I walk up a flight of stairs and enter the huge room, still cold from Chicago’s February air. Before I can take off my coat and get my recorder running, Nels Cline–avant-garde hero, Wilco powerhouse guitarist and Jazzmaster icon–already wants to show me something. It’s not the beat-to-heck ’59 Fender he’s known for playing; it’s not the Barney Kessel model that Wilco frontman Jeff Tweedy favors or Cline’s new signature-model Tim Schroeder amp. In all honestly, I’m not quite sure what it is.

“I want to direct your attention to one of the most incredible guitars ever in the history of mankind,” he exclaims as we stand amid what must be at least 100 guitars. Cline, one of the fiercest electric players around, proceeds to pick up a classical guitar made by Hopf, the oddball European guitar manufacturer. But this isn’t your typical nylon-stringed classical guitar–it’s a six-string classical bass guitar. I’m a tad speechless, having seen most everything of the fretted-instrument variety. Cline, who has also seen his fair share of guitars, says, “It’s one of the most amazing things I’ve ever seen in my life–and it plays completely in tune!”

I’m left muttering the obvious question.

“Does someone actually make strings for six-string classical bass guitars?”

“Piano strings,” loft manager Jason Tobias shouts matter-of-factly from his desk across the room.

Such is life at the Wilco loft, the acclaimed indie-rock band’s filled-to-the-brim rehearsal, storage and sometime recording space where eccentric vintage instruments sit side by side with near classics, where a spotless Studer 24-track tape deck is always on standby for a new tune and where gear talk can get pretty geeky. I try to imagine what Tobias’ typical workday must be like: make sure amps and guitars are serviced; keep a running inventory of the dozens of boutique pedals floating around the place; order new flight cases for the Mellotron’s tapes; and, at least now and then, procure a batch of piano strings and figure out which will work in a pinch on a six-string classical bass. Nice work, if you can get it.

That wouldn’t be the last Hopf guitar I’d see during my visit to the loft, nor would it be the only time I am left a little speechless. If Wilco wanted to start a music-based commune, they’d be off to a pretty good start. Four bunk beds are scattered about so that the Los Angeles-based Cline and other band members have a place to crash. Personal effects–Devo helmets, Nudie suits, autographed head shots from comedy legends–adorn every free space, and there’s, of course, a stocked kitchen. The loft doesn’t feel like a rehearsal space so much as Wilco’s version of the Batcave.

The band occupies the entire floor of the building. Drum booth aside, they don’t use walls to divide up the space, just heavy-duty industrial-grade shelves filled to the ceiling with guitar cases and amps. Everywhere you look, there are instruments. The aforementioned Mellotron Mk VIII sits near the middle of the space, a fresh take on the classic, complicated keyboard from Sweden’s Markus Resch. I get a quick demonstration from the band’s keyboardist (and occasional guitarist), Pat Sansone. As he removes one bank of tapes from the bowels of the console, I find myself at a loss once again. And here I thought harp guitars were complicated affairs!

Though Cline has been crashing here for weeks, he’s cheerfully running around and showing me stuff like he’s a first-time visitor. He picks up a near-mint Vox Guitar Organ, shows me the wall lined with several color-coordinated Jerry Jones-built Danelectro reissues and points to the original Supro practice amp, now semi-retired, that Tweedy used on so many Wilco recordings. Every piece of gear or memento, it seems, has a story. I can’t think of too many bands that so equally covet so many kinds of gear; at Wilco’s loft, vintage Martin and Gibson flattops sit alongside Carr amps and rare, small-shop distortion boxes.

Beyond his stellar playing and his love of Jazzmasters, Cline is best known for his exotic effects pedals. As we examine his cluttered pedal board, my eyes are drawn to a stomp box covered in fake purple fur.

“Henry Kaiser turned me on to that,” he says, referring to the pedal that looks a bit like a flattened Furby. “The Ugly Face. It’s made by an art professor in San Francisco. It’s one of the most extreme, bizarre, wonderful fuzz boxes ever. Henry’s turned me on to some good pedals in his day; he’s the guy who first showed me the [Klon] Centaur Overdrive, which is one of my main things, and he was the first guy to show me the [Z.Vex] Fuzz Factory, which is another one that I use.”

