they’ll soon start recording. And, what other young band can pull off closing with a swaggering, inventive cover of the Stones’ “Loving Cup”?

White was likely preparing for his own set when another of the day’s highlights took place: the appearance of the newly reformed Nickel Creek. The original trio, Chris Thile, Sean Watkins, and Sara Watkins, were joined by bassist Mark Schatz, and mixed material from their earlier recordings with great new songs like “The 21st of May” and “Hayloft” from their recent A Dotted Line. Virtuosity tempered with taste and subtlety. It was a breathtaking performance with instrumental breaks so beautiful that, well, you’d want to hold your breath so as not to miss a note.

Jimmy Cliff’s music occupied the other pole of the danceability scale. Backed by an incredibly tight ten-piece band, he spun, stomped, and mimed his way through classics like “The Harder They Come” and “Many Rivers to Cross.” But, he delighted his audience most a funkified cover of cover of Cat Stevens’s “Wild World.”

Devil Makes Three is my favorite, new discovery. This folk/punk/country power trio of Cooper McBean on Guitar and banjo, Lucia Turino on upright bass, and Pete Bernhard on guitar and lead vocals mixes compelling originals like “Graveyard” and “Do Wrong Right” with inventive covers of songs like Doc Watson’s “Walk on Boy” and “St. James Infirmary.” The latter, which included a guest appearance on fiddle by Morgan Eve of Brown Bird, was particularly effective. Starting as a slow dirge, an up-tempo, early jazz arrangement with the power of punk emerged to the delight of the audience.

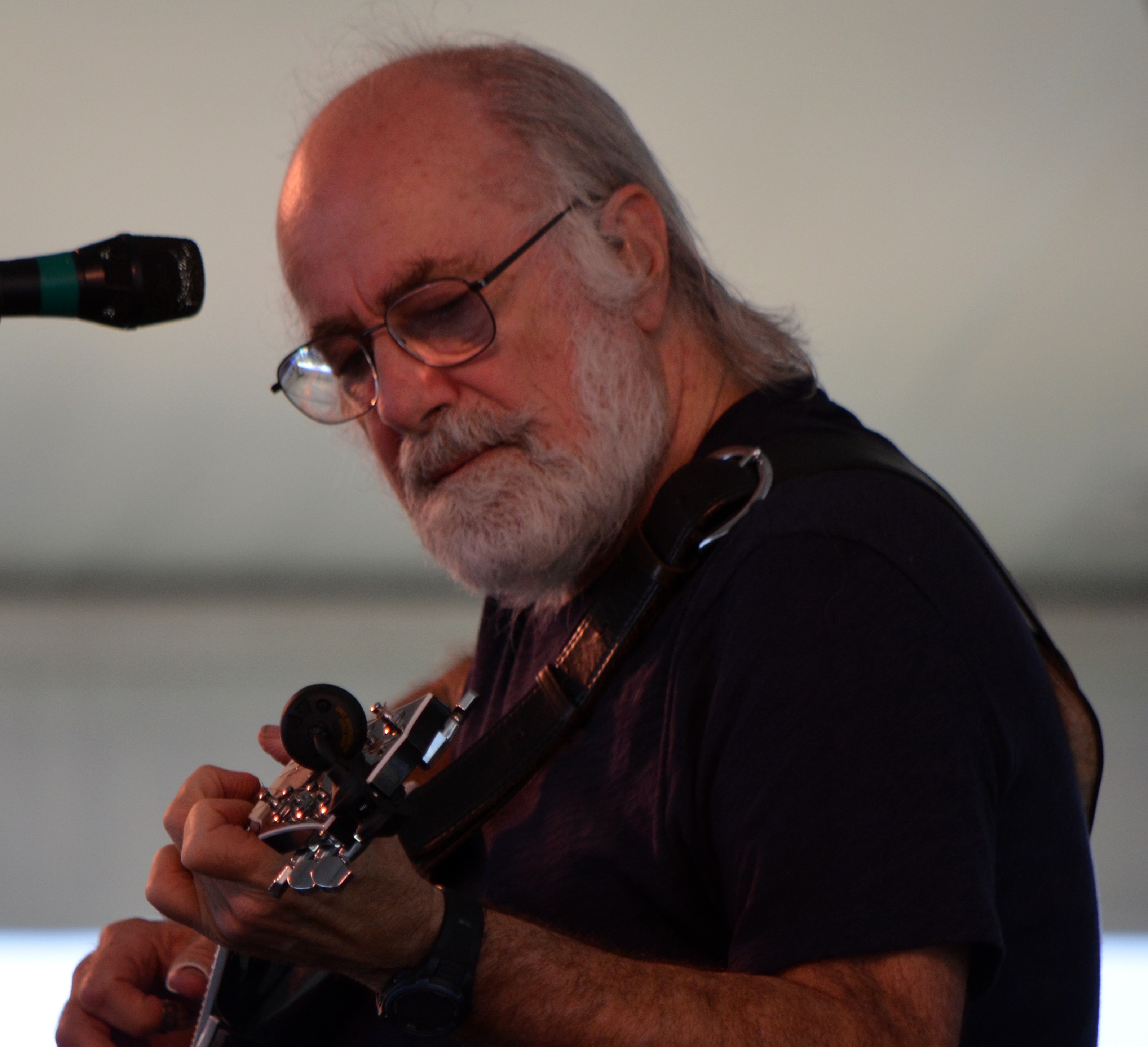

Speaking of the delighted, Robert Hunter, lyricist for many a Grateful Dead tune, brought joy to the tie-dyed crowd. Hunter told the back story to songs like “Sugaree,” “Friend of the Devil,” “Touch of Grey,” and “Ripple.” Driven by economics to return to performing – “I’ve got medical bills to pay, so I’m a working man again” – Hunter strums an acoustic while singing in a voice reminiscent of Jerry Garcia’s. Those spinning and swaying to the music don’t seem to care much that he doesn’t play the guitar like Jerry did.

To quote from “Scarlet Begonias,” another song that Hunter performed, “Once in a while you get shown the light, in the strangest of places if you look at it right.” Whether the Newport Folk Festival is a strange place may be a matter of aesthetic preference, but there’s little doubt that it shines a light on some of the finest and most diverse music being made today.

Well, Maybe a Bit of Authenticity

I suspect that even Jack White, after wiping the tears from his eyes and straightening his hat, would have conceded that the Festival’s closing performance was undoubtedly authentic, at least to the memory of festival gone by and to one of the most powerful of its advocates. After a memorable hour of music, Mavis Staples called to the stage the other performers of the day and, dedicating the song to Pete Seeger, launched into a slow take on “We Shall Overcome.”

Mr. White would have felt at home; there wasn’t a dry eye, on land or sea.

(All photos by Grace Thomas)

Nickel Creek

Puss n Boots

Jimmy Cliff

Robert Hunter

Devil Makes Three

Ryan Adams