Drummer Steve Jordan counts off and the band launches into a slow blues dirge with guitarists Eric Clapton and Gary Clark, Jr. producing a mesmerizing counterpoint by trading biting, vibrato-laden licks. From the wings strolls Keith Richards, bedecked in black suit with long, green scarf, matching, green fedora, and sunglasses. Richards looks up into the floodlights, removes his sunglasses and pockets them, slowly bows to the ecstatic crowd, steps up to the microphone, and talk-sings the classic spoken introduction to Howlin’ Wolf’s Going Down Slow:

Man … You know I have enjoyed things that kings and queens will never have

In fact kings and queens can never get.

And they don’t even know about it

And good times? Mmmmmmmmm-mmh!

Richards then sings the verse, which concludes with “Oh my health is fadin’ on me, oh yes I’m goin’ down slow,” and he turns his back to the audience and saunters over to lean on the piano where Barrelhouse Chuck Goering is pounding out some Otis Spann-style Chicago blues. Clapton, standing back against a row of amplifiers and out of the spotlight, bends into a screaming high note that introduces a long, legato solo. He weaves in and around the beat, teasing emotion from his Stratocaster, doing what, well, he does best. After three choruses, he yields to Clark, who, hunching over his Gibson, coaxes from it a solo filled with strangled, piercing, staccato notes.

Clark is a new discovery for me tonight and I’m spellbound by his performance. He’s got a quiet, confident stage demeanor and a guitar style that somehow melds the primitive with the sophisticated. It’s apparent why he got the nod to stand alongside Clapton to back Richards: he’s the perfect tribute to the man of the hour.

The man of the hour is Hubert Sumlin, who served as Howlin’ Wolf’s guitarist from 1955 through Wolf’s death in 1976. If you want to know why the stars have aligned here tonight on the stage of Harlem’s Apollo Theater, check out the Wolf’s first two albums, “Moanin’ at Midnight” and “the rocking chair album” (his eponymous, best loved second album known to aficionados for its cover photograph). You’ll hear classic Wolfian tunes like Smokestack Lightnin’, Evil, Spoonful, Going Down Slow, How Many More Years, and Wang, Dang, Doodle. In fact, you’ll get 90% of tonight’s set list from those two, classic exemplars of early Chicago blues. Each tune isdefined as much by Sumlin’s angular, idiosyncratic guitar fills as by Wolf’s huge, menacing voice.