Cline still remembers his first visit to the loft, back in 2000 or 2001, when he came by to–what else?–borrow some gear. “I first met Jeff Tweedy when the Geraldine Fibbers, the band I used to play in, was opening for Golden Smog. And then Carla Bozulich, from the Fibbers, and I were doing our duo called Scarnella, and Greg Bandy and I were doing Interstellar Space Revisited the same night at [Chicago club] the Empty Bottle. I needed an amp and a baritone guitar. Jeff, through Carla, loaned me what, at that time, turned out to be a huge, twin-reverb-sized Matchless and a Danelectro baritone guitar. I came here in a cab; I just remember coming in and screaming, ‘Whoa.’”

The giant collection of gear at the loft is a testament both to Wilco’s success as a band and to Jeff Tweedy’s success as a guitar and gear hound. With each new record, Wilco becomes tougher to pigeonhole; they meticulously craft dense layers of pop, rock, country and noise, and once you witness all the gear they’ve accumulated, you start to understand why–and how. This is a band that has instruments of every variety at their disposal at all times, and it seems they all get used at least once in a while.

The day I visit, a new addition arrives. The band had been recording tracks for their new album, Wilco (the album), with a skeleton crew in New Zealand at Neil Finn’s studio, and while down there Tweedy became infatuated with Finn’s Gibson J-185. It’s the acoustic guitar heard all over the new recording, so Tweedy set out to purchase one for himself.

When someone arrives with Tweedy’s newly acquired ’52 Gibson–fresh from the shop of luthier Frank Montuoro, where it received some needed TLC–it quickly becomes the office water cooler. It had loose braces, among other issues, pre-repair, but everyone agrees that the guitar has turned out great. Still, the murmur is that Tweedy isn’t going to be too happy when he gets it.

“Those strings are way too lively for Jeff,” Sansone states.

In comes Tweedy, running late and suffering from a cold. When he finally enters, the first words out of his mouth are, “You know I’m sick when I don’t show up two hours early for an opportunity to talk about my guitars!”

Then, sure enough, he grabs the J-185, inspects the repairs, fingerpicks a Fahey-style tune (quite well, I should add) and, almost on cue, says, “I like it, but I won’t like it completely until these strings are completely dead. I hate new strings.”

You hate new strings, I ask? “It doesn’t sound like a record,” he says. “I must have never had a record player that had any high end, I’m thinking. What I want to hear is never that crispy.” Tweedy hands the guitar to Cline for further break-in and takes over as tour guide.

The band has been renting the loft for almost a decade; Tweedy stumbled on it when his wife’s friend was looking for rehearsal space. “He just had like a bar band,” Tweedy remembers, “and he came up and he saw this place and he really, really loved it, but he couldn’t afford it. He told my wife about it and said, ‘You should have Jeff go look at it, because somebody should have it.’ So we did, and we’ve been here longer than I think anybody else in this building.”

Tweedy will be the first to admit that his loft stash is all over the musical map. “There’s no real focus to my collection, other than things that make me happy and things that feel inspiring to me,” he says. “And, I guess, in some cases, it’s stuff where I have some sort of hero emulation; I just have to have a guitar because I saw so-and-so play it. I have a thing for Dylan guitars–a [Gibson] Nick Lucas would have been one I bought for that reason, and the Martin 00-21NY I think I bought for that same reason.”

Soon, we stop at a Gibson J-45 that appears to have the band’s name inlayed into the fretboard. “This is the first nice acoustic guitar that I ever owned,” Tweedy interjects. He’s had it since the early ‘90s. “When we made AM, the guy that was doing the photography for the record was like, ‘I really want to get a guitar that has the country-style inlays, where it says W-I-L-C-O.’” Tweedy agreed and the next day found his beloved guitar covered with a bunch of vinyl adhesive stickers, spelling out “Wilco.”