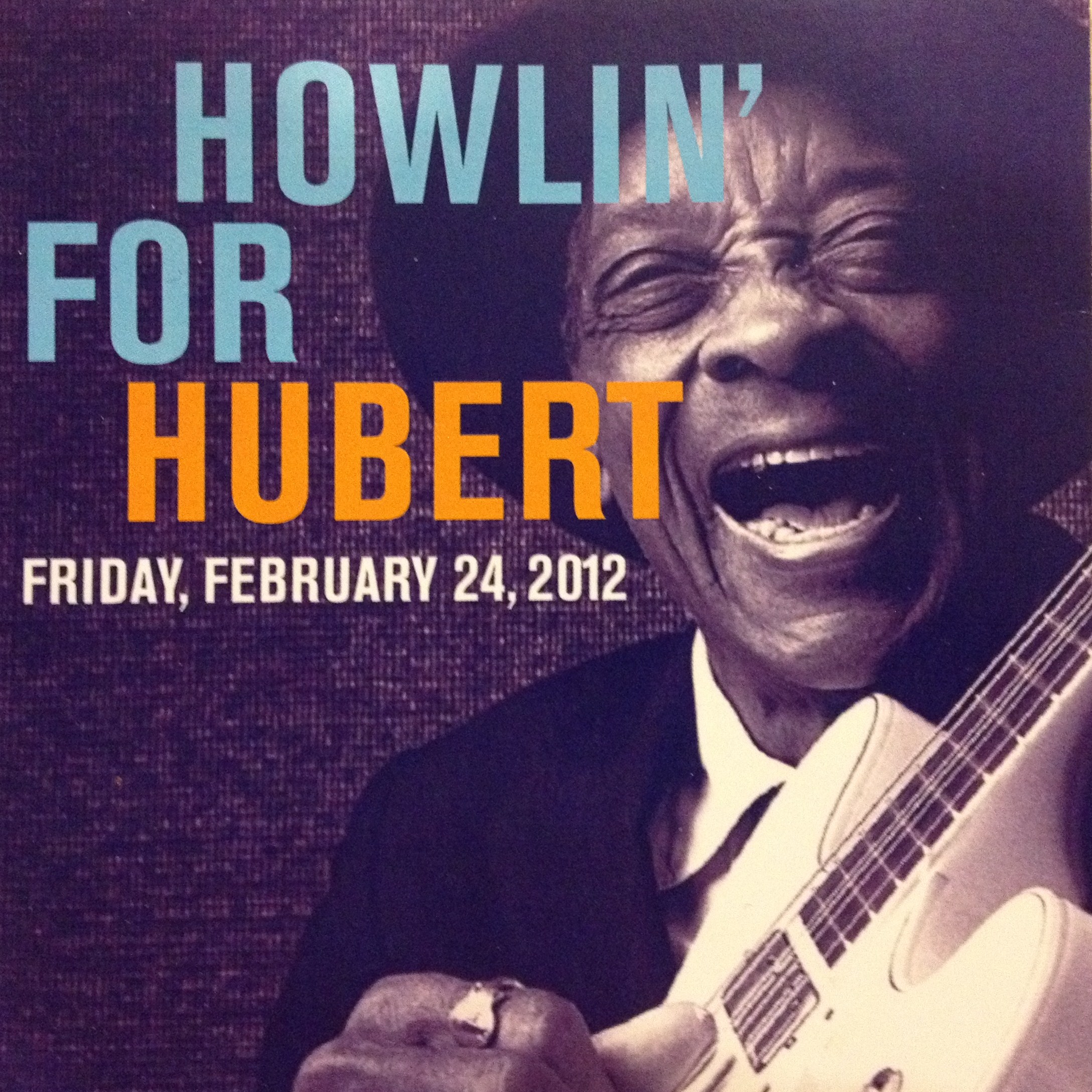

Tonight was intended to be Sumlin’s 80th birthday celebration. Sadly, he died last December. So, “Howlin’ for Hubert” morphed into an event “Celebrating the Musical Legacy of Hubert Sumlin.” The occasion is a Benefit for the Jazz Foundation of America, which supports struggling jazz and blues musicians by providing living expenses, health care, and housing. Sumlin is a case in point. He died destitute, without health care insurance, and spent the last decade of his life living in his manager’s home.

The scene with Richards, Clapton, and Clark encapsulates nearly every aspect of what has been an extraordinary evening. There’s poignancy to Richards’s performance, which he reinforces when, in the face of enthusiastic applause (which he clearly relishes), he intones, ‘Let’s not forget that we’re all here tonight for Hubert.” His performance is humorous, certainly fun, and it’s backed by stellar musicianship. Richards’s few moments in the floodlights are also deliciously ironic. When Wolf sang, “I am not a millionaire,” he uttered the truth. But, for Richards, of course, the line verges on the satirical. Though, as he cataloged in his recent biography, he, like the Wolf, came from humble beginnings, Richards is now a very wealthy man.

That irony suffuses the evening’s festivities. Though we’re in the center of Harlem and celebrating an art form invented by African Americans, the audience is nearly all White. Moreover, that audience, at least according to my very unscientific polling, is uninformed of both tonight’s honoree and the music that he played. As I await the start of the concert, I ask all those sitting within earshot whether they are familiar with Sumlin’s guitar playing. None are. Similarly, no one can identify the musician (Son House) whose recordings are playing through the house PA.

These facts, though, may make the evening’s mission all that more successful. Not only will it raise some serious cash (ticket prices range from $150 to $1,000) for the Foundation cause, but it will bring Sumlin’s music to a new audience.

The organizers appear well aware of the necessity of educating us. The evening commences with a short, biographical video of Sumlin in which he talks of his roots in the Mississippi Delta and of his journey north to Chicago, where he met Wolf. The video contains testimonials of some of tonight’s musicians, a video clip of Sumlin’s recording session with Levon Helm, and Sumlin’s frequent utterance of his favorite phrase, “You know what I’m talkin’ about!”

When the video stops and the projector screen raises, Eric Clapton and James Cotton amble on stage with, respectively, acoustic guitar and harmonica in hand, and launch into Key to the Highway. It’s a great tune with which to open the show. Written by Chas Segar and Big Bill Broonzy around 1940, it became a Chicago blues staple and, more importantly for tonight’s concert, was perhaps most famously covered by Clapton during his Derek and the Dominos days. As a result, it’s a perfect vehicle for drawing this crowd into the evening’s musical genre. The performance also sets an ideal tone. Clapton has chosen an acoustic guitar so that veteran James Cotton’s harmonica can be easily heard and he avoids any flashy soloing so that the spotlight rightly rests on the man who played with Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, and other blues luminaries.

That opening number is followed by a couple of solo outings, the most memorable of which is Jimmie Vaughan’s update of Six Strings Down, the tune he wrote to commemorate his brother Stevie Ray’s death in 1990. Tonight’s version contains a new verse: “I see Howlin’ Wolf holding out his hand saying, ‘I’ve been waiting for you Hubert. Welcome to the band.’”

When Vaughan exits, the band takes the stage, and quite a band it is. Sometimes, too much tribute can be too much of a good thing. Drummers Steve Jordan and Jim Keltner will spend the evening locking eyes and attempting to stay out of one another’s way, but a simple twelve bar blues cannot always accommodate two drummers, no matter how legendary they are. Fortunately, upright bassist Larry Taylor and electric bassist Willie Weeks usually (but not always) do not play on the same tune. But, guitarists Billy Flynn, Eddie Taylor, Jr., and Danny Korchmar cover most of the evening’s offerings with a blanket of rhythm. Organist Ivan Neville and pianist Goering do their best not to trample on one another’s lines. It’s certainly a tribute to Sumlin’s legacy that so many wanted to join the house band. But, it says more about musical director Steve Jordan’s sentimentality than about his artistic vision. Still, it’s a thrill to see so many great players in one band and, uh, interesting to see how the folks doing tonight’s mixing attempt to make it work. But, three rhythm guitarists? Well, OK, at one point during the evening, a fourth slips in.

First to play before the band is the only musical mismatch of the evening. Jody Williams, who began playing with Howlin’ Wolf in 1954 before Sumlin joined them a year later, takes the stage with Kenny Wayne Shepherd in tow. Neither a vocalist, they play an instrumental that sounds a bit like the Otis Rush classic, All Your Loving. As the band starts up, I wait nervously to see whether Williams can still play. Indeed, he can! He plays a beautiful, understated solo that features some of the trademark bends evident on those early Wolf recordings. Next, though, Shepherd takes a solo. He walks to stage center, stomps on an overdrive box and proceeds to play twice as fast and three times as loud as William, all the while mining the rock and roll guitarist book of poses. The audience screams, oblivious to the insensitivity being displayed on stage. Williams, though, seems content and unfazed. He plays another lovely, understated solo.

This really is the only misstep of the evening and I hope that young Shepherd is watching from the wings later when a self-effacing Eric Clapton teams with Williams to perform Forty-Four Blues. Clapton sings, plays the signature rhythm riff, and lets Williams take the guitar solo (and also hands out solos to pianist Goering and a harmonica player Kim Wilson).

Clapton’s deference provides for a beautiful moment among many tonight. One of the most memorable transpires when two former members of Wolf’s band, pianist Henry Gray and saxophonist Eddie Shaw, perform Sittin’ on Top of the World. Shaw has a huge voice that suits this bit of sarcasm perfectly and he and Gray take great solos.