“I was like, ‘Whoa, I wouldn’t have put stickers on my guitar, but OK.’” The stickers have endured, and the J-45 guitar has even graced the cover of No Depression magazine. Nearby, past the autographed photos of Bob Newhart and Don Rickles, there’s yet another Hopf, this one an Art Deco-inspired archtop. Tweedy points to a picture high up on the far wall featuring Elvis, in the Army, toting pretty much the same model Hopf. “It’s on ‘How to Fight Loneliness’ and ‘In a Future Age,’” Tweedy says. “It’s a really good guitar to bow because the neck radius has a little bit of an arch to it–you can hit individual strings with the bow.

“For some odd reason I keep finding Hopfs,” Tweedy laughs. “I keep showing them to Nels, and lately he keeps buying them. It saves me a lot of money.” (Later that day, Cline indeed shows me an electric Hopf on Gbase that was pointed out by Tweedy.)

Onstage, Tweedy is often seen playing a slightly more coveted guitar, one of his Gibson Barney Kessels. “I had gone into a guitar store with my wife,” he remembers of his first Kessel model, “which is a very rare occurrence. She thought that it was a really beautiful guitar, and I told her that I always wanted one. A couple of months later, just out of the blue, she had bought it for me. And that one is completely mint, perfect, with hang tags still on it. So I hardly ever play that one.

“Coincidentally, I found one that was more of a player, and that’s the main one I use. Since then, I found another one that’s pretty beat that I’ve had work done on and I can make that one work onstage. And then I have a black one that I think has got to be pretty rare–it’s a factory-finish black one.” Tweedy is also not immune to buying amps. The low-watt Supro amp was a favorite for many years, but has since been retired. “Tim Schroeder took it apart and measured everything that there is to measure and built an exact reproduction of it,” Tweedy says. “And it’s really great. That’s what I’m using now, and it’s really comparable.” He’s often spotted playing through one or two Vox AC30s at shows as well.

“My collection has a mind of its own,” he adds. “It continues to grow. I’m compelled to buy guitars and luckily I’m in a position where I can afford to buy guitars periodically. But to be honest, I don’t have a real strict philosophy to my collecting.”

I ask Tweedy if it’s ever overwhelming being at the loft, with all of the gear choices. “I can’t help but think,” he says, “that maybe not having all of this stuff in New Zealand–only being able to borrow guitars from people and having a couple of my own guitars there–might have contributed to being a little bit more focused.

“I hate to admit that,” he laughs, “because that would imply that I should get rid of all of this.”

In a sense, each Wilco album for the last decade has been graced by another instrument–beyond the Schroeder amps, the strange pedals and the vintage Fenders: the loft itself. As it happens, Wilco, just like a lot of us, has loud neighbors.

“There’s a lot of noise coming from the other floors, and there always has been,” Tweedy says. “There are a lot of extraneous performances on our records that we’ve recorded here, including the one we just finished. There’s a lot of drill-press sounds on this record; we always tend to keep them. There are also nearby cell-phone towers, so there’s a lot of RF interference all over the last records. This record we finished is the first where we turned it up and made it a part of the record.

“We’re hoping for a Drill Press Grammy,” Tweedy concludes. “And the best performance in a baroque pop song by a drill press goes to… whoever the guy is who works upstairs.”

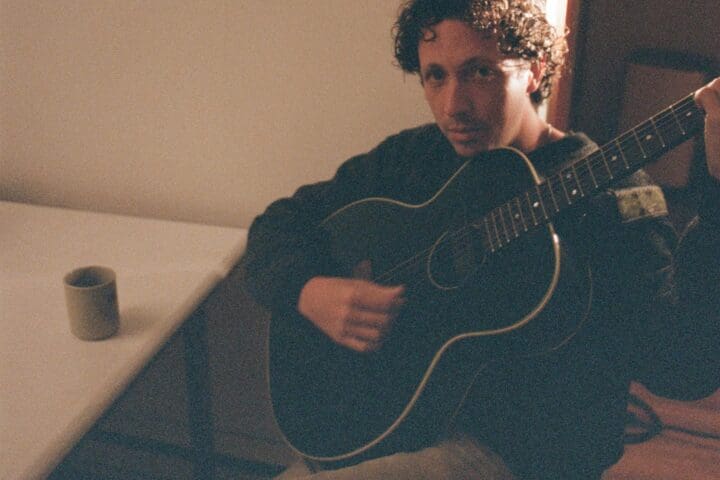

Jeff Tweedy