Gray stays for the next performer, Elvis Costello, and while Costello plugs in his big, Gibson archtop, Gray lapses into a beautiful, impromptu boogie woogie. Costello steps to the microphone and asks the question that is on many minds: “What in the hell am I doing up here?” It turns out that not long before his death, Sumlin sat in with Costello and the Impostors. In tribute, Costello performs a fun and funny Hidden Charms.

Costello is a crowd pleaser, but not nearly so much as ZZ Top’s Bill Gibbons. With a Telecaster slung low, he growls out I Asked for Water (but She Gave Me Gasoline). Clapton has said that Gibbons has an encyclopedic knowledge of blues and he proves it here. After letting Warren Haynes play a perfectly nasty slide solo, Gibbons slays with a few well placed, piercing notes.

Other highlights from the four and a half hour concert include Susan Tedeschi wailing the vocals and trading solos with husband Derek Trucks on Rolling and Tumbling and Three Hundred Pounds of Heavenly Joy. Buddy Guy pleases the audience with histrionics during Hoochi Coochie Man and by hamming it up with blues shouter Shemekia Copeland on a slow, scorching version of James Cotton’s Baby Please.

The evening’s best performance may be that of Gary Clark, Jr. As Clark takes the stage, all the band members except drummer Steve Jordan and bassist Willie Weeks depart. Stalking the stage slowly and coolly, he fingerpicks a funky Catfish Blues, tossing in prickly fills and a monstrous solo. Clapton joins Clark and the stripped down band for Down in the Bottom and then Clapton plays Little Baby with Kim Wilson.

Clapton then brings Keith Richards up for his dramatic turn at Going down Slow and leaves the stage as Richards, on acoustic slide guitar, and James Cotton perform a Howlin’ Wolf tune that has stayed in the repertoire of the Rolling Stones for decades, Little Red Rooster. Richards is, as Tom Waits once observed, pure theater. He’s sitting on a folding chair, hunched over his guitar, and seems as if he is unaware of the audience. He plays sparingly and when he hits open strings on his guitar, his left hand slowly floats up toward the ceiling, somehow making it back in time for the next slide lick. Cotton seems in his element and he solos generously.

The next song brings us back to where we started. Someone hands Richards an electric guitar and he and Clapton slowly work into Spoonful, another tune from Clapton’s portfolio, this one from his days with Cream. Richards croaks the vocals while Clapton, still standing as far from the spotlight as possible, plays barbed fills and leaves most of the soloing to James Cotton. Richards puts a hand to his heart, offers a subtle bow to the crowd, and walks off stage.

It’s now time for the finale and all, including Richards, return to the stage as Clapton and band cue up Wang Dang Doodle. It’s a fun, loose production led by Shemekia Copeland and, charmingly, tonight’s big guns shun the spotlight, preferring to blend in with the throng. Clapton laughs and chats with Warren Haynes, Susan Tedeschi, and Derek Trucks. Billy Gibbons stands mid crowd, drawing attention to himself only when he pulls out a handkerchief to fan Kim Wilson during a typical-for-him hot solo. Richards just stands in the crowd, occasionally picking his guitar and smiling from ear to ear.

The night ends when Steve Jordan announces that the group will perform the song that contains Sumlin’s “best known lick,” Smokestack Lightning. It’s a one chord dirge that highlights that syncopated lick that now lies at the heart of the electric blues lexicon. As the 19 (!) guitarists bring the song to a stuttering end, all exit, the musicians toward back stage and we audience members to the Harlem night.

Well, almost everyone exits. Henry Gray has been standing among the guitarists. When he spots the now-free piano, he sits down and starts up a boogie woogie. Pushing 90 years old and a fixture of Chicago blues since he was a teen, it’s as though he wants us to know that the blues don’t fade when one of its messengers succumbs to mortality.

“You know what I’m talkin’ about!”

(Alas, the concert’s promoter, Live Nation, did not allow photographs.)